Though lighthouses have captured much of the glory when it comes to seacoasts, shorelines and shipwrecks, their usefulness quickly fades when thick mists and pea-soup fogs roll in. At times like these, lighthouses hand the torch to their less glamorous but no less essential aural counterparts: foghorns. And to that we say, “Hear here!”

Shore Sounds Good!

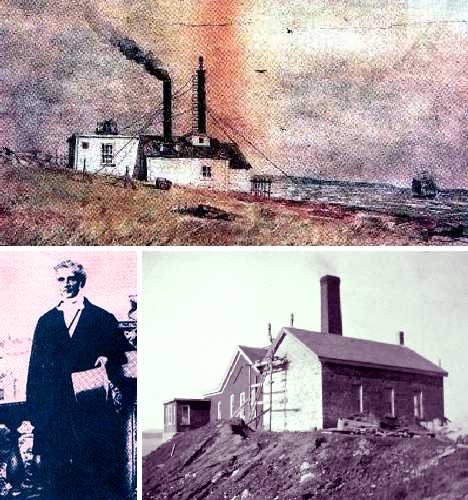

(images via: New-Brunswick.net and Lighthouse Friends)

(images via: New-Brunswick.net and Lighthouse Friends)

Foghorns have been sounding off since 1859 when a steam-powered “fog alarm” invented by Robert Foulis began operations on Partridge Island, New Brunswick, Canada. In one form or another, the Partridge Island foghorn (shown above in a watercolor sketch from 1865) continued to sound out a mournful moan to wayward mariners for 139 years, until it was finally switched off on May 4th, 1998.

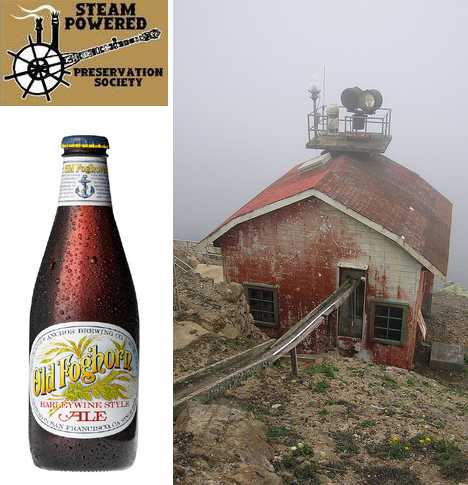

(images via: SPPS, BSmif and Anchor Brewing)

(images via: SPPS, BSmif and Anchor Brewing)

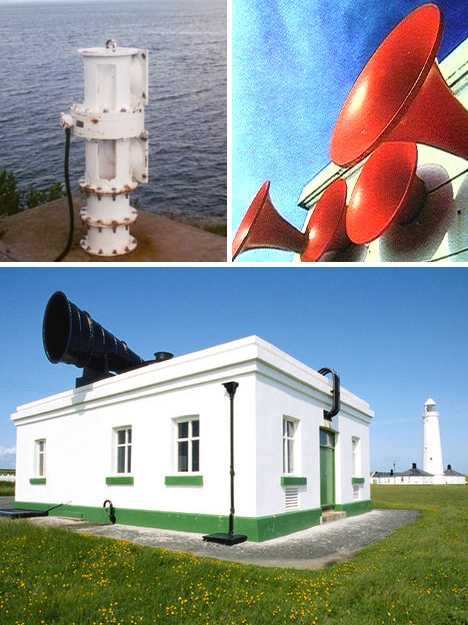

Robert Foulis supposedly got the idea for a low-frequency fog alarm one misty night while listening to his daughter play the piano. He noticed something curious: the lower notes carried further and sounded louder than the higher notes. Foulis’ first fog alarm not only blasted out loud low tones, it was automated and could be set up to play different coded cadences so that sailors could determine which location they were nearing. Most steam-powered foghorns use coal to heat their boilers. You can see the incoming coal chute (above right) leading down into the boiler building of the Point Reyes foghorn.

Foghorns Of Plenty

22

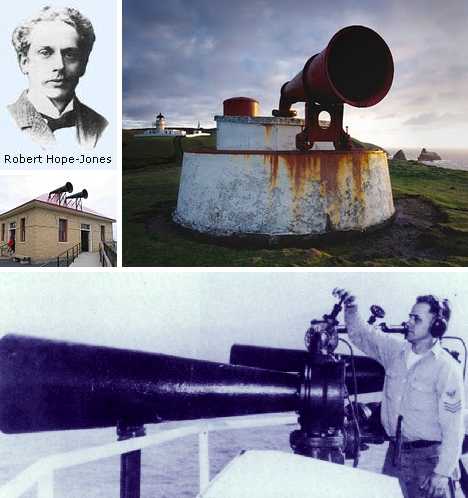

(images via: Terry Pepper, Night Whispers, Kosmix and Wikipedia)

(images via: Terry Pepper, Night Whispers, Kosmix and Wikipedia)

The next technological leap in foghorn design came in the late 1890s when English pipe organ designer Robert Hope-Jones rigged his Wurlitzer organ to produce what he called a “diaphonic” tone. Hope-Jones’ diaphone was further refined by Canadian John Pell Northey, who added a secondary air supply that resulted in the full, rich, two-tone foghorn that remains the benchmark for foghorns over a century later.

Split Rock Music

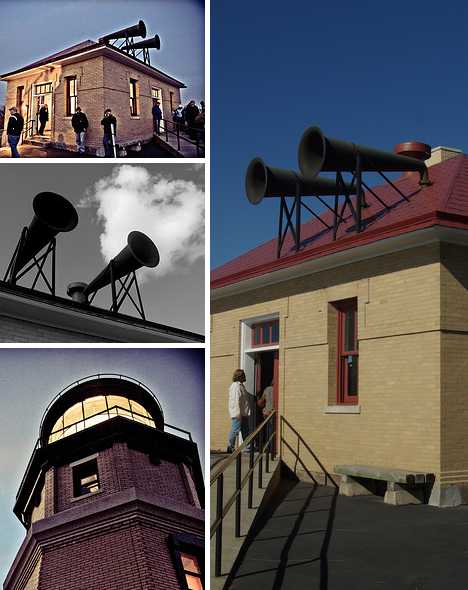

(images via: MBillings_7, PedalFreak and RSH3339)

(images via: MBillings_7, PedalFreak and RSH3339)

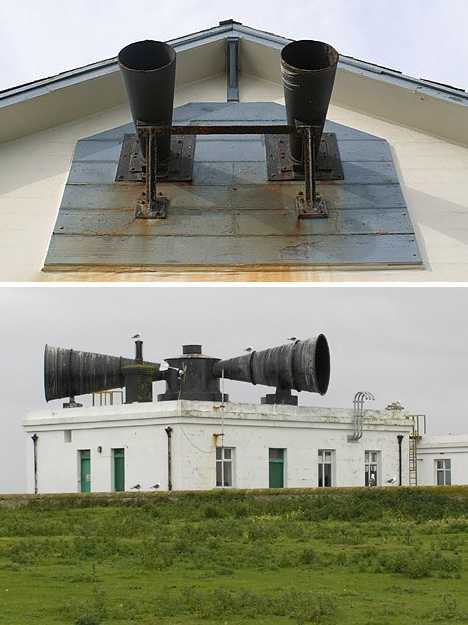

Split Rock Lighthouse has been guarding the north shore of Lake Superior southwest of Silver Bay, Minnesota, since 1910. A pair of diaphone foghorns were mounted on a separate building (above). Originally powered by a gasoline engine and an associated air compressor, the foghorns were switched over to electric power in 1940 and sounded their last blast in 1961.

The Sound Of Silence

(images via: Fair Isle and Manx.net)

(images via: Fair Isle and Manx.net)

What could be lonelier than the sound of a foghorn? How about a silenced foghorn, which are becoming more and more common as time passes. The days when ship captains aboard sailing ships becalmed in mist cupped their ears and listened intently for the call of the foghorn are long gone. Today’s ships hum with the throb of diesel engines and captains fix their positions via radar and GPS systems. Mighty foghorns such as the one above, located on the Langness peninsula on the Isle of Man, are left to the mercy of the wind, rain and corrosive salt spray.

(images via: Neepdocker and Manx.net)

(images via: Neepdocker and Manx.net)

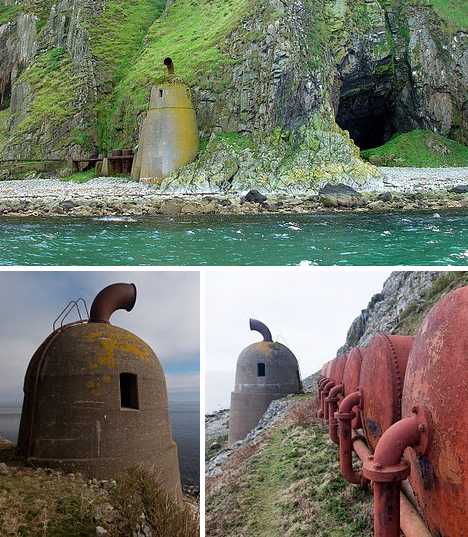

Some of the loneliest and at the same time, most scenically spectacular foghorns are located on the Scottish isle of Ailsa Craig. Now uninhabited and a designated bird sanctuary, Ailsa Craig and its huge foghorns have been silent since 1966.

(images via: Wikipedia, NLB and SeaKayakPhoto)

(images via: Wikipedia, NLB and SeaKayakPhoto)

The massive foghorns located on the island’s north and south coasts were supplied with air from now-rusting compressed air tanks, kept full via now-ruined gasworks. Ailsa Craig was extensively quarried for its unique blue-gray granite, used to make curling stones. Blasting is now forbidden but loose rock is still mined to make the famous Scottish “rocks.”

Still Hear

(images via: Racerocks, James Jegers and BBC Radio)

(images via: Racerocks, James Jegers and BBC Radio)

Though not as common as they once were, there is still a need for foghorns in many parts of the world. As well, technology has given foghorns a new lease on life. Equipped with laser generators and computer operating software, modern marvels like the white beauty (above left) from Maine, USA, shine a beam of light into the mist and should the fog reflect back a significant quantity of light, the electric foghorn will sound.

(image via: Biking Birder 2010)

(image via: Biking Birder 2010)

Modern or not, foghorns’ claim to fame remains their loud and penetrating sound designed to be heard and heeded from many miles away. One hopes the gentleman above, at Scotland’s Mull of Galloway lighthouse’s foghorn, has remembered to wear his earplugs.

You’ll Be Mist

(images via: Indospectrum and Excel Math)

(images via: Indospectrum and Excel Math)

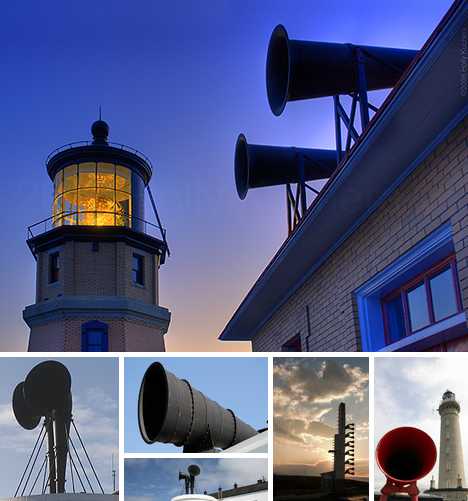

Just as the inclement weather they’re designed to warn against relentless batters them, foghorns seem to endure though some have been silent for many decades. Part of this is due to their isolation: their residual scrap value isn’t worth the time and trouble to retrieve them from islands, points and peninsulas.

(images via: Flickr/Splitrock and Fotolibra)

(images via: Flickr/Splitrock and Fotolibra)

Not that their presence harms anyone or anything – in fact, the evocative nature of foghorns makes them a favored subject for painters and photographers.

(image via: Essex Explorations)

(image via: Essex Explorations)

That a man-made device built to emit sound can appeal to our visual and emotional centers is something worth appreciating… even, if I dare say, worth blowing your horn about.