Construction is a deadly industry. Falls, electrocution, blunt force trauma and mishaps with heavy machinery are just a few of the hazards workers face on project sites around the world, whether they’re building a small house or a massive dam. Historically, it hasn’t just been the nature of the work that makes this job so dangerous, but also attempts to cut costs and boost productivity at the expense of worker safety. Though tighter regulations have made mass worker deaths less common, they still happen, and the numbers can still be shocking.

When we calculate the costs for major infrastructure projects, we rarely include human lives in the figures. How do we do that math, anyway? Bridges, canals, tunnels, dams, railways and highways have made a lot of human “progress” possible over the last two centuries, but it’s worthwhile to consider their true toll – and remember that many of the dead were migrant workers, colonized people and prisoners.

Death and the Dam

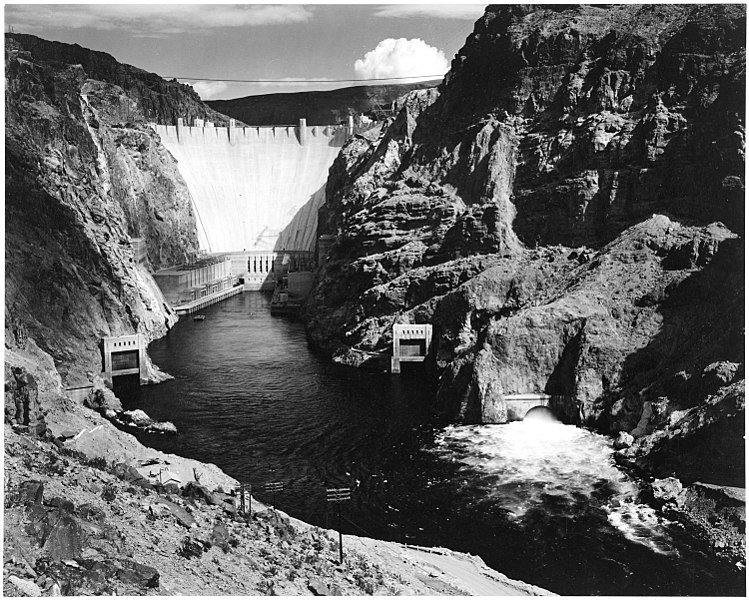

Even putting aside the environmental cost of dams – which have the greatest negative impact on rivers of all human activities – these behemoth structures are wildly expensive, and thousands of lives have been sacrificed to build them. The Hoover Dam, a 1,244-foot-long, 726-foot tall monstrosity on the Colorado River that holds back so much water it actually deformed the Earth’s crust, famously involved over 100 deaths throughout its construction between 1922 and 1935. The first was J.G. Tierney, a surveyor who drowned while looking for an ideal spot, and the last, strangely enough, was Tierney’s own son Patrick, an electrician’s assistant who fell from an intake tower.

In between were at least 100 “industrial fatalities” and dozens of deaths officially attributed to pneumonia but possibly linked to carbon monoxide poisoning. Workers often found themselves using gasoline-powered equipment in poorly ventilated spaces that reached temperatures as high as 140 degrees Fahrenheit. Though legend has it that some of the men are buried in the Hoover Dam, it’s unclear whether there’s any truth to it – unlike a similar situation at Montana’s Fort Peck Dam. When a 1938 structural failure caused 34 workers to become trapped by debris, eight died, and only two bodies were recovered. The other six remain entombed somewhere beneath all that shale, bentonite and concrete.

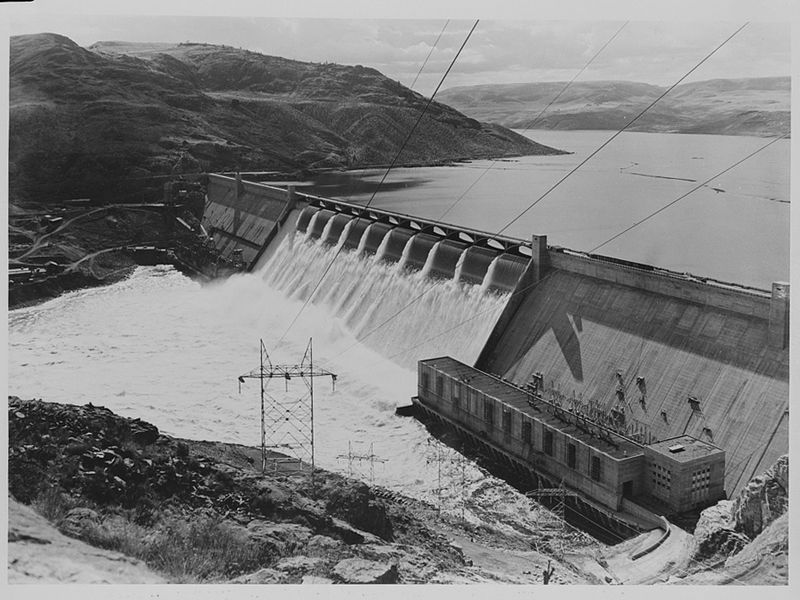

In Washington State, the construction of the Grand Coulee Dam not only damaged crucial salmon runs and flooded the traditional fishing sites, burial grounds and sacred cultural gathering places of the Spokane Tribe without adequate compensation, it resulted in the death of 77 workers between 1933 and 1941 and another four during construction of the Third Powerhouse between 1967 and 1975. As of 2018, there’s no monument or placard honoring any of the lives lost. Other dams along the Columbia, including the Bonneville, The Dalles, the John Day and the McNary, displaced the Native American tribes who lived along the shores of the Columbia River for millennia, leading to generational poverty that makes the true death toll of the dams a lot higher than the official numbers from the time of their construction.

The single deadliest dam remains the Aswan on the Nile River in Egypt, which took over 30,000 workers a decade to complete and resulted in 550 deaths. This didn’t happen at the turn of the 20th century, but rather 1960-70. Though it’s credited with boosting the Egyptian economy, at least 100,000 people had to be relocated, and many priceless archaeological sites were flooded.

Tragic Tunnel Disasters

One of the worst industrial disasters in United States history, the Hawks Nest Tunnel began as a diversion project for the New River in West Virginia. When workers discovered valuable silica in the rock, they were asked to mine it as a byproduct of construction – without any protective gear. All the dust they inhaled led to a disease known as silicosis, a lung disease marked by inflammation and scarring. The official death count is 109, but due to the number of workers who quit in the midst of the project, the number could be as high as 1,000.

New York City’s Third Water Tunnel has been under construction since 1970, and it’s still not complete. The largest capital construction project in New York City history, the tunnel is located more than 500 feet below street level and will ultimately stretch more than 60 miles once the third and fourth sections are finally built. Twenty-four deaths are attributed to the project, mostly consisting of workers, but also including a twelve-year-old boy who fell into an uncapped water pipe in the Bronx.

And, in Switzerland, 19 people died while working on the ten-mile St. Gotthard Road Tunnel, which connects central Switzerland to Milan, Italy through the Alps, with an additional 8 perishing during the construction of the separate 35.5-mile Gotthard Base Tunnel, the world’s longest railway and deepest traffic tunnel.

Treacherous Highways & Railways

Connecting Pakistan and western China through the Himalaya Mountains, the Karakoram Highway is the highest paved road on Earth and passes through the 15,397-foot Khunjerab Pass, the world’s highest border crossing. It’s full of hairpin curves and deadly drop-offs and often gives drivers altitude sickness, making it dangerous to navigate. It was also unsurprisingly arduous to build. 810 Pakistani workers and 82 Chinese workers died due to landslides and falls throughout its 27 years of construction between 1959 and 1986.

Constructing railways is even more treacherous. The First Transcontinental Railroad, a 1,912-mile continuous rail line built between 1863 and 1869 from the eastern U.S. rail network at Omaha, Nebraska to San Francisco made California and the rest of the West Coast of the United States accessible during a time of westward expansion. Americans were free to travel from coast to coast with unprecedented ease, and the railroad enabled the shipment of millions of dollars worth of freight every year. It also had a massive impact on the Native Americans through whose lands the railroad passed, resulting in cultural, economic and human destruction that’s hard to quantify, including the loss of the bison many tribes relied on for survival. The tribes who did attempt to fight back, like the Paiute, were dismissed as saboteurs.

Meanwhile, the manual labor required to produce the railroad was almost entirely carried out by thousands of emigrant workers from China, who received less pay than white workers for difficult and dangerous tasks. The Central Pacific didn’t keep records of worker deaths, but it’s estimated that some 1,200 died. They were temporarily buried along the rail line by fellow workers, the bones collected and shipped back to China at a later date according to Chinese practice.

The Burma-Siam Railway is nicknamed “The Railway of Death” for a reason. Built by the Empire of Japan in 1943 to support its forces in the Burma campaign of World War II, the railroad was completed using the forced labor of up to 250,000 Southeast Asian civilians and 61,000 Allied prisoners of war. Conditions in the jungle were so brutal, with guards beating and torturing workers and not enough food and medicine to go around, that an astonishing 90,000 laborers and 16,000 Allied prisoners died.

The High Cost of Huge Canal Projects

Hailed as one of the greatest infrastructure projects the world has ever seen, the 48-mile Panama Canal required the removal of more than 3.5 billion cubic feet of dirt to connect the Atlantic Ocean with the Pacific Ocean through the Isthmus of Panama, diverting the Chagres River and creating the artificial Gatun Lake. France began the project in 1991, but engineering challenges and a high worker mortality rate brought their efforts to a stop, and the United States took over in 1904. Ten years later, it was open for business.

The Panama Canal is often considered one of the wonders of the modern world, and its annual traffic is estimated to be over 15,000 vessels. A grandiose display of American exceptionalism that helped make the U.S. a major world power, the project forever changed Panama’s culture. But it came at the cost of at least 5,609 lives (likely far more than that, by many historians’ calculations), most of whom were contract workers from the Caribbean.

In 1931, the Soviet Union put 126,000 gulag inmates to work on the White Sea – Baltic Sea Canal, a ship canal running through Russia from the White Sea in the Arctic Ocean to the Baltic Sea in St. Petersburg. The 141-mile route was hailed as a success for its quick construction, completed four months ahead of schedule using almost entirely manual labor, though it ultimately wasn’t as deep as originally planned due to cost issues. Though prison labor projects weren’t usually publicized, the White Sea project was an exception, with the Soviet Union boasting about how the “class enemies” (political prisoners) rehabilitated themselves in the process. Prisoners who were able to complete their work the fastest were rewarded with food. Needless to say, conditions were rough, and though it’s unclear exactly how many died, estimates generally run around 25,000.

Clearly, well-built infrastructure is a crucial component of the modern world. But if we can learn anything from the mistakes humans have made throughout history, perhaps we should keep in mind just how much we’ve sacrificed to reach this point and how much thought we should put into the impact of each and every project, from design to demolition and beyond.