Japanese architecture may be most closely associated with natural, lightweight materials like wood and paper, but Japan is also home to some of the world’s most incredible concrete architecture, and the two styles aren’t as disparate as they first appear. The nation’s love for a seemingly cold, unyielding material evolved out of resilience after war and natural disasters, and though the character of concrete contrasts with the organic sensibilities of tatami mats, shoji screens and hand-hewn timber, it’s not necessarily at odds with it.

Buildings in Japan are often engineered to be disposable, with an average lifespan of 25 years. Frequent earthquakes and high humidity take a heavy toll on architecture, without a doubt (though this limit was actually imposed by the country’s Land Ministry to boost the economy). Of course, not every building in Japan is razed for a new beginning after a seemingly arbitrary period of time – but the high turnover does increase demand for young architects, stimulating creative experimentation.

Japan first turned to concrete after the 1923 Great Kanto earthquake, in which 447,000 wooden houses burned. Depending on how it’s built, concrete isn’t necessarily more earthquake-proof than other materials (and earthquake building codes are still evolving today) but at least it won’t go up in flames. As it turns out, concrete is particularly well-suited to the region, offering thermal mass, resistance to moisture and versatility of form.

The devastation and subsequent Westernization of World War II ushered in a new wave of concrete while irrevocably changing Japan’s society and culture. Outside influences like the budding Brutalist architectural movement came crashing in, colliding with Japanese traditions. Le Corbusier’s National Museum of Western Art in Tokyo (1959) – his only building in the Far East – was completed with the assistance of Japanese apprentices, including Kunio Maekawa and Junzo Sakakura, and helped shape the more radical concrete architecture that was soon to come. Maekawa himself designed concrete landmarks like the Fukushima Education Center (1956).

The 1950s and 1960s brought a cascade of concrete wonders by outsiders and native Japanese architects alike, including Kenzo Tange’s Kurashiki City Hall (1957), Kiyonori Kikutake’s Sky House (1958) and Antonin Raymond’s Gunma Music Center (1961). It also saw the rise of Metabolism, Japan’s own Modernist answer to post-war rebuilding, which famously produced gems like Kisho Kurokawa’s Nakagin Capsule Tower (1972). The Olympic Games in 1964 further transformed Tokyo as scores of new buildings were commissioned, chief among them Tange’s sweeping Yoyogi National Gymnasium.

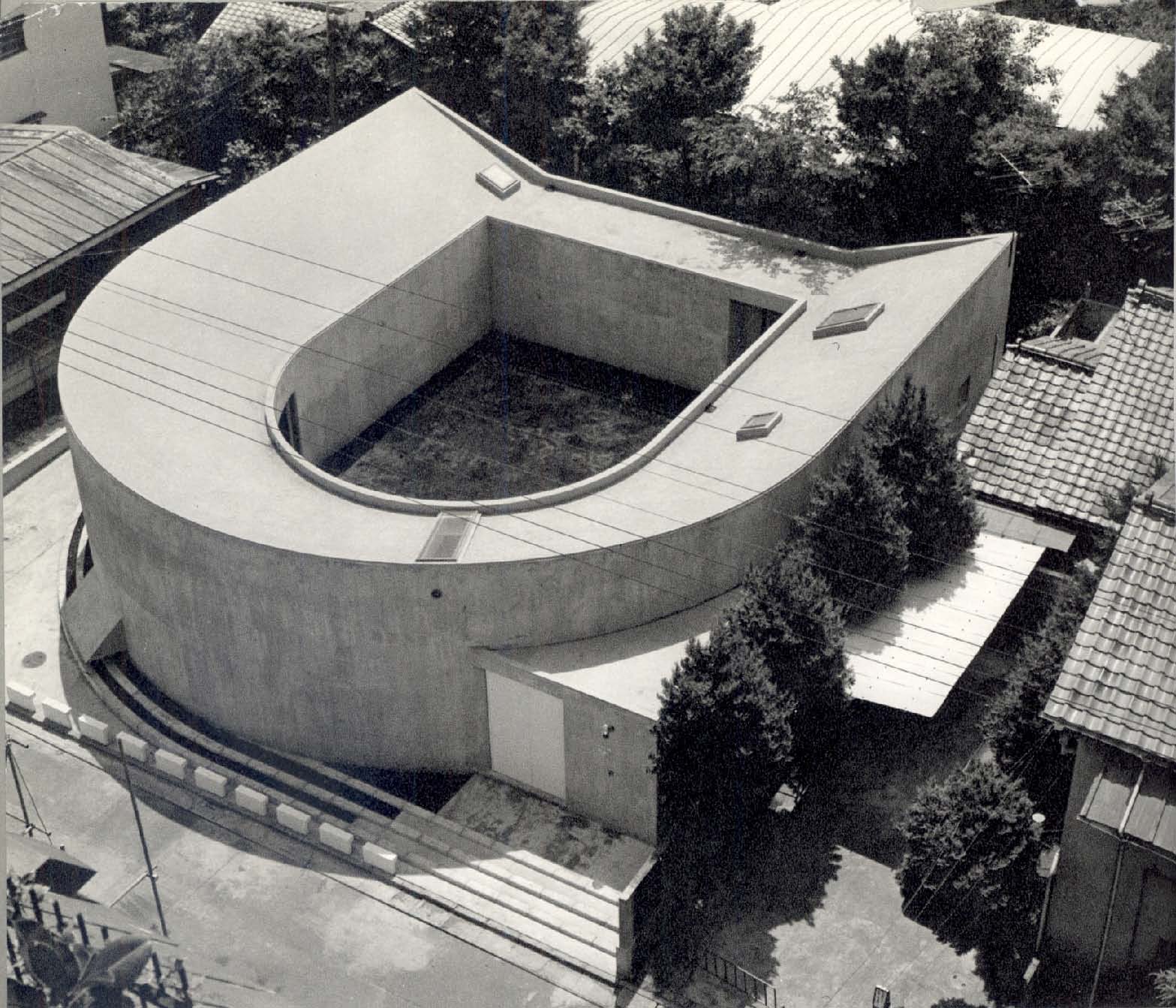

Critics of concrete architecture might say that its popularity during this period began to erode Japan’s cultural and religious connection to nature, citing particularly “harsh” examples like Toyo Ito’s windowless White U House, but others see it in a different light – literally. Early Japanese Modernists noted the way concrete retained the wooden imprint of its formwork, and how its sculptural qualities allowed them to frame natural surroundings and play with light and shadow in entirely new ways. Its simplicity implies a certain purity associated with Shinto philosophies.

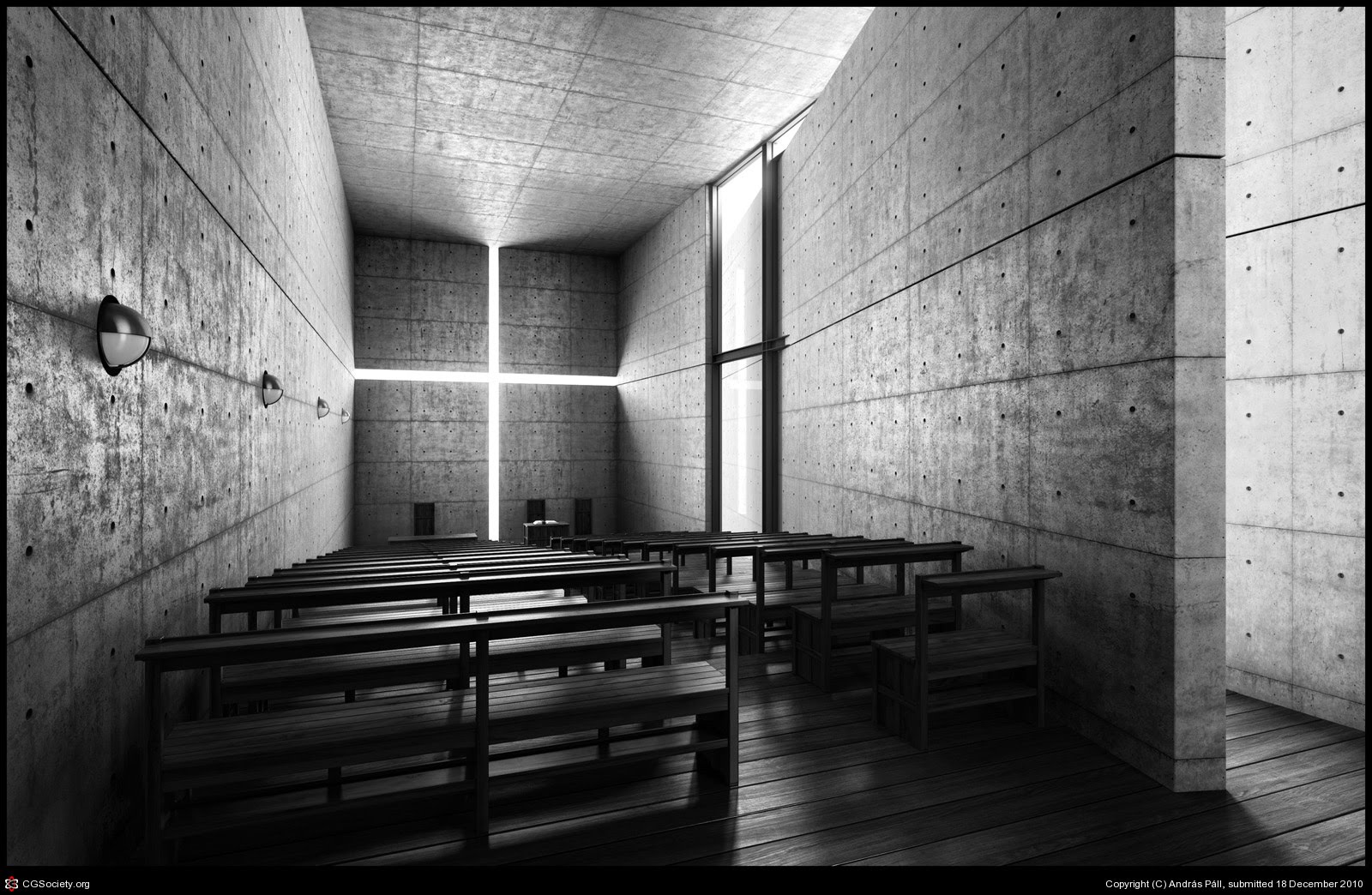

This connection is clear in the work of Osaka-born self-taught architect Tadao Ando, who built on the metaphorical foundations of Kenzo Tange’s legacy. A master of concrete, Ando skillfully sets its rawness and asceticism against the stark brilliance of natural light. Even when a structure doesn’t seem to be part of the natural world, nature can be embedded deeply within it, especially when it acts as a cathedral to hold, uplift and celebrate it. For Ando, who blended the simplicity of concrete with Japanese traditions like tatami module layouts, it’s not unlike clay in the hands of an artist, achieving forms that simply aren’t possible in wood.

That same experimental spirit flows through contemporary concrete structures. Today, concrete enables architects to continue playing with unexpected shapes, unconventional layouts and dramatic cantilevers in spaces of domestic intimacy and somber reflection. From Ryue Nishizawa’s plant-framing Garden & House to the futuristic House in Abiko by Fuse-Atelier, the material continues to shine even in all its supposed dullness.

For more concrete wonders in Japan, check out the Concrete Tokyo Map by Blue Crow Media, which identifies 50 standout structures (including a few oft-overlooked examples.)

Top image: Shinjuku Ruriko-in Byakurenge-do by Kiyoshi-Sei Takeyama + Amorphe