When we think of ancient persons carefully laying the foundations of stone monuments, or hard at work writing out historical tomes, it’s a bit hard to imagine them brushing away an interrupting cat or dog in frustration, much as we still do today.

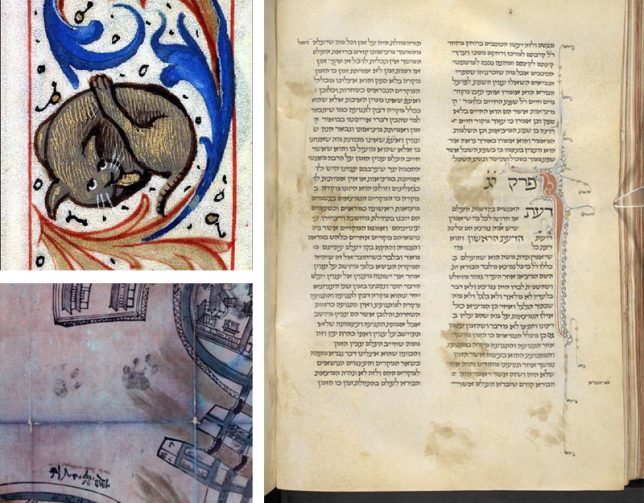

But PhD researcher Paul Cooper became fascinated with these everyday moments, frozen in time, as he began to find more and more examples — like 4,000-year-old mud bricks, for instance, “stamped with the name and titles of the Sumerian king Ur-Nammu (reigned 2047-2030 BCE) and left out to dry.”

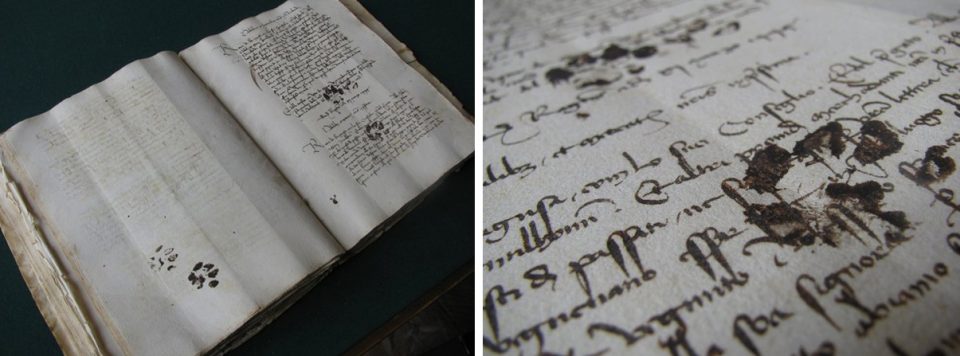

And while dogs may be less prone to hop on on tables, Cooper has found plenty of examples of cats knocking over ink and bounding across work surfaces to leave their mark, or even outright peeing on pages. The scribe of one ancient volume wrote in his text: “Here is nothing missing, but a cat urinated on this during a certain night. Cursed be the pesty cat that urinated over this book … because of it many others did too. And beware not to leave open books at night where cats can come.”

Left outside to dry, masonry materials often show signs of accidental intervention. One can find paw prints on clay tablets from the Ziggurat of Ur (21st century BCE), for example, and ancient Roman tiles (from around 0 CE) found in England, left by various species wild or domestic, including dogs, goats and sheep.