Navigable aqueducts played an important role in getting Great Britain’s industrial revolution off the ground. In an age when railroads and commercial highways had yet to be invented, these elevated artificial water bridges proved their worth at the time and have continued to do so for over two hundred years.

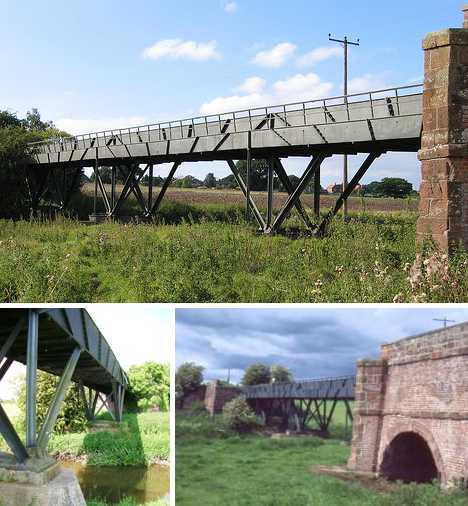

Longdon Aqueduct

(images via: DaveAFlett, The Discovering Wellington Project and Tony Clayton)

(images via: DaveAFlett, The Discovering Wellington Project and Tony Clayton)

Though British engineers were familiar with stone aqueducts dating back more than 1,500 years to Roman Britain, the Longdon Aqueduct in east central Shropshire would have impressed Caesar himself.

(images via: BurnhamMike and Captain Ahab’s Watery Tales)

(images via: BurnhamMike and Captain Ahab’s Watery Tales)

Dating from 1795, the world’s first large-scale cast iron navigable aqueduct was a vital component of the the Shrewsbury Canal system and was in use through 1944.

(image via: Narrow Boat Albert)

(image via: Narrow Boat Albert)

Though the canal has been abandoned, the Longdon Aqueduct and its accompanying towpath remain mainly intact and have been designated a Grade I listed structure. Emboldened by the success of the Longdon Aqueduct, engineer Thomas Telford moved on to bigger things: the Pontcysyllte Aqueduct in Wales.

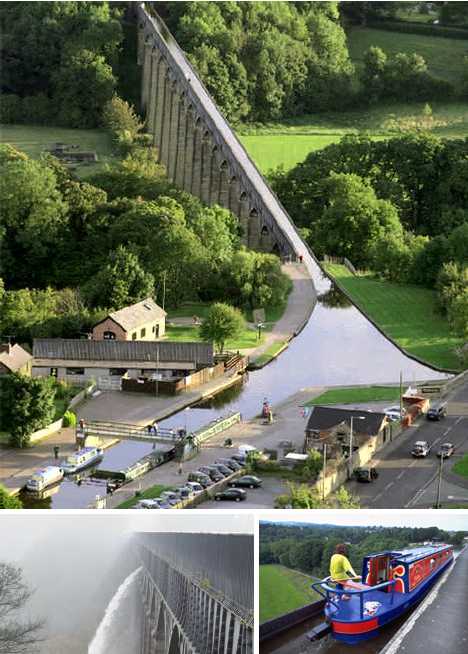

Pontcysyllte Aqueduct

(images via: Aeropic, Geograph and Webbaviation)

(images via: Aeropic, Geograph and Webbaviation)

Telford dreamed big and took his time: the Pontcysyllte Aqueduct wasn’t completed until 1805 but it still reigns as the longest and highest aqueduct in the UK. Measuring 1,007 ft (307 m) long, 11 ft (3.4 m) wide and 5.25 ft (1.60 m) deep, the Pontcysyllte Aqueduct carries the Llangollen Canal over the River Dee in Wrexham, northeast Wales.

(images via: UNESCO WHC, Waterscape and Boating Business)

(images via: UNESCO WHC, Waterscape and Boating Business)

The Pontcysyllte (pronounced “pont-ker-suth-tee”) Aqueduct may have been the height -literally – of technology at the time, but its construction involved some surprisingly unusual and ancient techniques. One example is the mortar used to cement the masonry piers: it was made from water, lime, and ox blood!

(image via: Adrian Pingstone)

(image via: Adrian Pingstone)

The Pontcysyllte Aqueduct was added to the UNESCO World Heritage List in June of 2009. The aqueduct is used regularly by pleasure boaters and commercial “narrowboats”, and once every 5 years it’s drained (by removing a plug) for cleaning and routine maintenance.

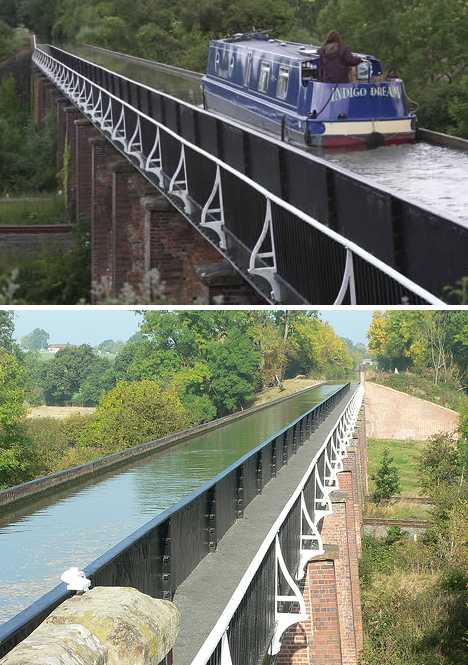

Edstone Aqueduct

(images via: Henley News and Paul Tweedy)

(images via: Henley News and Paul Tweedy)

The Edstone Aqueduct is another early cast iron aqueduct, built in the early 19th century to carry a portion of the Stratford Canal. The trough is supported by 13 brick piers that range from 8 to 11 meters (26 to 33 ft) in height.

(images via: Aqueducts of the Inland Waterways and Warwickshire Railways.com)

(images via: Aqueducts of the Inland Waterways and Warwickshire Railways.com)

A trip along the Edstone Aqueduct and its associated canal system takes one back to a time when time was not of the essence, as this video so serenely states:

EDSTONE AQUEDUCT, via PIGandPINEAPPLE

![]()

(image via: NB Bendigedig)

(image via: NB Bendigedig)

The 145 meter (475 ft) Edstone Aqueduct is the longest aqueduct in England. It spans the tracks of the former Alcester Railway line, and locomotive drivers would often top up their boilers via a convenient pipe from the aqueduct.

Avon Aqueduct

(images via: Undiscovered Scotland, Eclectech and Barrow Bob)

(images via: Undiscovered Scotland, Eclectech and Barrow Bob)

At 250 meters (810 ft) long and 26 meters (86 ft) high, the Avon Aqueduct is Scotland’s longest and tallest aqueduct. Built after a design by navigable aqueduct pioneer Thomas Telford, the Avon Aqueduct features a cast iron trough supported by 12 brick and masonry arches.

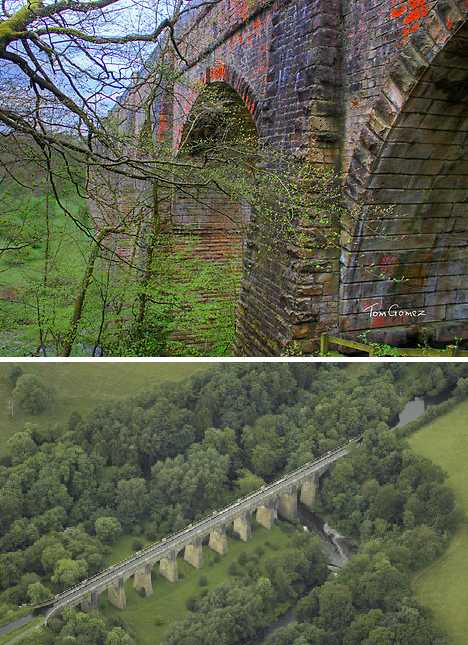

(images via: Tom Gomez / RedBubble and Scotland’s Places)

(images via: Tom Gomez / RedBubble and Scotland’s Places)

Today the Avon Aqueduct runs through Muiravonside Country Park, providing a spectacular scenic view from the park’s lush landscape or from the top of the aqueduct itself. Acrophobics be warned: an ascent to the aqueduct’s upper reaches tends to induce anxiety.

(image via: Dave Henniker)

(image via: Dave Henniker)

The Avon Aqueduct carried the Union Canal and is located near Linlithgow in West Lothian, Scotland. Three great navigable aqueducts facilitated water traffic on the Union Canal, which opened in 1822 and was closed in 1965, with the Avon Aqueduct being the largest and longest of the three.

Lune Aqueduct

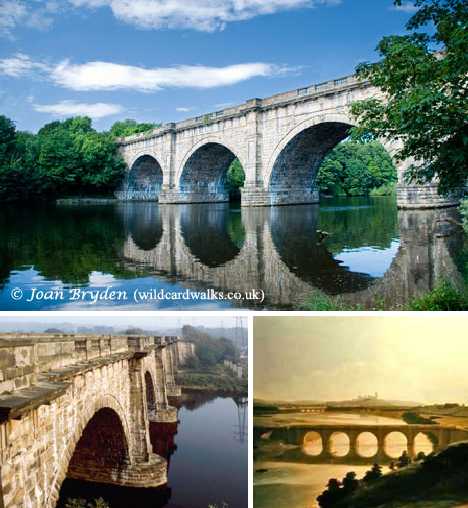

(images via: Wild Card Walks, Pitt-Dixon and 1st Art Gallery)

(images via: Wild Card Walks, Pitt-Dixon and 1st Art Gallery)

Though very much a product of the newly born Industrial Revolution, not all navigable aqueducts expressed modern designs and engineering. Take the Lune Aqueduct, which looks like it was lifted directly from an Italian renaissance tableau.

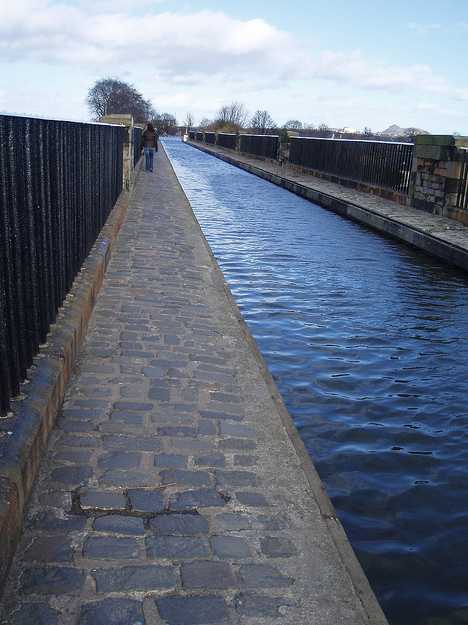

(image via: Barry CLARE)

(image via: Barry CLARE)

The Lune Aqueduct carries the Lancaster Canal over the River Lune in Lancaster, England. Designed by John Rennie following classical architectural techniques, the Lune Aqueduct supports the canal and towpath 19 meters (62 ft) over the River Lune on 5 arched brick piers. The aqueduct was built between 1794 and 1796, and its cost ran way over budget preventing the Lancaster Canal from connecting to the main canal network via the never-built aqueduct over the Ribble river.

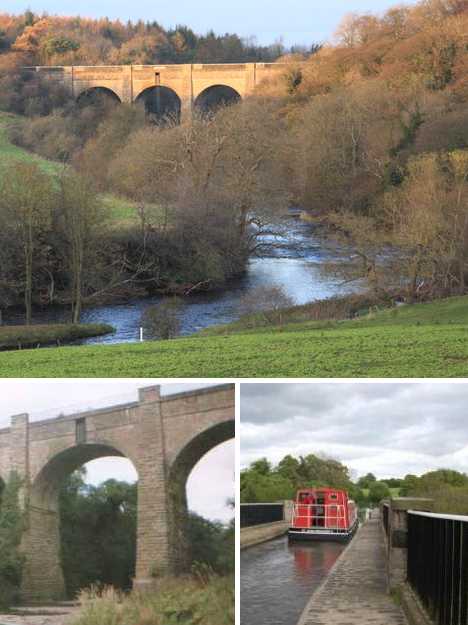

(images via: Geograph and Lancaster Guardian)

(images via: Geograph and Lancaster Guardian)

The Lune Aqueduct not only looks Roman, it was built using Roman technology adapted by designer/architect John Rennie. To ensure the stone bed of the aqueduct would not leak, Rennie specified the use of Pozzolana powder, a Roman invention that allows concrete to set underwater. Kudos to both Rennie and the Romans: the Lune Aqueduct is still in use today, though a £2-million “makeover” conducted in early 2011 should keep it humming along for another couple hundred years or so.

Slateford Aqueduct

(images via: Kim Traynor and Scotland’s Places)

(images via: Kim Traynor and Scotland’s Places)

Located in in south-west Edinburgh, Scotland, the Slateford Aqueduct is part of the Union Canal system. Completed in 1822, the aqueduct measures 180 meters (600 feet) long and is 18 meters (60 ft) in height.

(images via: Spokes and Structurae)

(images via: Spokes and Structurae)

Cyclists have made the tow path along the Slateford Aqueduct a favorite route for racing and recreation, and a network of stairways installed by local authorities has encouraged walkers and joggers to explore the area as well.

(image via: Feet First Canal Walks)

(image via: Feet First Canal Walks)

The Slateford Aqueduct carries the Union Canal over the Water of Leith (the main river flowing through Edinburgh) and Inglis Green Road. The eight-arched aqueduct was mainly used for commercial use by coal barges until competition from railroads made such slow transport unprofitable.

Almond Aqueduct

(images via: Olympiaa, CanalPlan AC and PerryWeb)

(images via: Olympiaa, CanalPlan AC and PerryWeb)

The 130 meter (420 ft) long Almond Aqueduct carries the Union Canal 23 meters (76 ft) over the River Almond and, in its day, helped reduce the travel time between Edinburgh and Glasgow to a mere 13 hours.

(images via: Geograph and Paul Hicks)

(images via: Geograph and Paul Hicks)

The liquid nature of all navigable aqueducts’ “roads” means water levels rise and fall depending on a variety of factors, mainly rainfall in the region. As such, most large navigable aqueducts were built with overflow outlets much like the one in your bathroom sink. Above you can see water spewing forth from the Almond Aqueduct’s overflow outlet, taken from the top and looking down.

(image via: Citizenthom)

(image via: Citizenthom)

Freeze frame! The above photo captures a spectacular icicle that formed from water exiting the Almond Aquaduct’s overflow channel during a sharp cold spell in January of 2009. The flash-frozen flood compares with the legendary Broxburn icicle, which stretched 22.8m (75ft) long in 1895.

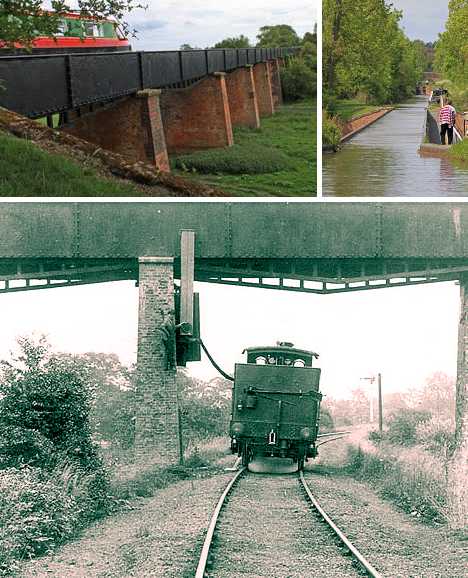

Chirk Aqueduct

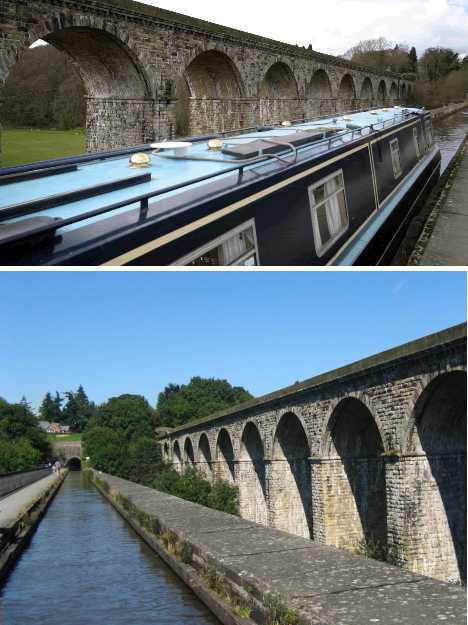

(images via: Narrow Boat Hire and Charnwood Cam)

(images via: Narrow Boat Hire and Charnwood Cam)

Chirk Aqueduct is a 21 meter (70 ft) high, and 220 meter (710 ft) long navigable aqueduct that carries the Llangollen Canal from Wales to England, or vice versa. Completed in 1801 after a 5-year-long construction period, Chirk Aqueduct is another Thomas Telford design with a cast iron trough concealed by masonry walls and piers.

(image via: MAntunes)

(image via: MAntunes)

A railway viaduct was later added alongside the Chirk Aqueduct, designed with the same style and basic construction methods though its quite a few years more recent.

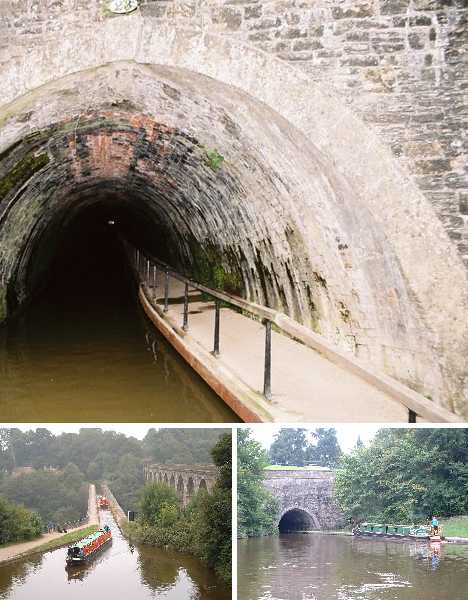

(images via: Your Local Web and Gerry Cork)

(images via: Your Local Web and Gerry Cork)

Cruising the Llangollen Canal over the Chirk Aqueduct takes a twist when, just beyond the northern end of the aqueduct, the canal flows into the Chirk Tunnel complete with towpath. It must have been a unique experience towing coal barges through the 420 meter (nearly 1,400 ft) long tunnel.

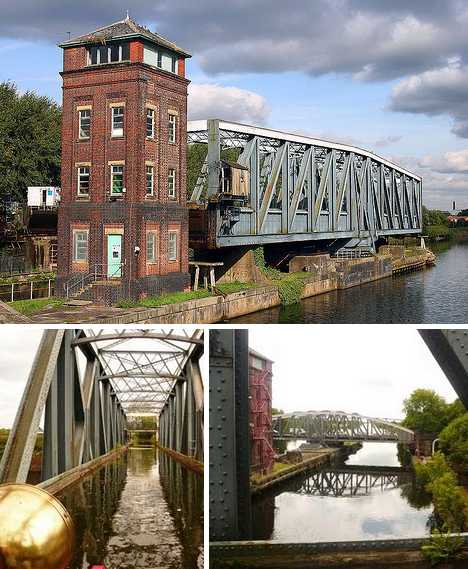

Barton Swing Aqueduct

(images via: John Eyres and Narrowboat Tacet)

(images via: John Eyres and Narrowboat Tacet)

The poster child for 19th century British engineering has to be the Barton Swing Aqueduct, opened in 1894 to replace a stone aqueduct built in 1761. Directed from a brick control tower situated on an island in the Manchester Shipping Canal, this ingenious swinging aqueduct allows the Bridgewater Canal to cross the newer shipping canal by spinning 90 degrees.

(image via: Vince’s World)

(image via: Vince’s World)

The tower also controls a swinging road bridge slightly upstream but still pivoting on the island. When in use, both bridge and aqueduct swing around to line up along the longitudinal axis of the island. Here’s a cool video of the Barton Swing Aqueduct doing what it does best:

Barton Aqueduct, via NBKeepingup

![]()

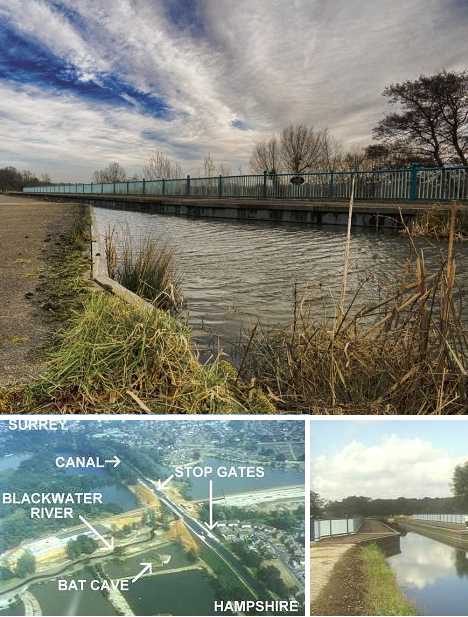

Ash Aqueduct

(image via: Geograph)

(image via: Geograph)

Two hundred years after the first cast-iron navigable aqueduct appeared in Great Britain, the Ash Aqueduct officially opened. Two centuries is a long time for a certain technology to remain in use, relatively unchanged, but perhaps Thomas Telford was a man ahead of his time.

(images via: Renderosity and Basingstoke-Canal.org)

(images via: Renderosity and Basingstoke-Canal.org)

The Ash Aqueduct officially opened in June of 1995 and, unfortunately, graffiti taggers wasted no time in welcoming it to the ‘hood. The aqueduct’s stated purpose is to carry the Basingstoke Canal from Surrey into Hampshire, over the Blackwater River.

![]()

(image via: Ministry)

(image via: Ministry)

“Things that are wanting are brought together / Things remote are connected / Rivers themselves meet by the assistance of art / To afford new objects of commerce.” So reads the inscription (translated from Latin) on the south side of the Lune Aqueduct. This wonderful expression of romantic optimism reflected the era’s belief that art and science working together could accomplish great things for great public benefit. The UK’s navigable aqueducts helped realize that hope.