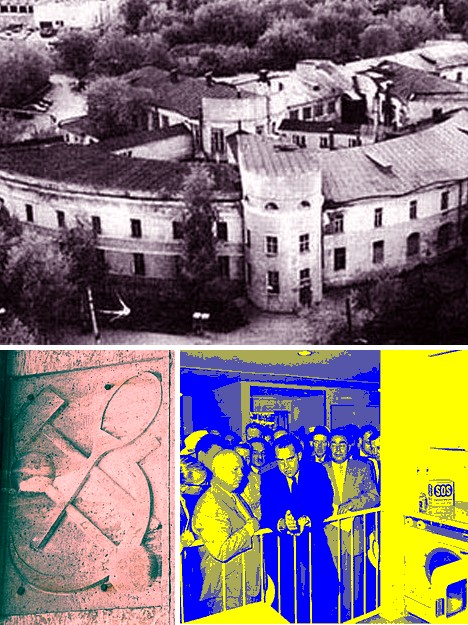

The hammer & sickle shaped Maslennikov Kitchen Factory, located 500 miles southeast of Moscow in Samara, once stood at the pinnacle of the Soviet Constructivist architecture movement. Today, as a date with the wrecking ball looms ever closer, this iconic abandoned building stands as a battleground between Russia’s grassroots architectural preservationist movement and shady developers looking to make a fast ruble once the building is rubble.

(image via: Archnadzor)

(image via: Archnadzor)

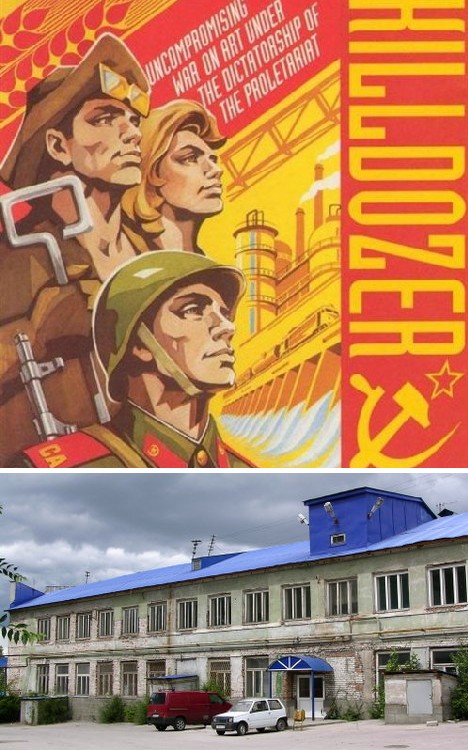

Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, 1932… the acrid smoke of the Russian Revolution still permeates the air, while Stalin’s iron boot has yet to crush the bright hopes and soaring aspirations of a nation proudly waving the flag of a new ideology. In this narrow historical window between the World Wars, it seemed most anything was possible. Creative movements in art and architecture were allowed free reign as Russians shook off the stereotype of backwardness, ignorance and xenophobia like a bad case of fleas.

(images via: Fotki Yandex and World of Level Design)

(images via: Fotki Yandex and World of Level Design)

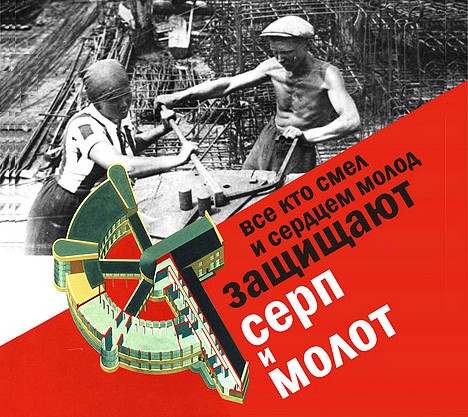

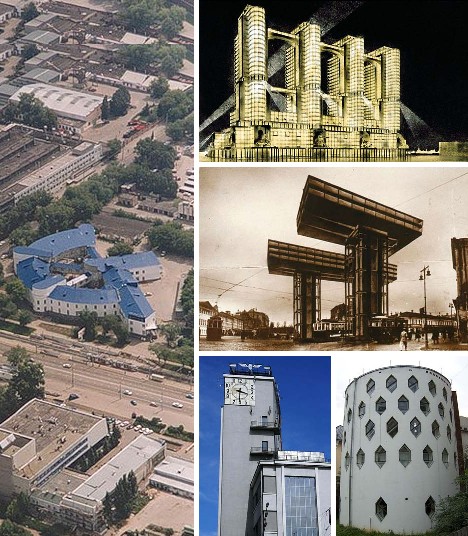

Out of this fermenting stew of creativity rose new ways of artistic expression such as Futurism, Suprematism and Constructivism. The latter movement, an outgrowth of Russian Futurism, sought to meld avant-garde design with the practical engineering required to facilitate everyday living. Sponsored and supported by the Soviet leadership, Constructivist buildings large and small began to rise from one end of the vast USSR to the other. Factories, offices and apartment blocks displayed modern outlines exemplified by vast expanses of light-admitting glass windows.

(images via: Workers of the World Unite, Putri Purwandani and Russia Beyond the Headlines)

(images via: Workers of the World Unite, Putri Purwandani and Russia Beyond the Headlines)

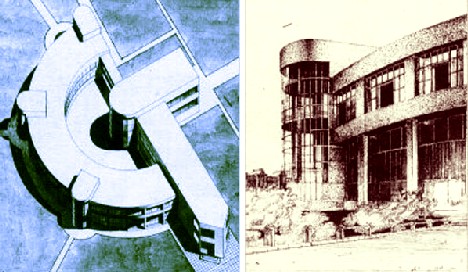

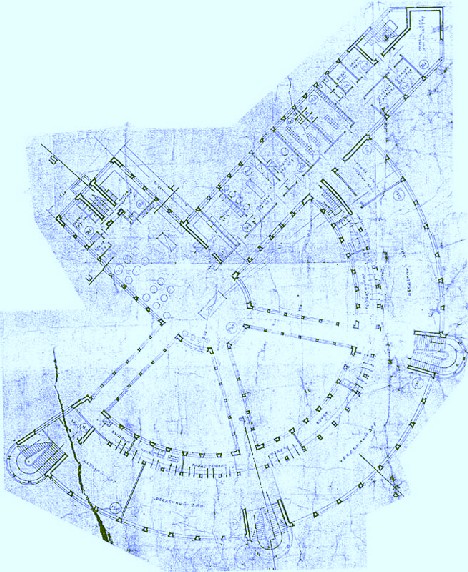

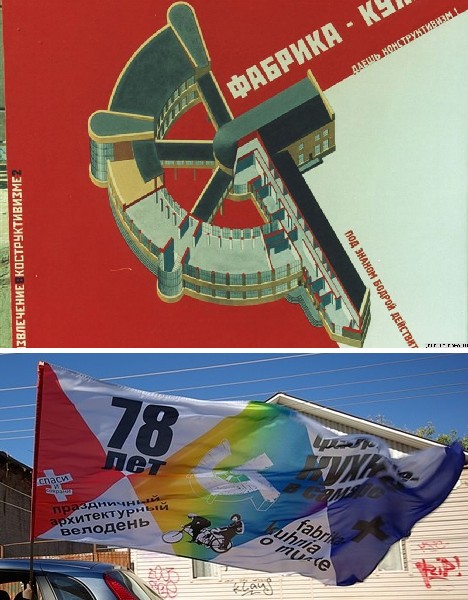

This utopian creative era was not to last – as Joseph Stalin consolidated his grip on all aspects of Soviet life, he began to see the free-wheeling aspirations of the Constructivists as a threat. One of the last major state-sponsored works of Constructivist architecture was the massive Maslennikov Kitchen Factory in Samara, built between 1930 and 1932. Resembling a gargantuan, stylized Hammer & Sickle in horizontal plan, the look of the “Fabrika Kukhnya” didn’t upset Uncle Joe as much as the innovative thought processes that went into its design.

(images via: Archnadzor and Snegourotchka)

(images via: Archnadzor and Snegourotchka)

According to Moscow-based architect Vitaly Stadnikov, in its heyday the Maslennikov Kitchen Factory served more than 9,000 meals at a time to workers at the neighboring military components manufacturing complex. “The factory was designed to feed the whole workforce for each factory shift,” explained Stadnikov. “Because of its unique composition, the canteen (dining area) was in the sickle, administrative offices were in the handle of the hammer, and the kitchen was in the head of the hammer.”

(images via: URBAN3P, Region Samara and Samara On Foot)

(images via: URBAN3P, Region Samara and Samara On Foot)

The Maslennikov Kitchen Factory was ground-breaking in a number of ways, starting off with its female architect, Yekaterina Maksimova. Tasked with constructing the building in the shape of communism’s twinned symbols, Maksimova made certain compromises that aided the finished building in performing its function with smoothness and efficiency. Once the meals were prepared in the hammer’s head, three conveyor belts delivered the cooked food to distribution points in the sickle-shaped canteen. The factory building also housed a gymnasium, a reading room and other health and recreation related services.

(images via: Arguments and Facts – Samara, Eternal Remont and Owen Hatherley)

(images via: Arguments and Facts – Samara, Eternal Remont and Owen Hatherley)

The Maslennikov Kitchen Factory was the first building in Samara to be made out of reinforced concrete, considered to be an expensive luxury at the time. The choice of construction materials undoubtedly helped the building survive over the decades, as did regular maintenance and upkeep. A Stalinist makeover in 1944 (above, top) added a heavy-handed, neoclassical look to the facade but some portion of the original appearance was restored in 1988. It’s notable that the kitchens were still in operation at that time, over 55 years since they first began operation.

(images via: Architectural Walk)

(images via: Architectural Walk)

A shopping center and several sports clubs occupied the building up to the mid-1990s but for the past few years the structure has been empty of tenants. Maintenance and repairs were withheld and the once-proud symbol of Soviet socio-economic progress steadily deteriorated.

(image via: Architectural Walk)

(image via: Architectural Walk)

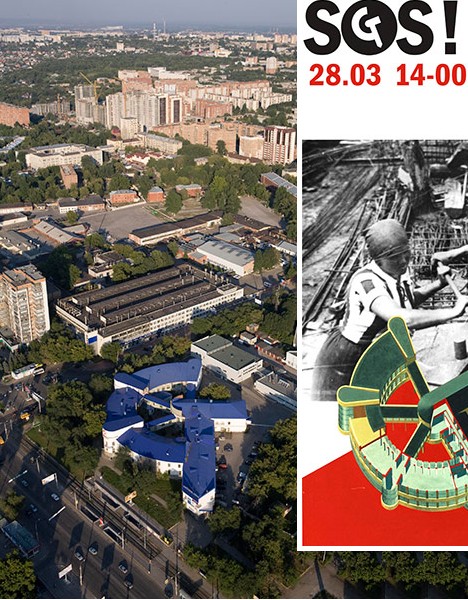

Several years ago the abandoned canteen was bought by Clover Group, a property developer headquartered in Moscow, with the intention of redeveloping the site. In April of 2008, the daily newspaper Noviye Izvestia reported that Clover Group intended to demolish the complex, which by that time occupied an increasingly valuable plot in downtown Samara, Russia’s sixth-largest city.

(images via: Bookcase.com and Architectural Walk)

(images via: Bookcase.com and Architectural Walk)

The looming loss of the Maslennikov Kitchen Factory galvanized a grassroots movement among architectural preservationists within Russia and abroad, as well as rallying local citizens to realize their city’s cultural legacy was rapidly slipping away. “Constructivist architecture can function beautifully in the fabric of a contemporary city,” said Clementine Cecil, one of the founders of MAPS (Moscow Architecture Preservation Society). “It was built in the golden era of Soviet Architecture,” continued Cecil. “Just because its not in Moscow or St. Petersburg, doesn’t mean it should be ignored. It is such a unique and exciting example of Constructivism.”

(images via: Chtodelat News and Notes of Samara Everyman)

(images via: Chtodelat News and Notes of Samara Everyman)

Samara, Russia, September 26th, 2010… Workers and residents out for a Sunday stroll through downtown were greeted by a sight exceedingly rare in post-communist Russia: Dozens of cyclists riding circles around Samara’s “Hammer and Sickle Canteen”, raising awareness of the building’s precarious status in the shadow of the developers’ wrecking ball.

(images via: Seleste-Rusa and Architectural Walk)

(images via: Seleste-Rusa and Architectural Walk)

The Veloden (Bike Day) protest was organized through a viral campaign with a strong online component though the use of Soviet-style, Constructivist-inspired imagery is only slightly ironic.

(images via: Radio Free Europe and Notes of Samara Everyman)

(images via: Radio Free Europe and Notes of Samara Everyman)

In the meantime, land values in downtown Samara continue to rise and the presence of an abandoned, obsolete, giant kitchen is, to some, increasingly irksome. “What are these New Russians thinking?”, wondered architect Andrei Gozak. “They’re hurting themselves; they’re destroying something that is actually worth something, and what they want to do is actually worth nothing – they just don’t know it.”

(images via: Architectural Walk and Notes of Samara Everyman)

(images via: Architectural Walk and Notes of Samara Everyman)

According to preservation campaigners in Samara, “any demolition would be illegal because the site is on a list of buildings that are pending landmark status.” That status has been pending for 17 years now, which plays into the developers’ hands: time is on their side as the now-abandoned building inexorably deteriorates. An “accidental” fire here, a “ruptured” water main there, and sooner or later the building will be too far gone to repair.

(images via: Open Democracy Russia and Notes of Samara Everyman)

(images via: Open Democracy Russia and Notes of Samara Everyman)

Does that sound paranoid? Clementine Cecil doesn’t think so, after receiving some friendly advice from a local businessman with connections to the Samara city government last summer. “I advise you and your colleagues to stop defending this building,” warned the shadowy insider. “It would be better if the building just burnt down. Yes, that would be a lot simpler.”

(images via: Guardian UK and Guardian UK)

(images via: Guardian UK and Guardian UK)

Can the Maslennikov Kitchen Factory head off the heavy-handed, short-sighted, tight-fisted capitalists of the New Russia long enough to celebrate its 100th anniversary in 2032? Are newly minted laws in the post-communist nation strong enough to withstand the pressures of self-interested mafiosi and corrupt bureaucrats?

(image via: Samara Today)

(image via: Samara Today)

“The new interest in constructivist buildings in Moscow should set a precedent for the regions,” summed up Clementine Cecil. “This is a building that should be cherished by Samara.” Let’s hope it will be, by ours and future generations.