Nearly 4,000 years ago, Cornish miners singlehandedly jump-started the Bronze Age by digging, scratching and clawing copper and tin ores from mines hacked deep beneath Cornwall’s fertile soil. Though the mines have now all closed, dozens of abandoned stone engine houses mark the spots where Cornish metal, mines and miners transformed a landscape and a nation.

Caesar Sailed

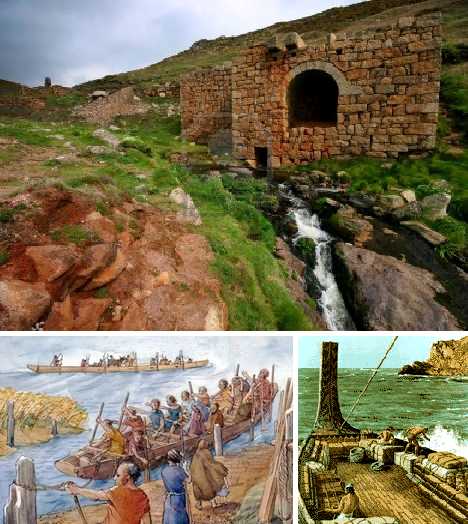

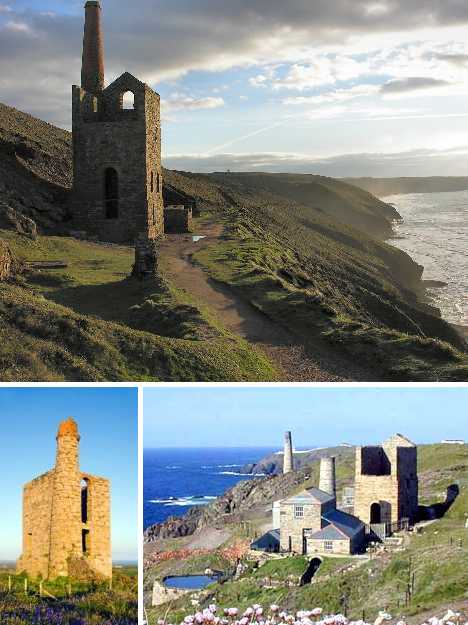

(images via: 123RF, Sott.net and Cornish Legends)

(images via: 123RF, Sott.net and Cornish Legends)

Tin mined in Cornwall was one of Britain’s first internationally traded commodities and the earliest evidence of tin mining there dates back nearly 3,000 years. History’s first great traders, the Phoenicians, sailed to the British Isles for centuries, trading exotic Mediterranean art and artifacts for rough ingots of Cornwall tin.

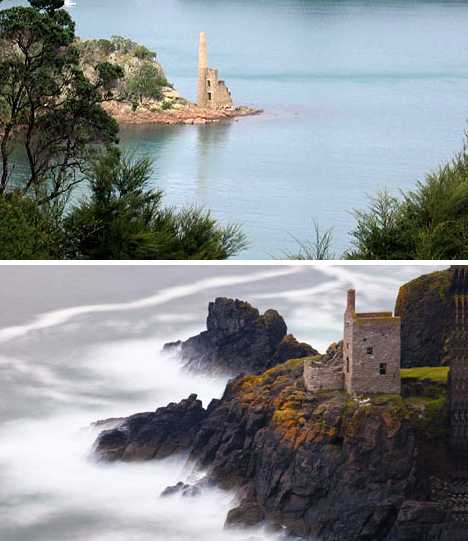

(image via: Tristan Barratt)

(image via: Tristan Barratt)

Such was the importance of the ancient tin trade, the British Isles were known as the Cassiterides, or the “Tin Islands”.

(images via: Nigel Breen, BBC and Cornwall 365)

(images via: Nigel Breen, BBC and Cornwall 365)

The Romans’ desire to control the European economy (and the lucrative tin trade) was one factor which led to the Roman invasion of Britain in the year 43 AD. The Romans came to stay, after following up on two pioneering expeditions led by Julius Caesar nearly a century earlier.

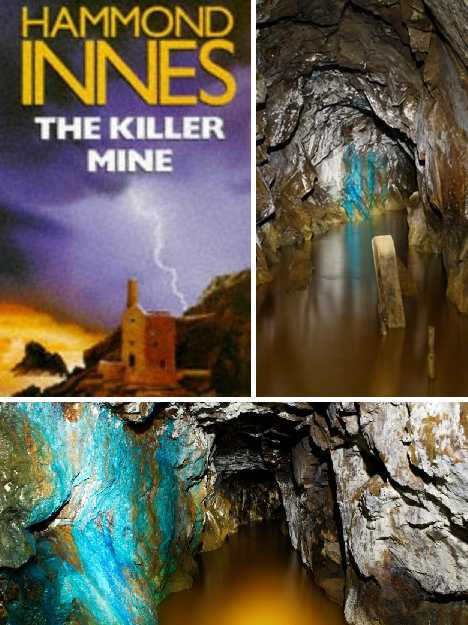

(images via: Bish’s Beat and 28DL)

(images via: Bish’s Beat and 28DL)

Of the natural tin ore originally found in Cornwall little if any remnants remain – early miners exploited surface seams long ago and as time passed, were forced to dig ever deeper when bands of tin ore angled deep into the ground. They soon encountered a problem: upon reaching the water table, mine shafts and galleries would flood.

The Dream of Steam

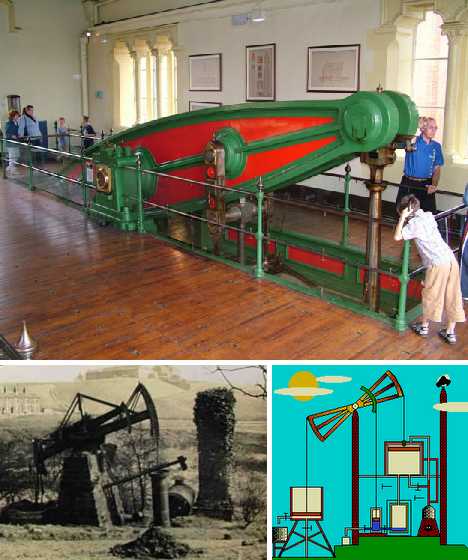

(images via: Wendy House, Age of Revolution and WIRED)

(images via: Wendy House, Age of Revolution and WIRED)

By the sixteenth century, German miners had begun exploiting Cornwall’s copper reserves but flooding was a constant worry. In the meantime, England’s rise as a global power boosted the need for copper and tin.

(image via: Tristan Barratt)

(image via: Tristan Barratt)

Intense demand for Cornwall’s resources compelled engineers to experiment with various types of technologies that could enable mines to be dug deeper. One of the first successful remedies involved pumps powered by primitive steam engines.

(image via: Aditnow)

(image via: Aditnow)

In 1689, gunpowder was first used to blast mine tunnels. Concurrently, various “atmospheric engines” and a steam-powered pump called the “Miner’s Friend” were proving it was possible to remove water from underground mines by mechanical means. By 1715, an improved and standardized steam engine designed by Thomas Newcomen was in place at the Wheal Vor mine (above).

(images via: Cornish Mining, The Cornwall Tapes and Cornwall Council)

(images via: Cornish Mining, The Cornwall Tapes and Cornwall Council)

Newcomen’s engines featured a steam boiler driving a single piston that acted upon a large rocking beam. the reciprocating piston, while slow by modern standards, was sufficient to work the pump mechanism suspended from the opposite end of the beam. Throughout the nineteenth century Newcomen engines were incrementally improved, including a notable development in 1769 by James Watt that boosted efficiency while lowering fuel costs.

(image via: Genius Loci)

(image via: Genius Loci)

When Newcomen’s patents began to expire in the 1790s, Watt’s next-generation steam engine design combined with new, high-pressure steam boilers invented by Cornish native Richard Trevithick quickly supplanted the comparatively inefficient Newcomen engines.

Engines in the House!

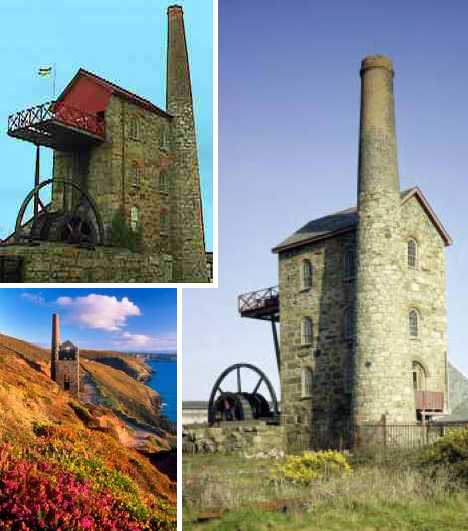

(images via: CornwallCam, Science Photo Library and Cornish Holiday Cottages)

(images via: CornwallCam, Science Photo Library and Cornish Holiday Cottages)

As Cornish mines adopted Watt’s steam engine en masse, a unique form of architecture created in Cornwall sprung up to enclose the engines and quickly became to standard. These so-called “Engine Houses” were made from local materials and employed an economic style that still managed to be attractive and appealing.

(images via: Cornish Mining Heritage Programme and Guardian UK)

(images via: Cornish Mining Heritage Programme and Guardian UK)

Stone was necessary to support the engine’s massive rocking beam, as well as to help insulate the steam boilers from Cornwall’s often chill ocean breezes. The vertical orientation of the piston is reflected in tall walls while the constant fire beneath the boiler required a soaring smokestack.

(image via: Tristan Barratt)

(image via: Tristan Barratt)

The pump mechanism was usually exposed to the elements and as little if any solid infrastructure was needed for support, the main function of a typical Cornwall engine house is not always clear to a modern visitor.

(images via: Cornwall Guide and The Magic of Cornwall)

(images via: Cornwall Guide and The Magic of Cornwall)

Economy and functionality may have been the watchwords in engine house construction, but Cornish engineers still endeavored to add certain decorative refinements. Most notable among these were arched “Romanesque” windows framed on their upper portions with a curved row of brickwork.

(images via: 123RF, Fotolibra and Jon Law)

(images via: 123RF, Fotolibra and Jon Law)

The smokestacks as well display a pleasant symmetry as they gracefully taper from base to cap. Cornish stonemasons used every iota of their prodigious skill to craft these enduring monuments to metallurgy, a feat even more remarkable when the only available construction material was rough and uneven local rock.

Cornwall’s Stone Walls

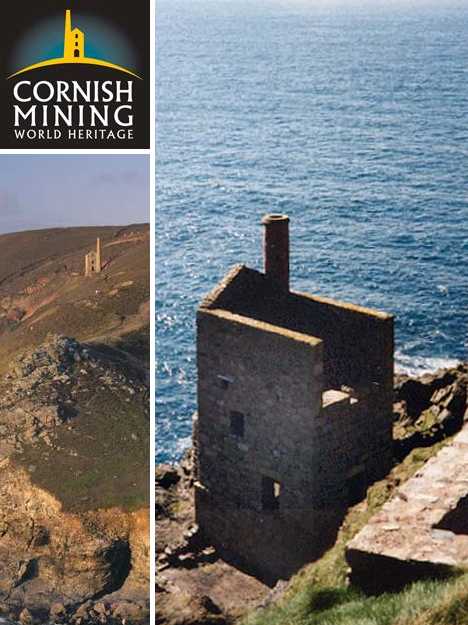

(image via: Cornish Mining World Heritage)

(image via: Cornish Mining World Heritage)

At its peak in the 1850s, over 50,000 Cornish men, women and children worked in dimly lit mines up to 1,000 meters (3,500 ft) deep. Approximately 600 steam engines diligently pumped water from mines, some of whose galleries extended into the bedrock underlying the ocean!

(images via: The Intuitive Lens and COST)

(images via: The Intuitive Lens and COST)

It was not to last, however. In just a few short years, substantial discoveries of tin ore in Bolivia, Australia and Malaysia caused the bottom to drop out of the tin market and Cornish mines closed, one after another.

(image via: Geevor Tin Mine Museum)

(image via: Geevor Tin Mine Museum)

In the first half of 1875 alone, over 10,000 Cornish miners left their homeland to seek work in mines around the world. The final mine to close was South Crofty in 1998… it had operated nearly continuously since the 1590s.

(images via: Tristan Barratt)

(images via: Tristan Barratt)

Among the many breathtaking images selected for this post, the amazing light-painted photos created by Tristan Barratt stand out.

(image via: Tristan Barratt)

(image via: Tristan Barratt)

Barratt’s photographic techniques add a hauntingly beautiful aura to Cornwall’s abandoned stone engine houses that would be simply unimaginable to the hardscrabble miners who saw these structures in quite a different light back in their gritty heyday.

(images via: HDC, UNESCO and Bath Parade Guides)

(images via: HDC, UNESCO and Bath Parade Guides)

On May 15th, 2007, the Cornwall and West Devon Mining Landscape – including Cornwall’s derelict and abandoned mine engine houses – was officially designated a World Heritage site by UNESCO.

(images via: Lapsus Kalamari, Roger Cook and Cornwall Guide)

(images via: Lapsus Kalamari, Roger Cook and Cornwall Guide)

At the ceremony, Dr Mechtild Rössler, Chief of the Europe and North America Section at the World Heritage Centre, described the Cornwall and West Devon World Heritage site as being “one of the great industrial landscapes of Europe”.

(image via: Geevor Tin Mine Museum)

(image via: Geevor Tin Mine Museum)

Prince Charles, who accepted the certificate from Dr Rössler, stated that “Cornish mining shaped the mining world in a dynamic way.” Not to mention the way it shaped, re-shaped and now symbolizes the distinctively scenic beauty of Cornwall, a land where Man and nature have combined to create a treat for the eyes and a salve for the soul.