Portugal’s Cemitério das Âncoras, or “Anchor Graveyard”, sprawls across the shifting sand dunes of Barril Beach on Tavira Island. Lined up on edge with near-military precision, hundreds of rusted anchors memorialize southern Portugal’s long-lost tuna fishery and the generations of fisher-folk whose livelihoods vanished along with the fish.

Ironic Beauty

(image via: Jurgis Karnavicius)

(image via: Jurgis Karnavicius)

Tavira Island (Ilha de Tavira) hugs southern Portugal’s scenic Algarve shoreline, it’s long and slender dimensions hugging the coast for 6.85 miles (11 km). Part of the Ria Formosa nature reserve, Tavira Island (Google map here) boasts some of the Algarve’s best beaches, some of which are favored by naturists.

(image via: Tavira Guide)

(image via: Tavira Guide)

Take a few steps back from the beach – not too many, as the island is only 500 ft to 3,300 ft (150 m to 1 km) wide – and you’ll find a curious sight among the shifting sand dunes: a graveyard of anchors.

(images via: Johan Van Moorhem)

(images via: Johan Van Moorhem)

Interestingly, the upturned tips of the half-buried anchors strikingly resemble some of the standing sea stacks characteristic of the Algarve coast.

(images via: Chica_de_Ayer and TaviraApartment.net)

(images via: Chica_de_Ayer and TaviraApartment.net)

The Cemitério das Âncoras, as it’s known in Portuguese, is an odd and unexpected assemblage of several hundred iron anchors. Gnarled and rusted from years of use and even more years of disuse, the anchors are positioned on their sides with one hook looping into the air and the other driven into the island’s moist, welcoming soil.

Anchor Species

(images via: Vale Grifo and Fine Art America)

(images via: Vale Grifo and Fine Art America)

There is no exclusionary fence at the Anchor Graveyard, no sign or signal as to who made it and for what purpose. What little we know, we have learned from the remaining descendants of the people who, for many generations, exploited the formerly abundant bluefin tuna that once plied the wild waves just offshore.

(image via: Joaollq)

(image via: Joaollq)

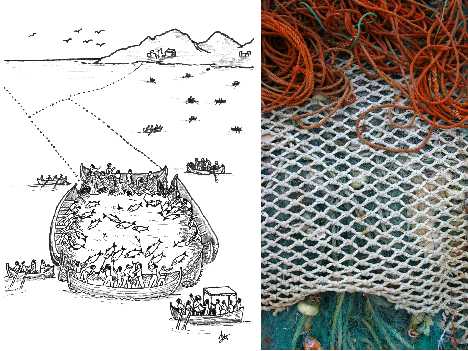

The rough and unpredictable waters where the Atlantic meets the Mediterranean called for a unique tuna-fishing technique invented long ago, perhaps by the ancient Phoenicians who first explored and colonized the area before the Romans built an Empire.

(images via: Tavira Guide, Gustavo Muleey and Documenting Reality)

(images via: Tavira Guide, Gustavo Muleey and Documenting Reality)

The anchors might look like those used to hold small ships steady but they weren’t used for that purpose. Instead, Portugal’s traditional tuna fishermen used them to hold their huge funnel nets (“armações de atum”) in place against both the force of the sea and the exertions of massive, trapped bluefin tuna.

(images via: Herman van Steenwijk and Ana Cruz)

(images via: Herman van Steenwijk and Ana Cruz)

Tuna are fierce predators of smaller fish and have always existed near the top of the food chain… until humans came along. Overfishing over the centuries and desperate competition between fishermen eventually resulted in the bluefin population crashing, never to recover. No longer needed to hold down nets designed to catch a vanished resource, the anchors found their way to the dunes of Tavira Island, there to become a collective memorial to a lost way of life.

Net Gains & Losses

(images via: John in Scotland, The Daily WTF and Fogonazos)

(images via: John in Scotland, The Daily WTF and Fogonazos)

It’s not certain exactly who was the first to line up an anchor or anchors out among the silent dunes or when that fateful decision was made, but evidently those who followed thought it was an idea worth emulating.

(image via: Rufias)

(image via: Rufias)

What IS known for sure is that the Anchor Graveyard of Tavira Island is no longer growing: the tuna-fishing fleet has long gone from the island’s sunny shores and like the tuna, the anchors are no more.

Here’s a very short video of the Anchor Graveyard that gives a more “moving” perspective of this metallic menagerie:

Praia do Barril, Cemitério de âncoras, via Ellsam23

![]()

(images via: Rufias, Fotopedia and HubPages)

(images via: Rufias, Fotopedia and HubPages)

One would think that hundreds of discarded iron anchors could fetch a pretty peseta as scrap metal but, thankfully perhaps, that hasn’t happened. It may be that the people of Tavira Island and of Portugal’s Algarve respect their ancestors too much and, as they did, mourn the loss of their traditional lifestyle and livelihood.

(image via: Ana Cruz)

(image via: Ana Cruz)

Loss and loneliness… it’s what defines graveyards of all types but if you try sometimes, you can look past the sadness and find something to celebrate. The above images by Ana Cruz, an artist and photographer who goes by the name Cakau, teases out a positive note courtesy of her traveling companion, Tabitha. Among the irony, there is a kind of beauty.