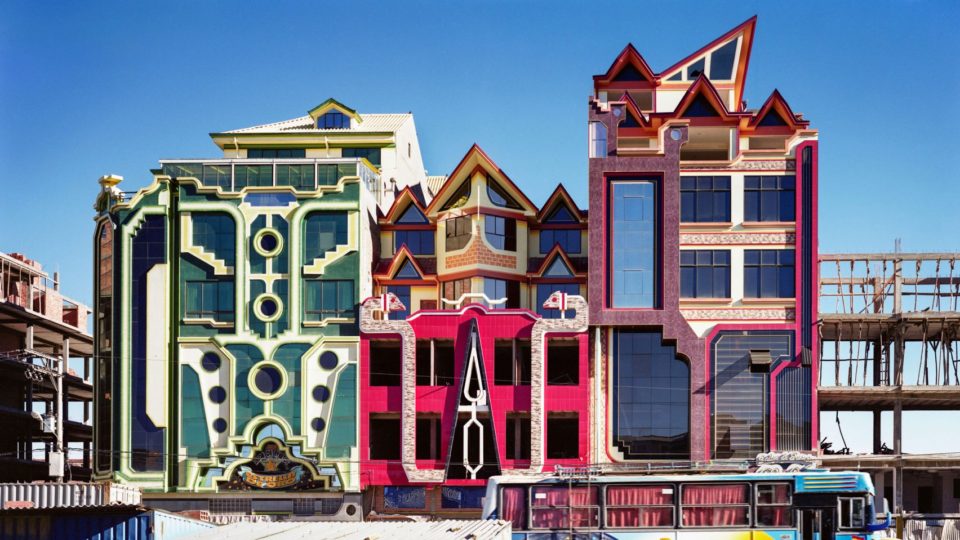

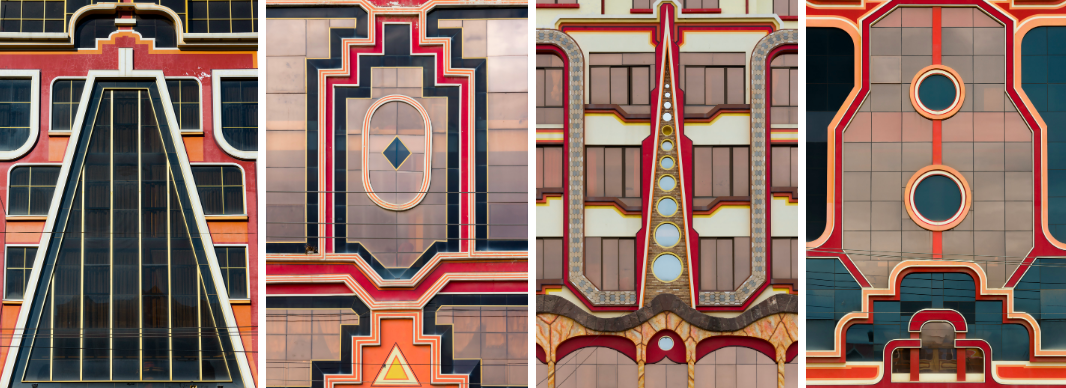

Whether you love it or hate it, the divisive architectural style taking over the Bolivian city of El Alto is certainly a departure from the norm, injecting bold shapes and colors into an otherwise average cityscape. Local architect Freddy Mamani, who has spent the last 18 years developing the signature style he calls “Nuevo Andino” (“New Andean”), felt that El Alto was too “monochrome.” Each of his buildings is like a unique sculptural work of art aiming to enliven the city and pay homage to ancient indigenous motifs of the area.

To understand and appreciate Mamani’s daring design decisions, it helps to know a little about the area’s history. El Alto is a the second-largest city in Bolivia outside the capital city of La Paz, and one of its fastest-growing urban centers. As millions of people have moved in from rural areas, El Alto has rapidly developed architecture and infrastructure to accommodate them. Most of the city’s residents are Amerindian, identifying as Aymara, an indigenous nation in the Andes and Altiplano regions whose ancestors lived in the area long before becoming subjects of the Inca in the 15th century and later the Spanish in the 16th century.

Centuries of colonization can wreak havoc on indigenous cultures, suppressing them (often violently) in the name of assimilation. The colors and forms of the Aymara spring back to life in a way that simply can’t be ignored through Mamani’s work. Locally, the buildings he has erected – as well as those inspired by his work – are referred to as “cholets,” reclaiming a derisive word combining “chalet” and “cholo” often used to dismiss the indigenous population in Latin American countries.

Each of these “cholets” has commercial space on the ground floor for shops, restaurants and services, while the second floor hosts a gathering space, the third offers apartments and the fourth contains the residence of the building’s owner. They all feature exaggerated geometries, asymmetrical proportions and the lines and motifs found in the ruins of the ancient Aymara city of Tiwanaku, a UNESCO World Heritage Site located about 37 miles away. Mamani has completed about 70 of these buildings in El Alto and 100 more across Bolivia.

While observers from around the world have sometimes derided the buildings with words like “ugly,” “rotten” and “gruel,” Mamani’s cholets simply weren’t made for them and don’t require their approval. Brash design choices may not be for everyone, but as many cities continue to homogenize and lose their cultural identities, some fight back against bland one-size-fits-all trends. And in El Alto, that has meant drawing in travelers who come just to take in the uniqueness of the city.

Dezeen has more information on this fascinating architectural style, including an interview with Freddy Mamani.

Photography by Yuri Segalerba