Concrete as a building material has been used at least as far back as the Roman Empire. In the modern age, the overuse of concrete in Soviet-style blockhouse construction – Brutalism – has tarnished its reputation, but lately the versatile material has enjoyed a revival in new construction and a reappraisal by architecture critics. We’ll “aggregate” some of concrete’s bests & worsts through history in these 15 examples.

Cementing a Legend

(images via: SiteBits and Roman Homes)

(images via: SiteBits and Roman Homes)

Concrete in its most basic form is made from mixing cement, pebbles & sand (aggregate) and water. The ancient Romans were known to have added horse hair, milk, animal fat and even blood to the mix. Odd perhaps but one can’t argue with the results: some of the Eternal City’s most enduring structures, such as the Coliseum, the Pantheon and thousands of miles of roadways owe their longevity to concrete.

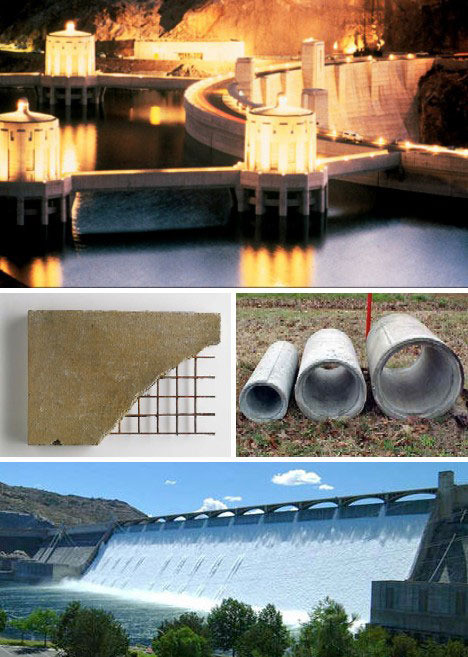

Dammed Concrete!

(images via: Only Vegas and DKimages)

(images via: Only Vegas and DKimages)

A number of technological advances in the 19th century, most notably the innovation of reinforced concrete in 1849, made the incredible 20th century construction boom possible. Mega projects leaped off drawing boards and into fruition. Concrete’s great strength and resistance to fracturing was put to good use in the Hoover and Grand Coulee dams built in the mid-1930s.

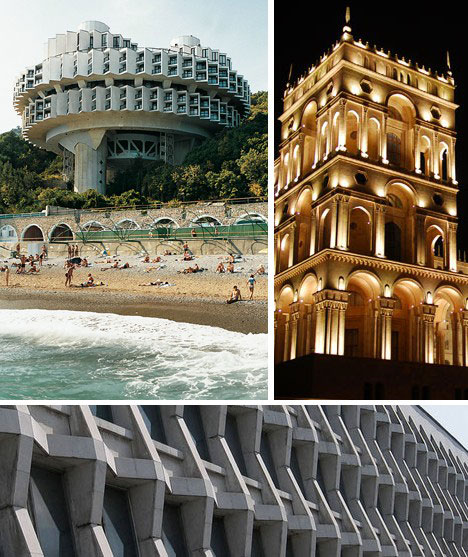

Soviet Concrete: The Good

(images via: Panoramio and Essays & Effluvia)

(images via: Panoramio and Essays & Effluvia)

Concrete was the ideal working material for Soviet central planners: it made possible the construction of huge buildings on a truly heroic scale. Surprisingly, it also facilitated some remarkably beautiful structures such as the Druzhba (Friendship) Sanitarium in Yalta, Ukraine (above left), designed by architect Igor Vasilevsky and completed in 1986.

Soviet Concrete: The Bad

(images via: Jorgen Stadje and Horizons Unlimited)

(images via: Jorgen Stadje and Horizons Unlimited)

Communism did much to give concrete a bad name. Though cheap, strong and easy to work with, so-called Soviet Concrete was often poorly formulated and little if any thought was given to style, especially when it came to residential construction. Used extensively throughout the former Eastern Bloc, shoddy concrete was often an accident waiting to happen and its use likely contributed to the huge death toll in the 1988 Spitak Earthquake in Armenia.

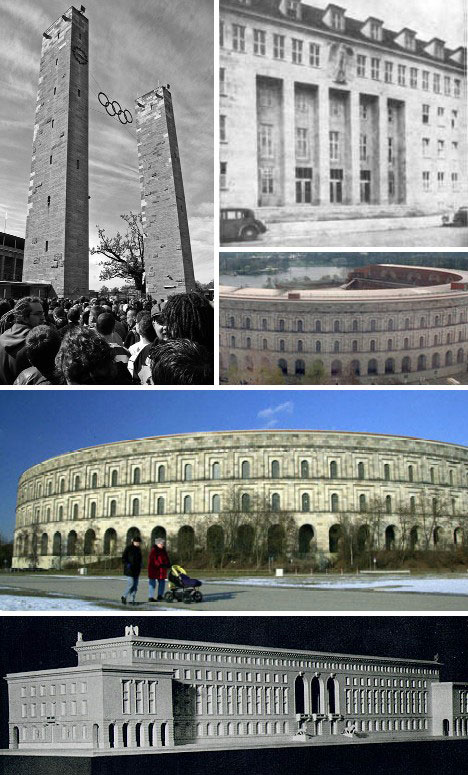

Nazi Concrete: The Ugly

(images via: Trek Earth and DW-World)

(images via: Trek Earth and DW-World)

Things weren’t any better at the opposite end of the political spectrum. Nazi propagandists, enthusiastically cheered on by Adolf Hitler, saw monumental buildings as an expression of political power and used concrete in prodigious quantities to bring their distorted imaginings to reality. Many of these buildings – brutalism in the true sense of the word – were bombed during World War II but some remain, including the 1936 Olympic Stadion and the never-finished Nuremberg Congress Hall. The latter was modeled after the Coliseum in Rome but was to be 25% larger.

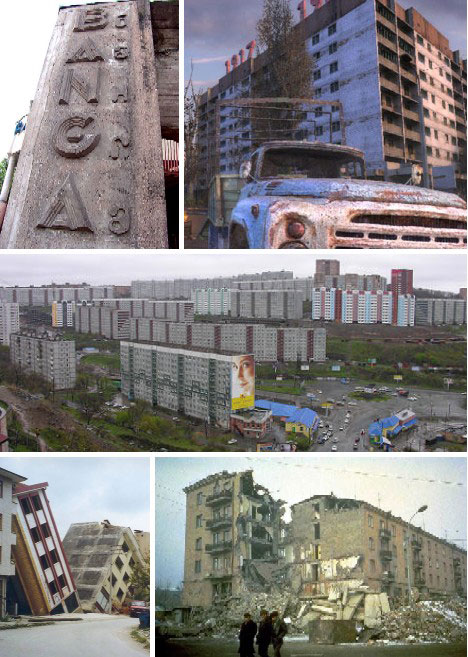

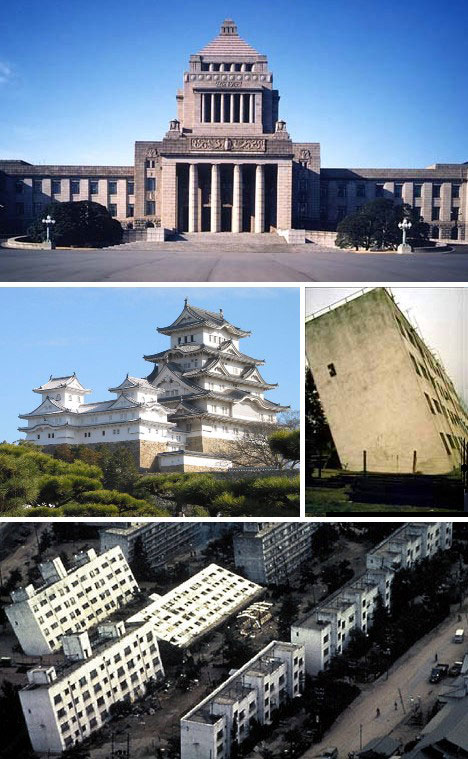

Concrete Goes East

(images via: Essential Architecture and The National Diet of Japan)

(images via: Essential Architecture and The National Diet of Japan)

Japan has had a lot of experience with concrete, having had to rebuild Tokyo after the Great Kanto earthquake of 1923 and, once again, after the devastating American bombing raids of 1945. Ferroconcrete (concrete reinforced with iron rebars) has not only allowed for quick reconstruction, it is adaptable enough to restore the look of structures many centuries old, like Japan’s medieval castles. On the other hand, the National Diet Building (Japan’s center of government, above top) looks as bleak and forbidding as some Soviet and Nazi structures. Reinforced concrete is also praised for its strength but Japan is one of the world’s most earthquake-prone countries. The images above, lower, show some concrete apartments in Niigata prefecture which were sheared right off their foundations during a massive 7.5 tremor in 1964.

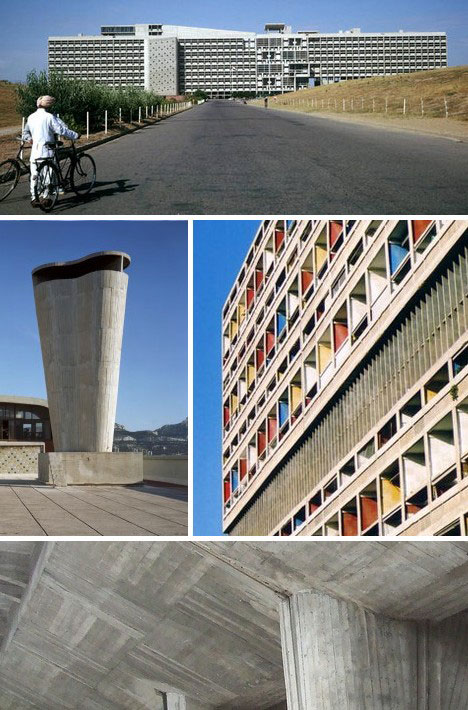

Rebuilding the World, Block by Block

(images via: Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery and Downtown Creator)

(images via: Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery and Downtown Creator)

Postwar planners had an interest in rebuilding faster, bigger and better than before – and concrete was just the right material for the job. Although many of the structures looked fresh and modern at first, it son became apparent that the raw, bare concrete structures (termed “beton brut”, French for “rough concrete”) lacked personality and promoted alienation. Famed architect Le Corbusier was one of the first to popularize the so-called Brutalist style, as can be seen above, top down: the 1953 Secretariat Building in Chandigarh, India, the 1947-52 Unite d’Habitation in Marseilles, France, and the massive underpinnings of the 1959 Berlin Unité d’Habitation.

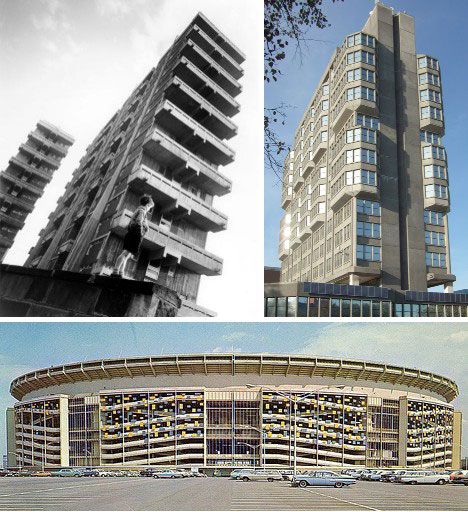

Brutally Yours

(images via: Architecture.com and Bobster1985)

(images via: Architecture.com and Bobster1985)

“Powerful as a silhouette, elevation and detail, but brutal as an environment.” This phrase captures the essence of Brutalism, characterized by strong horizontal and vertical planes while presenting a hulking, massive appearance of which the best thing that can be said is that it displays stability. The two towers shown above, top, were built in the 1950s (left) and 1966 (right) during the heyday of the Brutalist movement. New York’s Shea Stadium, shown here on the cover of the 1964 dedication brochure, is also classic Brutalist though the raw concrete is tempered by the pop-art colorful squares (later removed).

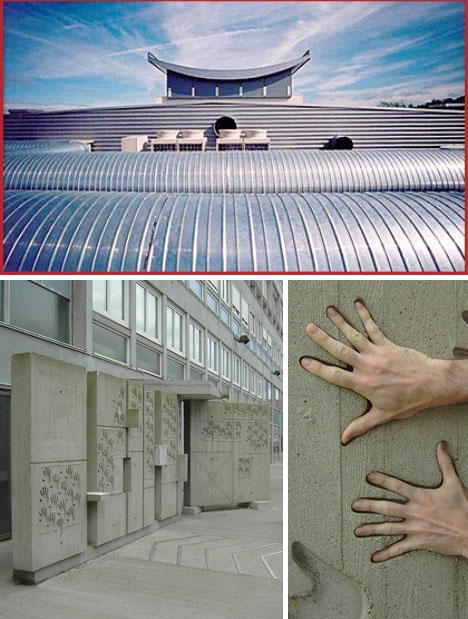

Brutality vs. Humanity

(images via: Operas France and L’esprit de l’escalier)

(images via: Operas France and L’esprit de l’escalier)

By the late 1960s, Brutalism was beginning to warm up a little as architects felt less pressure to throw up structures for the sake of speed. The Opéra de Saint-Étienne, completed in 1969, displays imprints of human hands set into its facade. The contrast between the organic curvaceousness of the handprints with bare concrete imprinted with the grain of its wooden supporting forms is jarring yet oddly welcoming.

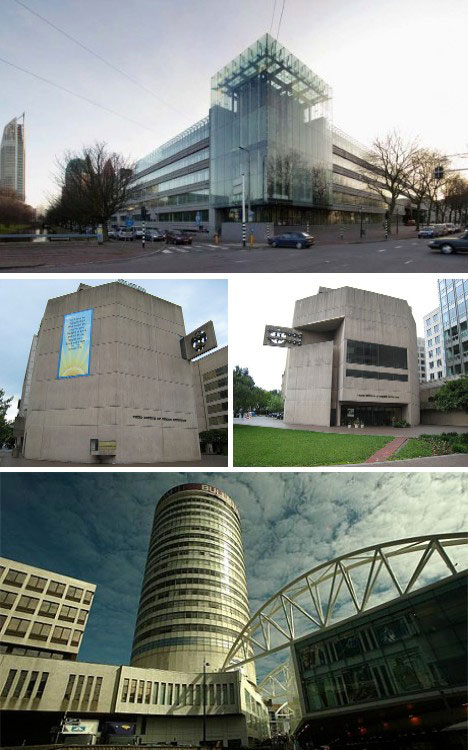

A Striking Beauty

(images via: Arplustest, Apartment Therapy and Guardian UK)

(images via: Arplustest, Apartment Therapy and Guardian UK)

Not all Brutalist architecture is “bad”, and some say all examples of the style has been tarred with the same brush. The examples above show a striking beauty that lifts them up from the confines of “the box they came in”. From top down: the recently renovated Ministry of Finance in The Hague, The Netherlands originally built in 1975, the 1971 Third Church of Christ, Scientist, in Washington DC, and the Bull Ring shopping center and revamped Rotunda apartments in Birmingham, UK.

Kinder, Gentler… Brutaler?

(images via: Arplustest, Darkmatter and Centre for the Aesthetic Revolution)

(images via: Arplustest, Darkmatter and Centre for the Aesthetic Revolution)

Brutalism – and the use of concrete in general – can produce a wide range of appealing, even delicate, organic forms. Take the shot (above, top left) taken at the Central Library at UC Irvine in Orange County. Repetitive arches of formed, reinforced concrete glow in waves or orange, reminding one of the iconic RSS symbol writ extra large! Recently efforts are being made to soften the look of existing Brutalist buildings by sandblasting the rough concrete and applying stucco, paint or colorful appliques. Designed with the future in mind, Brutalist structures still look “new” and like many of us, often look better after a makeover.

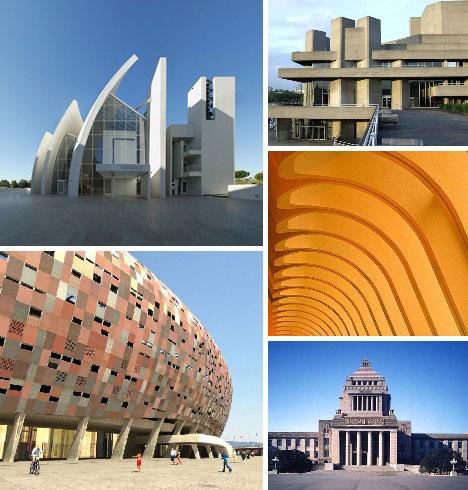

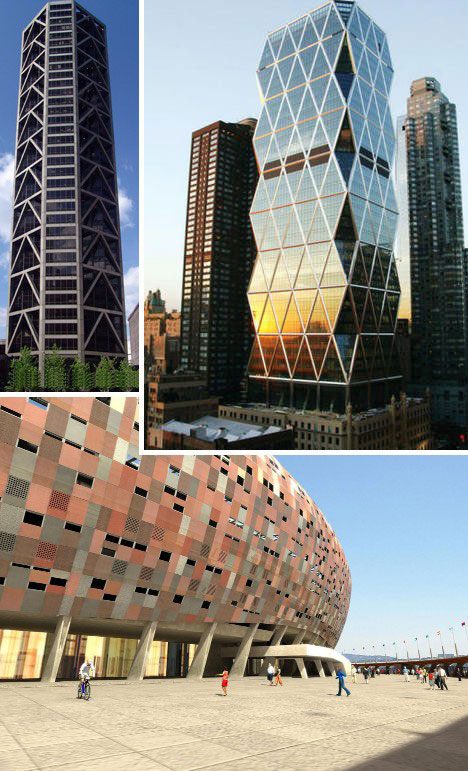

Post-Brutalism in Concrete Terms

(image via: Glass, Steel & Stone)

(image via: Glass, Steel & Stone)

Most chroniclers list 1975 as marking the end of the Brutalist architectural style, to be followed by Structural Expressionism (or Post-Modernism) and Deconstructivism. The former is characterized by a high-tech look achieved in many cases by exposing structural details such as metal beams and buttresses. Expressing the structure, as it were. Though concrete is still a major component in these buildings, it plays a supporting role and does not overwhelm the visual senses as in Brutalism. An early example is 1976’s 1 US Bank Plaza located in St. Louis (above left) while the Soccer City stadium currently under construction for the 2010 World Cup in Africa (above, bottom) uses fibre-C glassfibre concrete panels on its wraparound facade.

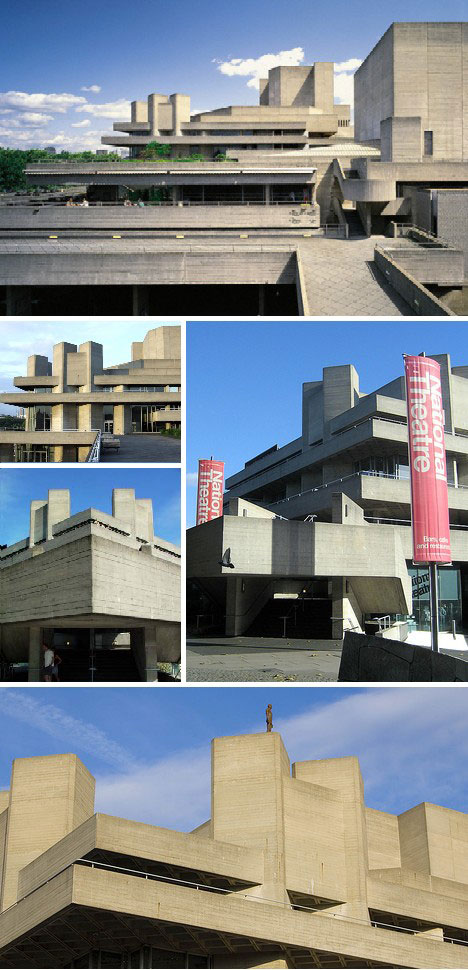

The Brute is Back

(images via: Nationaltheatre.org and Hobbes vs Boyle)

(images via: Nationaltheatre.org and Hobbes vs Boyle)

It seems that both the public and the architectural community is becoming bored with the curvilinear, glass & steel Deconstructivist style that burst onto the scene in the late 1980s and may be ready for a return to Brutalism. This trend, called “New Brutalism”, has been noted in Israel where there is an innate desire for stability and security. Economics also play a part as formed concrete is a cheaper building material that still allows a very wide range of design flexibility. The Royal National Theatre in London, England, opened in 1988 to mixed reviews, most notoriously from Prince Charles who described it as “a clever way of building a nuclear power station in the middle of London without anyone objecting.”

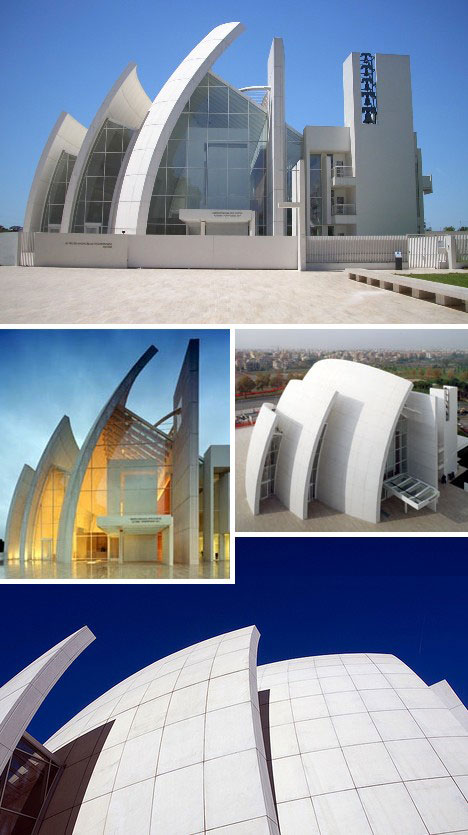

Stone Immaculate

(images via: Mimoa and Daniela Brocca)

(images via: Mimoa and Daniela Brocca)

Concrete will continue to be essential in creating the buildings of the future, and new ways of using this ancient material are already emerging. One of the most engaging is the exquisite Jubilee Church, also known as the Parisch Church of Dio Padre Misericordioso in Rome, Italy. Designed by Richard Meier and completed in the year 2000, the church features a trio of soaring concrete arches which represent the Holy Trinity.

This video by Roberto De Angelis is a 3D-animation of the Jubilee Church composed as the highlight of his design thesis:

Monumentalist Miniatures

(images via: Apartment Therapy and Mollaspace)

(images via: Apartment Therapy and Mollaspace)

To end on a light note we present these miniature concrete buildings from Pull+Push, designed by Nobuhiro Sato. Crafted to scale yet charmingly tiny, these cute blockhouses feature balconies, stairways, even chimneys that smoke – when you use the base as an incense pot or an ashtray. Slightly larger models make perfect planters for those who desire their very own microcosmic concrete jungle.