(Check out our complete collection of Green Art, Design and Technology.)

Imagine the world in 2050 with almost 80% of the planet’s population living in urban centers and our fruit, vegetables and even animals are grown in … skyscrapers? One man’s vision has sparked a series of designs leading closer and closer to what will be the first real-life vertical urban farm in Las Vegas, Nevada of all places. Here are five of these remarkable architectural designs for sustainable (and stylish) urban farm towers that may revolutionize agriculture as we know it. In the long run such structures may not only provide food for hundreds of thousands of people per building but they will also relieve much of the burden on other flat landscapes where fewer and fewer usable growing spaces exist.

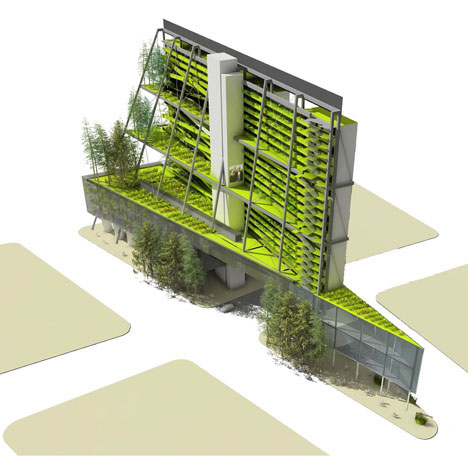

One of the first designs of its kind, the compelling vertical farm project above was undertaken by Chris Jacobs in cooperation with the grandfather of skyscraper farm concepts: Dr. Dickson Despommier of Columbia University. His ideal: all-in-one eco-towers would be actually produce more energy, water (via condensation/purification) and food than their occupants would consume. His mission: to gather architects, engineers, economists and urban planners to develop a sustainable and high-tech wonder of ecological engineering.

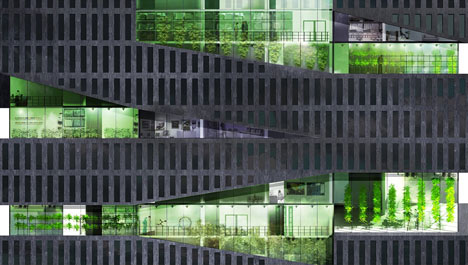

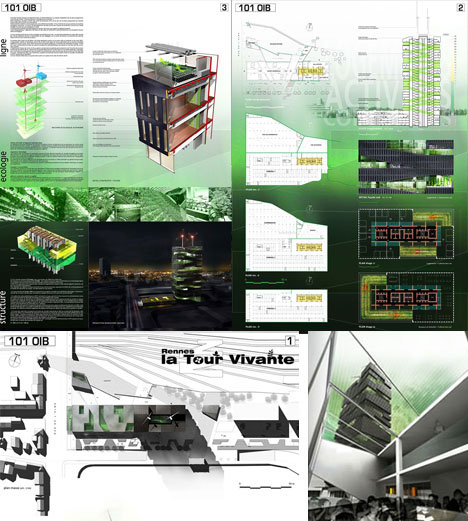

Architect Pierre Sartoux of Atelier SOA has gone a step further and put some serious design talent behind his proposal for a vertical farming skyscraper. A light-shading skin wraps around the structure and opens to admit sunlight at particular locations for various functional (and aesthetic) purposes. The building’s air, heating and cooling systems are wind-driven and circulate oxygen and carbon dioxide between growing and living spaces. The simple but reinforced structure is designed to handle additional dead loads from the weight of growing floors and also serve to make the entire building more durable (and thus sustainable).

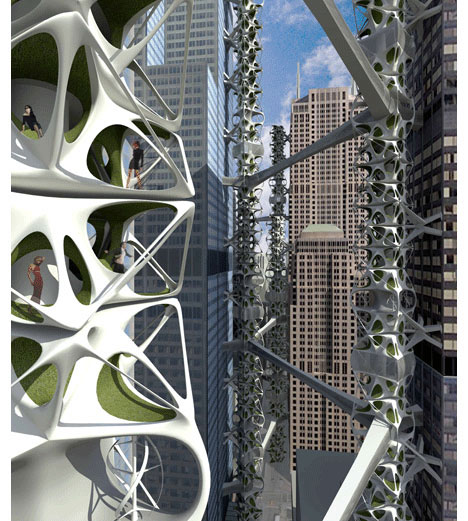

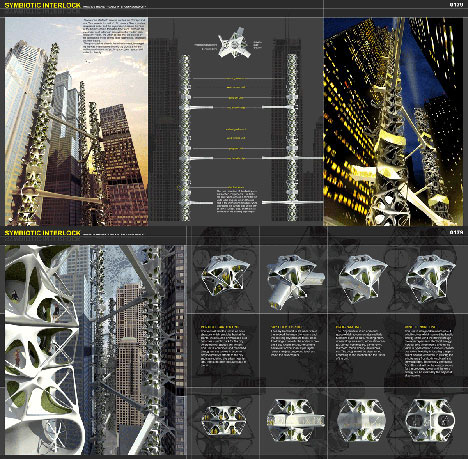

Given that most urban cores are already densely built, one designer has proposed an auxiliary series of structures to be attached to existing structures in downtown areas. These modular constructions would provide garden and recreation spaces for residents as well as light and air filters for the adjacent buildings. In some cases, these retrofits could even provide structural stability to aged buildings and prevent the need to tear them down. Architecturally, these modular units stand out and add another layer to the visual hierarchy of the cities around them.

The Pacific Northwest regional architecture firm Mithun developed a compelling vertical farm building design to incorporate various green building strategies in a mixed-use residential and commercial complexdesigned for downtown Seattle. The concept? Simply put, the structure is designed as a kind of built organism – completely self-sufficient and adaptive to its surroundings. The design includes water and energy self-sufficiency from rainwater and gray water collection and reuse, solar cells, vegetable and grain growing spaces and even a chicken farm – all built on a small-footprint downtown urban lot.

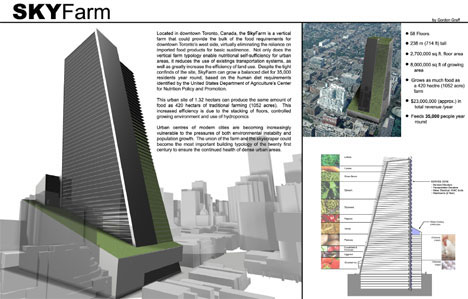

Architect Gordon Graff may succeed in the more green and progressive city of Toronto with his plans for a sky farm with 48 floors and millions of square feet of floor space (and even more growing space). This building, if constructed, will be able to feed tens of thousands of people per year. Best of all, particularly in Canada, the success of the building’s crops isn’t contingent upon climactic conditions. As an architectural and urban design gesture this structure both fits into the city skyline and differentiates itself with simple layers of green.

Depending on your point of view Las Vegas might be the first or it could be the last place you’d imagine the 30-story world’s first vertical farm. Of course, the food isn’t going to feed the famished masses. It will instead grace the dinner plates of Vegas tourists at local casinos and hotels. Still, as a prototype it has a lot of potential to generate further buzz and interest that could in turn lead to future projects. If the model proves both profitable and sustainable (always the best combination) it will likely (and hopefully) be the first of many.