10 years into the 21st century, film photography has been almost completely written off as obsolete, with even amateur photographers ditching traditional cameras for the crispness and convenience of digital. But there’s something missing from today’s almost-too-perfect pictures: that indescribable magic that film can have. All the Photoshop filters and iPhone apps in the world can’t quite approximate the effects of low-tech photography taken with pinhole, Polaroid and Holga cameras.

Pinhole Photography

(image via: xiao shan)

The concept of camera obscura may be older than we know, with observations of the way light passes through a hole and projects an image onto a surface going back to Chinese philosopher Mo-Ti in the 5th century BCE. But once the first pinhole camera took advantage of this phenomenon along with the development of chemical photography, the result was permanent photographs that have an infinite depth of field and often an eerie, otherworldly feel to them.

(images via: nhung dang)

Considering how expensive and complicated many modern digital cameras are, it’s refreshing to realize that essentially, a camera is just a dark box with a hole, a shutter and some photo paper or film. Tea tins, oatmeal tubs, paint cans, pumpkins – all of these things can be turned into a camera with a needle, some tape and possibly black spray paint. Corbis even offers downloadable templates to create your own colorful camera from paper.

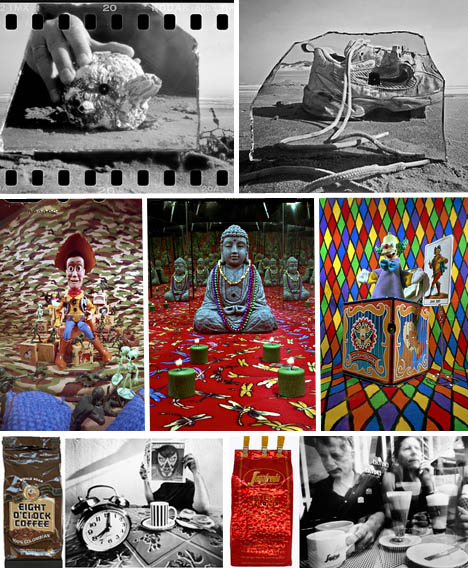

(images via: ralph howell)

These pinhole cameras are sometimes fascinating and beautiful objects in themselves, so it’s no wonder that photographer Ralph Howell decided to allow his creations to take their own self-portraits using mirrors. Conch shells, shoes, coffee bags, plastic Buddhas and a Krusty the Clown jack-in-the-box are just a few of Howell’s chosen objects.

“I perceive the pinhole as a “seeing eye”, a single hole sieve that filters information,” Howell says in his artist statement. “The human mind has the capacity to perceive and form perceptions into thought and image and to then reflect upon both itself and its products. This concept is the basis for the Mirror Reflection series: the pinhole camera’s “self-portrait” is an image of creator reflecting on its creation. I am also concerned with the pinhole camera-as-object, as a ‘ready-made’ – the pinhole camera being as important as the images it creates.”

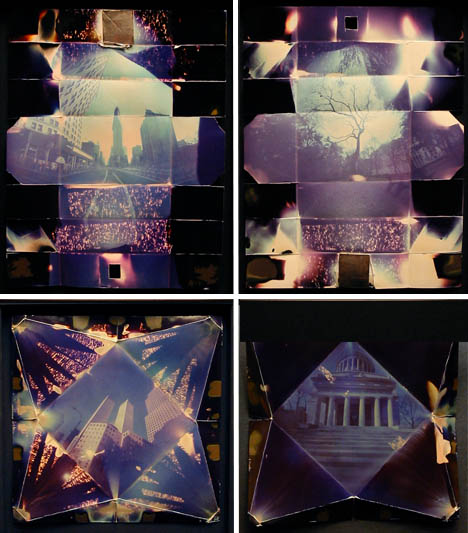

(images via: papercams)

It doesn’t get much simpler than this: Thomas Hudson Reeve’s pinhole camera is made out of photo paper itself. The photo paper, fitted with a pinhole in a brass plate, creates a direct positive image made complex and absolutely unique by the manner in which the paper is folded. “Like a salad bowl made of lettuce leaf, and consumed with the meal, the camera doesn’t exist after its utility is fulfilled. There is no machine. It is more of an arrangement than a thing,” Reeve says on his website.

Holga Photography

(image via: cherie)

What is it that gives amateur 1970s and ‘80s photographs that signature diffused, dreamlike look? It has a lot to do with cheaply made camera bodies and flawed plastic lenses, both of which combine to allow little streaks of light in, create subtle vignetting and give parts of the image a blurred or grainy look. To most photographers, these qualities are undesirable – but when you give in to them, they can conspire to create images that just can’t be replicated any other way.

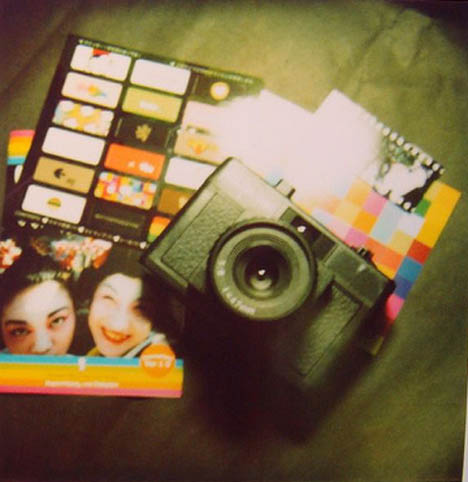

(images via: vick the viking)

Enter the Holga: a piece of plastic made-in-China junk that takes unbelievably magical photos. The shoddy construction of this medium-format toy camera is actually what makes the images taken with it so special, so completely one-of-a-kind. No one Holga takes pictures quite like any other. Since its debut in Hong Kong in 1982, the clunky Holga has amassed a cult following addicted to the rush of constantly being surprised by what the camera produces. That’s part of the fun: the mystery of the final result.

(images via: boliston)

It’s the simplicity of this camera that allows for so much creative freedom. An extremely basic film advancing knob gives the user total control over each frame, easily allowing multiple exposures, and the optional bulb mode permits long exposures. Many people modify their Holgas to increase or decrease light leaks, add to the number of apertures available and even take different kinds of film including 35mm and Polaroid. As with practically any other camera, filters and the type of film used also alter the results.

(images via: jelleS)

Holga photographers encourage literally ‘shooting from the hip’ to add to the spontaneity of the results, and why not – the viewfinder doesn’t give you an accurate idea of what the photo is going to look like, anyway.

(images via: lomo-cam)

Polaroid Photography

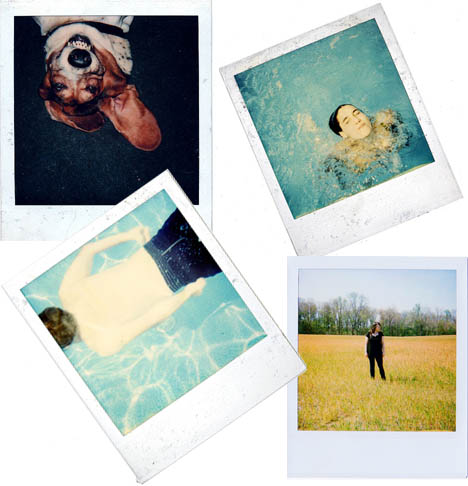

(images via: lepiaf.geo)

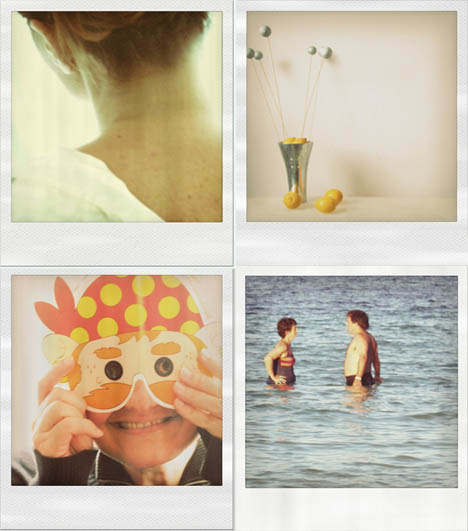

The Polaroid camera changed photography forever, but its particular quirky brand of instant photos was a relatively short-lived precursor to quick-and-easy digital photos. Some say digital photography killed Polaroid, and indeed, the company stopped production of both its cameras and its film – the last of which expired in October of last year.

(images via: brainware3000)

One form of instant gratification may have been exchanged for another, but many lament the loss. Jason Bitner, author of the book Found Polaroids, calls the medium “instant nostalgia–framed and faded, a picture that already looked decades old.”

(images via: sicoactiva)

But all isn’t lost for Polaroid aficionados – “a new chapter of analog Instant Photography” is coming in the form of The Impossible Project, which leased a former Polaroid factory in Holland and is set to debut their version of the beloved classic this month.