How different would the world be today if the Bible contained a book that advocates free love? If we had access to the other two-thirds of the writings of Aristotle, one of the most influential human beings of all time? What could we have learned from the thousands of texts that were contained within the Library of Alexandria? Unfortunately, we’ll never know, because we don’t even know exactly what these works said. Missing, destroyed or in one case, never even written, these 7 lost wonders of the written word will likely always remain a mystery.

William Shakespeare’s Cardenio

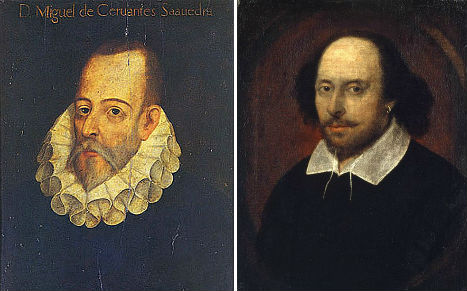

(image via: wikimedia commons)

Shakespeare might just be the most celebrated author and playwright of all time, with his plays performed by amateur and professional theaters alike all over the world nearly four centuries after his death. But lost to history are not one but two of Shakespeare’s works, and we’ll never know quite how well they stack up to the rest of his oeuvre. The first, ‘Love’s Labours Won’, is possibly a sequel to his famous work ‘Love’s Labours Lost’; it seems to have been published in 1603, but no copies survive.

More interesting, however, is another lost work that brings together two of that era’s greatest talents. ‘Cardenio‘ is thought to be one of the most valuable lost literary works. Though we know very little about it, aside from the fact that it was performed before King James I in May and June of 1613, it is apparent that it was based on the work of another great writer: Miguel de Cervantes. ‘Cardenio’ was the name of a major character from Cervantes’ ‘Don Quixote.’

No written record of ‘Cardenio’ remains, but so beloved is Shakespeare’s talent that there have been numerous attempts to creatively imagine what they play might have been about. In 2008, scholar Stephen Greenblatt and playwright Charles Mee collaborated to produce a re-imagined ‘Cardenio’ at Harvard’s American Repertory Theater.

Plato’s Hermocrates

(image via: wikimedia commons)

Technically, this one’s just hypothetical. But rumor has it that Greek philosopher Plato planned to write a third dialogue in his unified field trilogy. Hermocrates would have been a follow-up to Timaeus and Critias, both of which detail the discussions between some of history’s greatest thinkers. Given that Critias stopped in mid-sentence, we can only assume that he never even started writing Hermocrates.

Hermocrates was a historical figure, almost certainly the Syracusan politician and general who is mentioned in Critias. Says historian F.M. Conford, “Since the dialogue that was to bear his name was never written, we can only guess why Plato chose him. It is curious to reflect that, while Critias is to recount how the prehistoric Athens of nine thousand years ago had repelled the invasion from Atlantis and saved the Mediterranean peoples from slavery, Hermocrates would be remembered by the Athenians as the man who had repulsed their own greatest effort at imperialist expansion.”

Two-Thirds of Aristotle’s Writing

(image via: wikimedia commons)

The writings of Greek philosopher Aristotle helped form the basis of Western philosophy as well as scholarship on a wide range of topics including physics, metaphysics, poetry, theater, politics, government, ethics, biology and zoology. His works include the earliest-known formal study of logic. So it’s probably not an understatement to say that human thinking could have been profoundly affected by the large volume of Aristotle’s writings that are now lost.

What we do have of Aristotle’s writings is enough to demonstrate a highly prolific lifetime of critical study, so it’s hard to imagine that we have only read about one-third of it. He remains one of the most influential people to have ever lived.

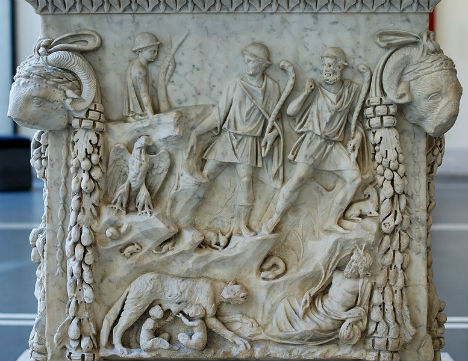

Ab Urbe Condita Libri by Livy

(image via: wikimedia commons)

A monumental history of Rome written sometime between 27 and 25 BC, Ab Urbe Condita Libri covers the time between the period before the city’s founding in 753 BC all the way to the reign of the emperor Augustus in 9 BC. Historian Titus Livius (Livy) gathered this information into 142 books in a mixture of chronology and narrative. Only about 25% of the history survives; the manuscript was damaged in the 5th century CE and some of it was never preserved in the first place. With the volume of writing that Livy did on so many centuries of history, there’s no telling how much detail we could have learned about this once-great civilization.

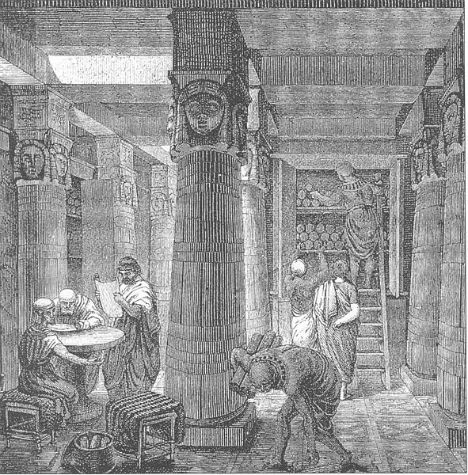

The Entire Collection of the Library of Alexandria

(image via: wikimedia commons)

The largest and most significant library of the ancient world, the Library of Alexandria in Egypt was a major center of scholarship from the time it was built in the 3rd century BC until the Roman conquest of Egypt in 30 BC. The library is thought to have been initially organized by Demetrius of Phaleron, a student of Aristotle, and it included gardens and a dining room in addition to reading rooms, meeting rooms and lecture halls. It was the first known library to gather a collection of books from beyond its country’s borders, aiming to collect all of the world’s knowledge.

Nobody knows quite how large the collection was. We do know that it functioned as a research institute for the great thinkers of the time including Euclid and Archimedes, with rooms dedicated to the study of astronomy, anatomy and other academic subjects.

Plutarch wrote that Julius Caesar ‘accidentally’ burned the library down during a visit to Alexandria in 48 BC when he set fire to his own ships. The salvaged materials, which were transferred to a new library, could have been destroyed at various points throughout history including the Muslim conquest in 642 CE.

The Book of the Wars of the Lord

(image via: wikimedia commons)

Most modern Christians tend to think of the Bible as a handbook to life – but what about all of the parts that were taken out over time? The Book of the Wars of the Lord is among the non-canonical books referenced by the Bible which are now completely lost. Academics believe that it might be a collection of victory songs or poems, while some suggest that it may be a military history. It’s cited in the medieval Book of Jasher Chapter 90:48 as being written by Moses, Joshua and the children of Israel.

That single mention – the mere listing of its name and authors – is all that we know of it. It may or may not have been suppressed by early Christian leaders and church fathers, who seem to have removed some writings from original biblical texts.

The Gospel of Eve

(image via: wikimedia commons)

Among the New Testament apocrypha – Biblical books that are not considered ‘canonical’ – is the Gospel of Eve. All that we know of it comes from a few quotations by Epiphanius, a 4th century CE church father who complained that the Borborites, a Gnostic sect, used it as a license to practice ‘free love’. Apparently, in translation of the Gospel of Eve, the Borborites practiced coitus interruptus and eating semen as a religious act.

Epiphanius quoted the following line from the Gospel of Eve, interpreting it to be about semen:

“I stood on a lofty mountain and saw a gigantic man, and another, a dwarf; and I heard as it were a voice of thunder, and drew nigh for to hear; and He spake unto me and said: I am thou, and thou art I; and wheresoever thou mayest be I am there. In all am I scattered [that is, the Logos as seed or “members”], and whencesoever thou willest, thou gatherest Me; and gathering Me, thou gatherest Thyself.”

He also noted that another line seemed to be about the menstrual cycle:

“I saw a tree bearing twelve manner of fruits every year, and he said unto me, This is the tree of life …”

This is dirty stuff for the bible, and Epiphanius wanted no part of it. He said of the Gospel of Perfection – which is believed by some to be the same as the Gospel of Eve – “”Some of them (i.e. of the Gnostics) there are who vaunt the possession of a certain fictitious, far-fetched poem which they call the Gospel of Perfection, whereas it is not a Gospel, but the perfection of misery. For the bitterness of death is consummated in that production of the devil. Others without shame boast their Gospel of Eve.”