Breaking down one of the most difficult types of trash, this incredible working incubator turns sterilized plastic remnants into nutritional biomass humans can consume and digest, in short: food. Texture, taste and flavor depend upon the strain of fungus, but reportedly can be quite strong as well as quite sweet.

Livin Studio, an Austrian design group known for innovative work on insect farms, has built a working model of this growth sphere (dubbed the Fungi Mutarium) that takes parts of mushrooms usually left uneaten and grows them into fresh snacks.

From the creators: “We were working with fungi named Schizophyllum Commune and Pleurotus Ostreatus. They are found throughout the world and can be seen on a wide range of timbers and many other plant-based substrates virtually anywhere in Europe, Asia, Africa, the Americas and Australia. Next to the property of digesting toxic waste materials, they are also commonly eaten. As the fungi break down the plastic ingredients and don’t store them, like they do with metals, they are edible.”

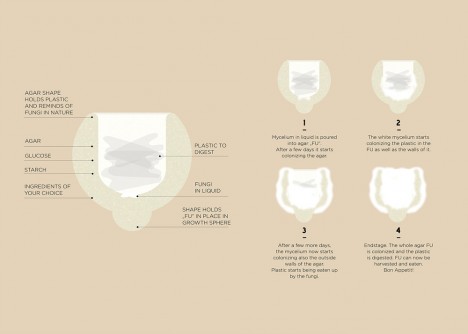

In terms of the process, “Fungi Mutarium is a prototype that grows edible fungal biomass, mainly the mycelium, as a novel food product. Fungi is cultivated on specifically designed agar shapes that the designers called FU. Agar is a seaweed based gelatin substitute and acts, mixed with starch and sugar, as a nutrient base for the fungi. The FUs are filled with plastics. The fungi is then inserted, it digests the plastic and overgrows the whole substrate. The shape of the FU is designed so that it holds the plastic and to offer the fungi a lot of surface to grow on. “

For now, the digestion is a relatively slow process, taking up to a few months for a set of cultures to fully mature, but by the standards of plastic biodegrading in nature this is still an extraordinary feat. The team continues to work with university researchers to make the process faster and more efficient. “Scientific research has shown that fungi can degrade toxic and persistent waste materials such as plastics, converting them into edible fungal biomass.”

This novel application comes just a few years after a group of Yale students discovered a species of fungi on a trip to Ecuador as part of a Rainforest Expedition and Labratory led by a molecular biochemist (with findings subsequently published in the Journal of Applied and Environmental Biology). Even in the absence of light and air, the species they examined thrived in landfill environments, suggesting potential near-future and larger-scale solution for existing waste sites as well.