A bustling car-filled street by day and a 1,500-foot pedestrian promenade on weekend nights, Sai Yeung Choi Street South in the dense neighborhood of Mong Kok was the stage upon which urban life in Hong Kong played out – markets, music, dancing, protests, parties. Clashes with police. Noise. So much noise, in fact, that after 1,200 complaints in a single year, the district council decided to end the street’s 18-year run as a part time pedestrian zone and reopen it to vehicular traffic 24/7. What will this mean for a city where public transit accounts for 90 percent of daily passenger trips, yet infrastructure revolves around cars?

Some Hong Kong residents see the Mong Kok street’s closure as emblematic of the cultural battle between everyday transit-riding urbanites who embrace city life and everything that comes along with it (including noise) and ‘elites’ who flood cities from elsewhere and expect to change how they operate to better fit their own needs. This might sound familiar to, say, San Franciscans. Walkability is a crucial quality-of-life factor for many city dwellers, but it remains in tension with both car culture and a general lack of affordability. So why do some major pedestrian zones in big cities flourish while others fail?

A History of Mixed Success

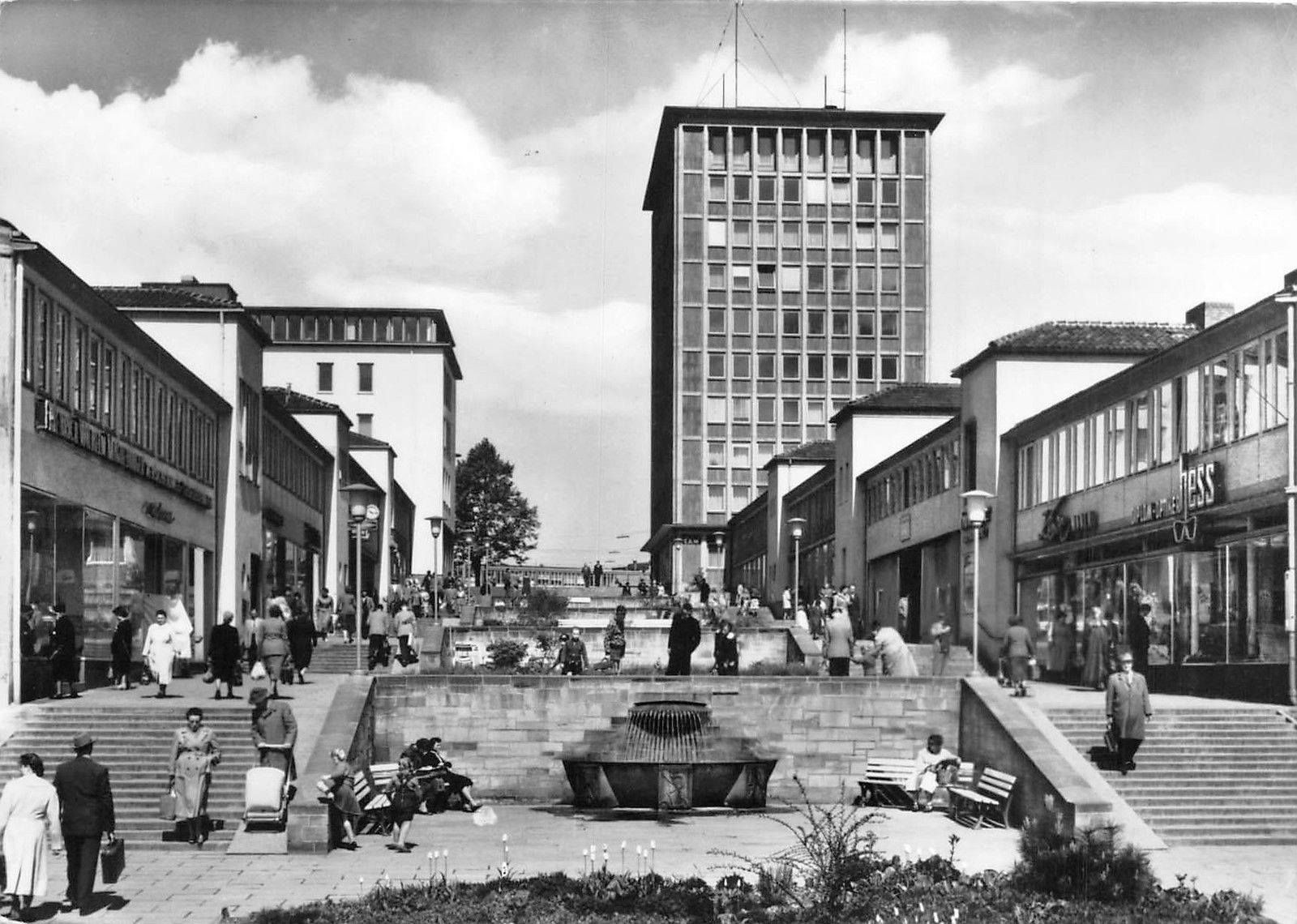

The pedestrian mall as we know it today was born in the German city of Kassel soon after the end of World War II. British bombers had leveled 80 percent of the city. City planners tasked with rebuilding decided it was the perfect opportunity to re-orient the old town’s streets to create a direct connection from the center square to the main railway station and create a distinct shopping district where pedestrians could stroll along the streets without worrying about cars.

The fountain-filled square, called Treppenstrasse, was soon copied by other German cities, and the idea spread throughout Europe. Meanwhile, in America, the first pedestrian mall opened in 1959 in Kalamazoo, Michigan and multiplied in a similar fashion, all in the hope of reviving depressed downtown areas.

What these pedestrian zones were essentially trying to recapture – in a shiny new package befitting the 1950s – was the charm of meandering medieval streets no more than a few meters wide. Crucially, these often cobblestoned streets were built at a human scale, designed to accommodate people strolling along with carts and horses rather than rows of parked vehicles and 48-foot-long semi trucks. That’s rarely the case now, especially when attempting to retrofit spaces built for cars into pedestrian-friendly areas that attract a lot of foot traffic and, ultimately, spending.

There was one major problem with ‘50s pedestrian malls right off the bat. At the time, few people lived downtown. As soon as workers went home for the day, the promenades were abandoned. It would be decades before populations began to shift toward urban centers en masse, and in the meantime, the pedestrian mall experiment was declared a failure. Fewer than 15 percent of the malls that opened during that era remain in place today.

This process of pedestrianizing certain blocks and then reopening them to traffic continued throughout the 1970s, ‘80s and ’90s, by which time shoppers were demanding plenty of free parking and covered spaces. Walking outdoors to shop and dine was old fashioned; the suburban mall reigned supreme.

Chicago’s State Street pedestrian mall closed after 17 years in 1996 due to a drop in commercial activity. In Buffalo, New York, there weren’t enough people spending time downtown to support its pedestrian zone. In Sacramento, K Street went from a vibrant destination to a wasteland to a bustling pedestrian zone and back to a wasteland before the city ripped out the pedestrian-friendly infrastructure and reopened it to traffic in 2011 – only for locals to call for reversing the decision yet again, just five years later.

But what about the ones that work? New York City temporarily closed a 2.5 acre-section of Times Square to vehicular traffic for safety reasons, but it became so popular with pedestrians, the city made it a permanent feature and even had the architecture firm Snøhetta redesign it. Denver’s 16th street mall is thriving, as is Miami’s Lincoln Road Mall. Smaller college towns like Charlottesville, Iowa City and Madison have maintained popular pedestrian zones as crucial parts of their identities. In Europe, the cities of London, Paris, Oslo, Madrid, Milan, Dublin and Stockholm all have plans to create or expand significant car-free areas.

Walkability Requires Careful Planning – And Greater Equality

From all these failures and successes, it seems like the keys to making cities more walkable long-term are tailoring the scale and design of pedestrian zones to the setting, expecting roughly 15-year cycles of changing trends, accommodating businesses with features like early morning loading zones, figuring out where all the vehicular traffic will go instead to avoid worsening congestion and standing firm in commitment to reducing car usage in the area. That last point might just be the hardest one to tackle.

Some shoppers would rather give up on trying to access downtown areas due to a lack of parking than ride the bus instead, and as long as city planners continue to build massive parking garages, urban streets will remain snarled. Pedestrian zones must be integrated with public transit, taking the pressure off the streets and allowing equitable access. By many accounts, we’re moving toward an era in which car sharing will vastly reduce the number of vehicles on the roads, so we might as well begin planning for it now.

Closing certain blocks to vehicular traffic part-time, like Austin’s Sixth Street, could be a convenient workaround for many cities, or at least a way to test the waters. But that brings us back to Mong Kok, which could set a precedent for the closure of Hong Kong’s other pedestrian zones due to noise complaints amidst worsening air quality from automobile emissions. Licensing systems for vendors and performers could help, but the greater problem remains the fact that Hong Kong has begun to prioritize the needs of drivers over those of the vast majority of the population.

If we want thriving cities where people actually want to congregate, walk around and spend money, we have to preserve their historic character, cultural traditions and mix of income levels. That means addressing inequality directly and limiting the influence of wealthy residents who try to sweep evidence of that inequality under the rug, like homelessness in San Francisco.

Beneath the revival of big cities around the world is a deep economic rift that makes it hard for service workers, teachers, nurses and firefighters to live in the cities where they work, let alone shop. The urban tides might pull the affluent back out into the suburbs before long, anyway, so our cities should be designed to thrive with or without them.

Top image: Times Square pedestrian redesign by Snøhetta