A material once seen as a breakthrough innovation that could benefit the environment by replacing animal products now litters the Earth to the tune of approximately 6.3 billion metric tons, most of it in the world’s oceans. Forty percent of that plastic is single-use packaging.

While recycling might seem like the most obvious way to deal with the problem, the fact is, less than a fifth of all plastic is recycled globally – and even once it’s recycled, plastic typically just degrades into smaller pieces that are harder than ever to clean up. The smallest particles discovered in new research measure about the width of a human hair, small enough to penetrate membranes in the gut and bloodstream. We still don’t know what effects these contaminants have on our health, but it’s clear that they’re harming and killing marine life and other animals that accidentally consume them.

In a world accustomed to convenience and disposability, scaling back the use of plastics seems virtually impossible. That’s why the key to finding a way out of this mess might lie with products that function a lot like plastic, but behave entirely differently when their life cycle meets an end, whether they’re used for beverages or buildings.

Edible Options

Single-use plastics are manufactured for a fleeting purpose, maybe an hour or two protecting your beverage from spills or a few moments of swabbing cotton over your skin. A lot of these items are used for hygienic reasons – like a pair of disposable gloves or the packaging that keeps certain items clean as they’re shipped and displayed on store shelves. Most of them can’t be recycled at existing facilities. But what if they were able to serve the purpose they’re made for, and then practically disappear before our eyes? A host of promising new plastic alternatives made of organic materials are able to do just that.

Plentiful and sometimes even edible, seaweed might just become the packaging of choice for food and beverage uses, cosmetics and other applications. It’s cheap, easy to harvest and doesn’t require fresh water or fertilizer to grow, and can biodegrade in soil in less than six weeks. Seaweed beds are also natural carbon sinks, de-acidifying water. Different varieties of seaweed have different properties that make them ideal for one purpose or another, like flexible red seaweed for disposable plates and cups or agar for clear, jelly-like edible pouches.

Biocompatible Materials for Medical Applications

Some bioplastics might even have a future in hospitals for tissue engineering or suturing wounds. A material called “Shrilk” comes from the wings and outer skeletons of arthropods like crustaceans, spiders, beetles and caterpillars, which are made up of protein and a polysaccharide polymer called chitin arranged in a plywood-like structure. It’s translucent, resilient, pliable and strong. Shrilk could be used to create everything from garbage bags, diapers and packaging to scaffolds for tissue regeneration or growing organs for transplants in laboratories.

Other forms of bioplastics made from chitin can be mixed with cellulose from wood or cotton to create environmentally friendly barrier coatings for food, water-resistant paper, ceiling tiles and wallboards. No living creatures have to be harmed to produce them, either, since insects naturally shed their exoskeletons and humans produce mountains of discarded lobster, crab and shrimp shells after consuming them.

The University of Bath found that biodegradable plastics can be made using sugar and carbon dioxide, too, and it’s cheap and easy to produce using low pressures and room temperature process. The resulting material is strong, transparent and scratch-resistant and can be biodegraded back into carbon dioxide and sugar using enzymes from soil bacteria. Like plastics made from chitin, this bioplastic is bio-compatible and can safely be used for tissue engineering.

Made of tiny plant fibers, nanocellulose is also technically edible – though it probably doesn’t taste all that great. Sourced either from forestry or agricultural waste products, it’s stronger than steel per weight and stronger than the Kevlar that’s used in bulletproof vests since the fibers stick together into small, solid structures. When it’s broken down into nanocrystals with the help of strong acids, it can be made transparent and applied to surfaces to smooth and strengthen them, creating a better oxygen barrier than plastic. It’s especially well-suited to flexible electronic components, bone regeneration and wound healing.

Organic Materials in Plant-Based Binders

One of the biggest concerns about replacing plastic is the fact that it’s currently so cheap to produce. Can any other material quickly step in and take its place using the same manufacturing equipment? It turns out, the answer to that question is yes. Sulapac is a material made from FSC-certified wood and natural binders, and it has plastic-like properties while being totally biodegradable and leaving no micro plastics behind. Sulapac products are water-, oil- and oxygen-resistant and can be produced on most existing production lines, so companies can instantly switch from their current plastic materials to a sustainable alternative.

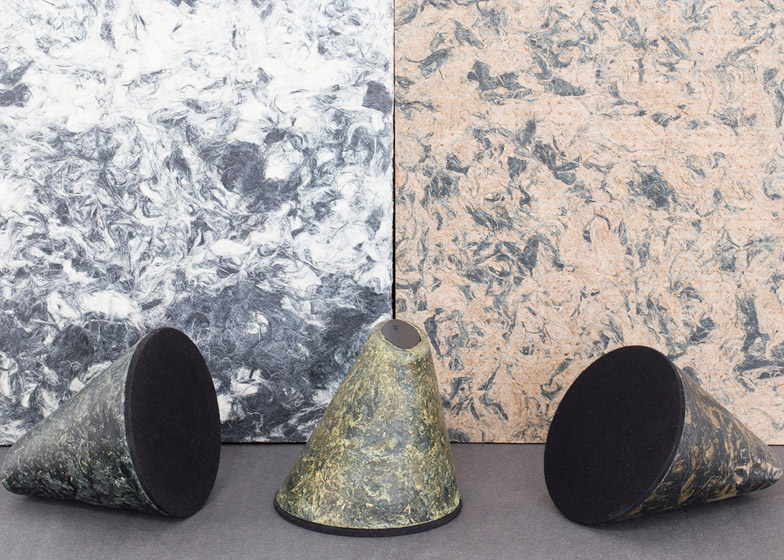

Even cow’s milk can be made into a sort of plastic. Casein plastic, made of milk proteins, is so easy to make you can do it at home as a kid-friendly science project. In fact, milk was commonly used to make various plastic objects like buttons, beads and combs in the early 1900s. It readily takes surface dye, so it’s easy to mix into a wide variety of colors including pearlized and faux-tortoiseshell effects. After the advent of newer plastics, its use declined, but casein plastic could make a comeback. The vessels above were designed by Royal College of Art graduate Tessa Silva-Dawson for a project called “Protein.”

Molded Mycelium

Since pretty much nothing would ever biodegrade without the help of bacteria and fungi, it’s fitting to use the linked cells of mycelium as a replacement for materials that can’t be broken down naturally. Mycelium is the underground portion of fungi we see growing out of the soil, and it can be used to produce a surprisingly strong substrate that can be grown into molds of virtually any size and shape. The secret is in its tiny chains of tubular cells, binding together with natural materials like leaves and mulch to create dense mats.

A company called Evocative Design uses several species of fungi along with farming byproducts like seed hulls from rice and cotton gin waste to create a sort of styrofoam alternative that’s actually more UV-stable than foam and just as water-resistant. They break down within 180 days, whether in a landfill or somebody’s backyard.

Another biodegradable material called Mycoform is made from a composite of Ganoderma lucidum mushrooms, wood chips, oat bran, gypsum and other organic components. Also grown in molds, these networks of mycelia become strong enough to support significant weights, so they can be used to make furniture, insulation and interlocking walls for architecture. Some designers are even experimenting with ways to use them as a primary building material.

Considering that 18 billion pounds of plastic waste flows into the oceans every year from coastal regions and microplastics are actively endangering the entire food chain, refining biodegradable alternatives like these and producing them on a mass scale can’t happen soon enough.

Top image: Ooho edible water pouches made from agar