Robert Fielding’s Oz-some art cars once lit up desert highways; now they’re being painted, illuminated and photographed in their final resting places.

One does not simply drive across the Australian Outback (even in a Subaru) without being prepared for the worst. Those who took the oft-inhospitable, mostly desert region that makes up most of the Australian continent lightly have left cautionary reminders, in the form of dozens of rusting abandoned vehicles, scattered across the parched red wastelands.

Many of these junked cars, trucks, and even the odd ute (yes, we said “ute”) or two can be found in the Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara (APY for short): a 39,633.4 square mile Aboriginal local government area that occupies the remote north-west corner of South Australia state. A mere 2,276 people (as of 2016) reside in the APY lands; one of whom is artist, painter and photographer Robert Fielding (above).

Fielding is of mainly Aboriginal heritage and his home base is Mimili, a small community of under-300 situated in the rocky, drought-stricken Everard Ranges. It’s no surprise desperate travelers abandoned their vehicles in the scrubby desert just off the Stuart Highway (“The Track” through The Outback). No doubt their forlorn presence struck a chord in young Fielding, who was born in Lilla Creek just north of the APY lands.

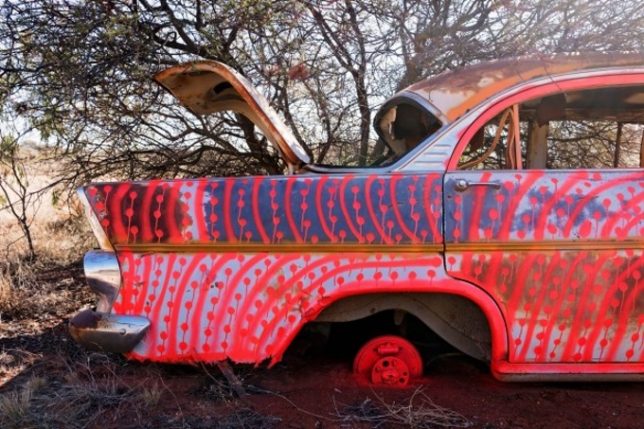

“I’m salvaging what belonged to the elders of our communities throughout the APY Lands and from Indulkana and Mimili, and bringing these cars to life,” explains Fielding. The artist’s use of these abandoned relics of modern life as media for expressing traditional indigenous art offers a novel method of interpreting the Aboriginal experience through the prism of recent history. In other (and much less) words, it’s cool!

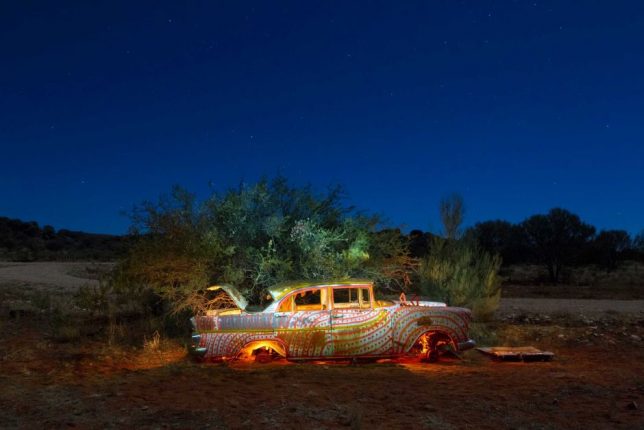

Fielding’s long-exposure night photographs are the result of a labor-intensive process involving the application of reflective paint and the strategic placement of natural light. “I’m lighting them up with tealight candles and giving it another feeling and another ghostly effect with what’s going on,” according to Fielding. “There’s a light within this vehicle that’s hidden in crevices throughout.” Unpredictable weather conditions and the chaotic flickering of the candles try Fielding’s patience and test his stamina as he waits to capture the perfect shot.

Fielding has no issues when it comes to redefining prehistoric art traditions for the modern age, and he’s eager to apply the latest digital technology to assist his photography. “The reason I like new media is the camera is a tool that indigenous people are very strong and proud to be in front and behind the lens,” he explains.

Fielding has stayed close to home and close to his subjects while working out of the Mimili Maku Arts center in the APY Lands. Recognition has come from afar, however, since he was awarded top prize in the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Awards twice in the past three years. He has also left the APY to host solo exhibitions of his work in Adelaide and Melbourne, while several of his photographs have been acquired by the National Gallery of Australia. It seems that even in The Outback, a short drive can take you a long way.