Google’s Street View has made it easier for us to find our destinations, but has it influenced us in other ways as well? When Google sent out a fleet of automobiles armed with GPS units, laser rangefinders, and multi-eyed cameras, their goal was to make it easier to navigate places around the world. But the cameras caught much more than street signs, storefronts and city scenes. They recorded a never-before-seen side of humanity, urbanity and photography itself.

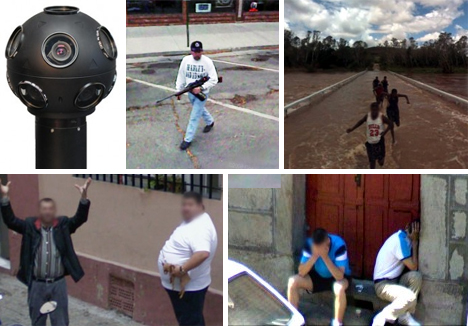

Though these images were all captured by Google’s Street View cameras, they were compiled by artist Jon Rafman. By combing through various blogs dedicated to Street View images, and by exploring the street view function on his own, Rafman was able to identify images that stood out from the rest. He collected those that interested him into an online portfolio of the amazing, the mundane, and the surprisingly intimate.

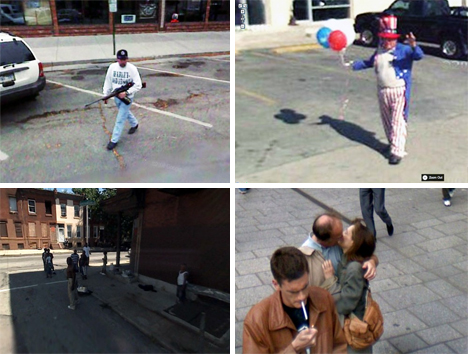

Rafman published a small book of his findings, and his essay about the project is touching. He describes how it was the unemotional, amateur aesthetic of the images that first attracted him to Street View photos. But as he dove in further, he began to see the unintentional documentary portrayed by these candid, neutral depictions of our world. The cameras make no judgments and display no prejudices. They simply capture the world, semi-autonomously, documenting a brief moment in time again and again and again.

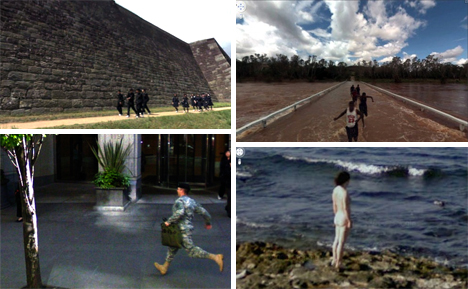

Since May of 2007, Google’s vehicles have been roaming the streets of the world. The nine-lens cameras atop the vehicles shoot photos every ten to twenty meters. Later, the images are stitched together to create 360-degree views of everywhere the vehicles have gone. The drivers of the vehicles don’t strive to catch interesting scenes; nor do they avoid unusual sights when they come across them. The project’s goal is simply to make public information available to the public.

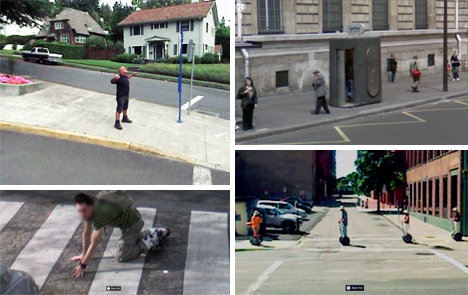

But inevitably, when the vehicles capture pictures of streets and neighborhoods, they see other things as well. They see the people occupying those streets. They see crimes or celebrations in progress, the aftermath of accidents, humorous situations, and couples passionately embracing. The people who are enraged at the presence of the cameras, the people who are clueless, and the people who play to the presence of their impromptu paparazzi. The presence of remarkable humans, the poignant lack of humans. These roving cameras are the voyeurs of the new millennium, yet they make no comment on any sight. The product of their worldly travels is a new class of photography: the utterly detached, emotionless, right-place-at-the-right-time scavenger hunt that is Google Street View.

Looking through pages and pages of photographs from Street View, Jon Rafman found a kind of rhythm in the images. Their slightly distorted proportions (thanks to the panoramic aspect), the faces and license plates blurred out (along with the occasional missing head or distorted body), and their ever-present navigational arrow and Google copyright all contribute to the unique style.

Rather than detracting from the experience, Rafman says that the frankness about how the images were made only enhances the experience. These images clearly are not meant to be art, yet we as humans feel the drive to assign an emotional value to them. Regardless of the method of recording, when we see another human being we have an emotional reaction to it. And that is the often-overlooked beauty of Google Street View images. They are a representation of what we have become. We live in a world that is automated and detached, we are so overloaded with information that we often overlook experiences, yet we still seek meaning in even the smallest things: a gesture, a look, a photograph of a stranger.

But this overarching meaning certainly isn’t Google’s intention. Their project consists of supplying neutral information about locations, not making any type of commentary on the human condition. However, Rafman points out that by removing these selected images from their original context and framing them in a more human-affected light, the artist returns the humanity to them. He bears witness to the frozen moments originally captured with no emotion and no affection, and he holds them out for everyone else to do the same. These tiny moments are a shared scrapbook, a global family photo album of unintentional tenderness.