Few places are as incongruously silent as abandoned racetracks, and the Sitges-Terramar Autodromo Nacional near Barcelona, Spain has slumbered in quiescence much longer than most. Built in 1922, Sitges-Terramar’s steeply banked concrete roadway has withstood almost a century of disuse surprisingly well while automobiles and auto racing have evolved exponentially around it.

The Real Roaring Twenties

(image via: WIEN)

(image via: WIEN)

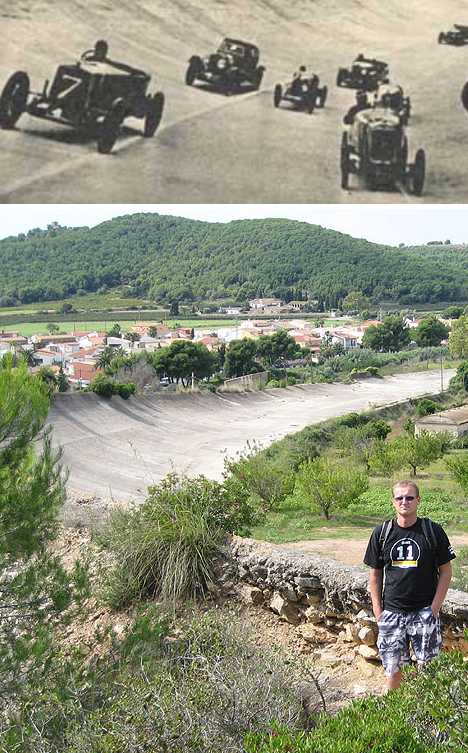

Consider a peaceful walk in the Catalonian hinterlands, warmed by golden sunlight and accompanied by delicate birdsong… but the quiet, deserted track at Sitges-Terramar wasn’t always so. For a brief, shining moment, this state-of-the-art auto racetrack was the site of pitched rolling battles between skinny-tired, brass-trimmed Grand Prix racers. Nearly a century has passed since Sitges-Terramar enjoyed its place in the sun yet the track and most of its outbuildings still stand, remarkably complete. How did this come to pass? Fasten your seatbelt, Sherman, we’re going for a ride…

(images via: LeBlogAuto and Peter Morley)

(images via: LeBlogAuto and Peter Morley)

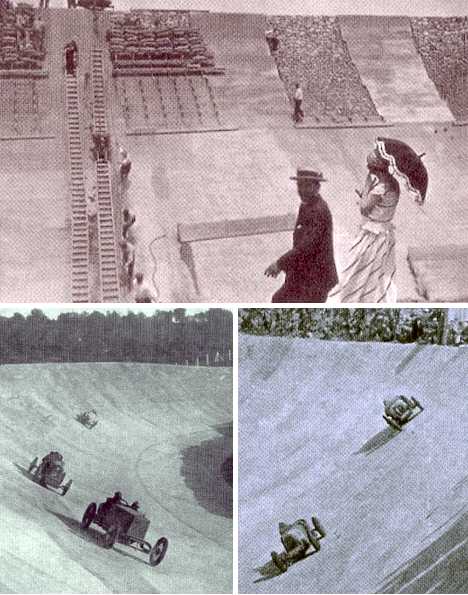

The term “Roaring Twenties” is mainly used to describe the era between World War I and the 1929 Wall Street market crash; a time when technology, stock prices and flappers’ skirts rose to giddy heights. It was also the age of the automobile, especially on modern banked racetracks designed to keep speeding cars firmly grounded as engines (and crowds) blared deafeningly.

(images via: LeBlogAuto and Peter Morley)

(images via: LeBlogAuto and Peter Morley)

The “father” of Sitges-Terramar was Frick Armangue, a local racing hero who, in 1922, founded Autodromo Nacional S.A with the intention of building the country’s finest car and cycle racetrack. Armangue hired Jaume Mestres to design the track and Josep Maria Martino to construct the facilities. Approximately 3.5 million kilograms (7.7 million pounds) of cement was ordered and slowly but surely, the Autòdrom Nacional Sitges Terramar took shape just outside the fishing village of Sitges, roughly 35 km (about 22 miles) from Barcelona.

(image via: Sitges4U)

(image via: Sitges4U)

“Slowly” is a misnomer – the track and facilities were completed in a mere 300 days though at the heavy price of 4 million pesetas. What racing fans got was a 2km (1.25 miles) long kidney-shaped course whose semicircular corners were steeply banked at up to 60 degrees. By comparison, the highest banking at any current NASCAR track is “only” 36 degrees, at Bristol Motor Speedway. In addition to the grandstand, viewers were able to perch on the outer (and upper) reaches of the track as well as the raised edges of the infield. All that was left was to wave the checkered flag and start the race… ANY race.

On the Beaten Track

(images via: Find-a-Grave, Motorsnaps and Peter Morley)

(images via: Find-a-Grave, Motorsnaps and Peter Morley)

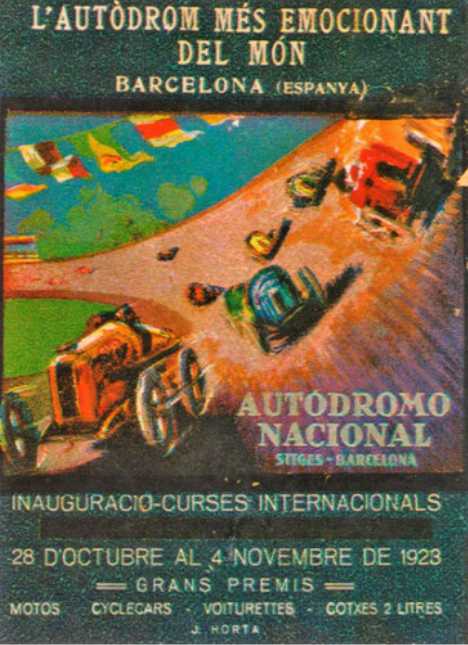

Fortuitously, 1923 was the year in which Spain returned to the world Grand Prix calendar for the first time since 1913. Races were held on July 25th at the Circuito Lasarte near San Sebastián and on October 28th at Sitges-Terramar. The latter event was promoted via beautiful posters and by all accounts was a great success even though only 7 cars participated, 5 of which completed all 200 laps.

(images via: Peter Morley and Icollector)

(images via: Peter Morley and Icollector)

The 1923 Gran Premio d’España was restricted to 2-litre GP cars which included those made by Alfa-Romeo, Aston-Martin, Elizalde, Miller and Sunbeam. The official winner was Frenchman Albert Divo driving a Sunbeam, finishing in 2 hours, 33 minutes and 50 seconds at an average speed of 155.89 kph (96.91 mph). Divo nosed out Count Louis Zborowski’s Miller 122 by a mere 56 seconds.

(images via: Formula 1 Database and Sportauto.ee)

(images via: Formula 1 Database and Sportauto.ee)

Unfortunately for Divo, the thrill of victory was all he was able to take away from Sitges-Terramar: no prize money was awarded to any of the contestants. It seems that Frick Armangue was a better driver than a financier – unpaid cost overruns compelled the track’s construction contractors to seize the Grand Prix’s gate receipts leaving organizers empty-handed (and doubtless red-faced). International auto racing authorities were peeved to say the least, and they expressed their displeasure by withholding their sanction on any future races at Sitges-Terramar. The next several decades saw only scattered racing events at the track

(image via: LeBlogAuto)

(image via: LeBlogAuto)

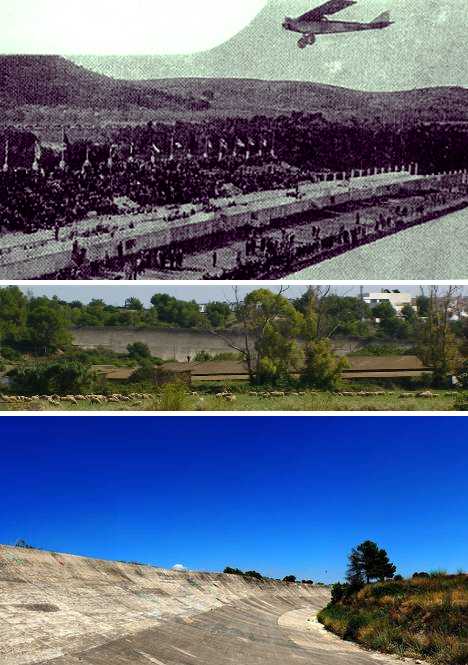

How’s that for “cheap seats”? One imagines drivers at a post-WWII Volta a Catalunya (“Tour of Catalonia”) event would be dodging rolling apples, wine bottles and the occasional wayward child along with their fellow racers. It’s interesting to note the rather large clump of weeds sprouting through the concrete in the photo above, taken at one of the last races run at Sitges-Terramar in the mid-1950s.

Silence of the Lamborghinis

(images via: Peter Morley, Sportauto.ee and Rub851/Panoramio)

(images via: Peter Morley, Sportauto.ee and Rub851/Panoramio)

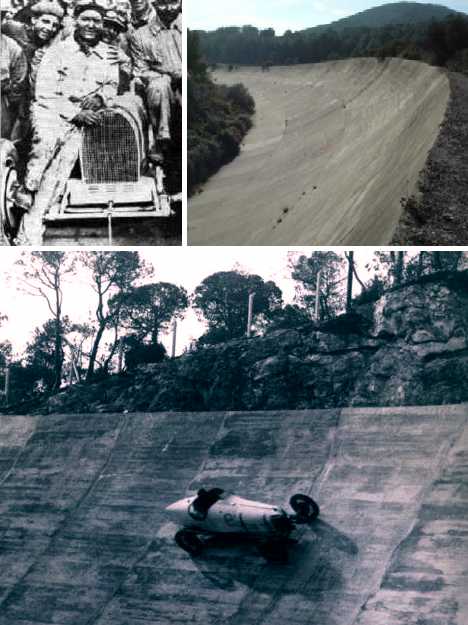

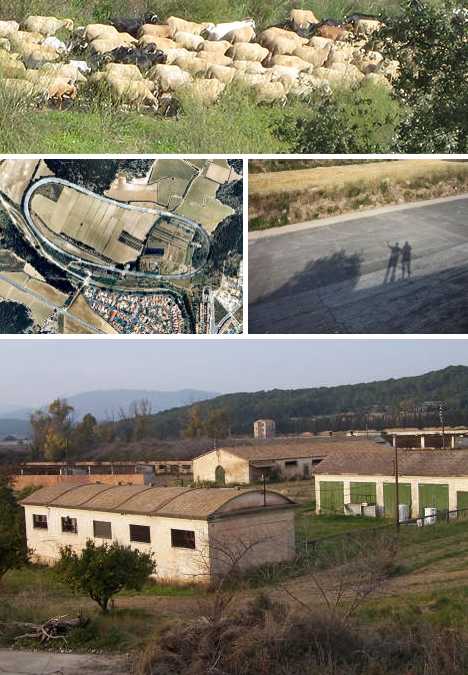

Fast forward fifty-odd years and very little has changed at Sitges-Terramar – clumps of weeds poke through the concrete in places but on the whole, the whole track could be made race-ready in surprisingly short notice. The airfield that used to take up a portion of the infield is gone for good, however.

(images via: Peter Morley)

(images via: Peter Morley)

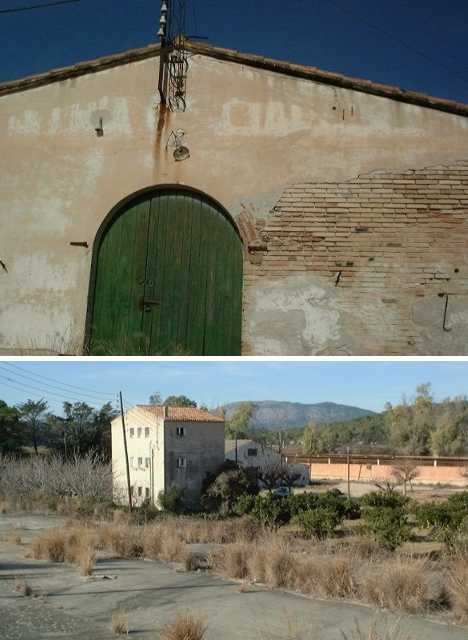

Perhaps we should give Frick Armangue a bit more credit. He may have been a lousy money manager but he had the foresight to specify only the best materials and delegate construction contracts to the best-qualified forms and engineers.

(images via: Peter Morley and CarType)

(images via: Peter Morley and CarType)

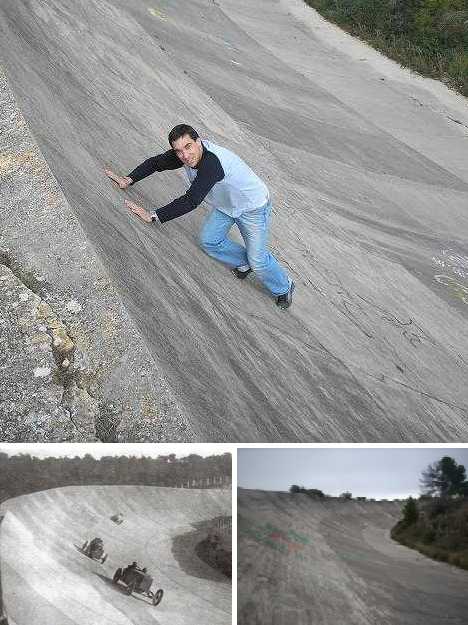

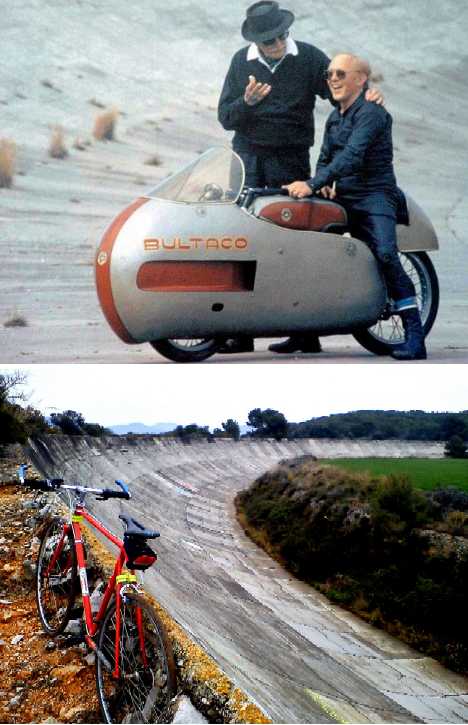

The proof is in the pudding: the Autodromo Nacional’s segmented concrete surface has barely aged, while the similarly constructed Brooklands racetrack became uncomfortably bumpy mere months following its completion. It’s even possible to see the imprints of tires long rotted into dust – some racers couldn’t wait for the concrete to fully dry!

(images via: Mercado Racing and Fastest Lap)

(images via: Mercado Racing and Fastest Lap)

Certainly weather must be considered as a contributing factor to the longevity of the Sitges-Terramar racecourse. Catalonia’s temperate clime and infrequent rainfall are much easier on poured concrete than Britain’s damp seasons and whip-sawing freeze-thaw cycles.

(images via: Sportauto.ee, CarType and G deCarli)

(images via: Sportauto.ee, CarType and G deCarli)

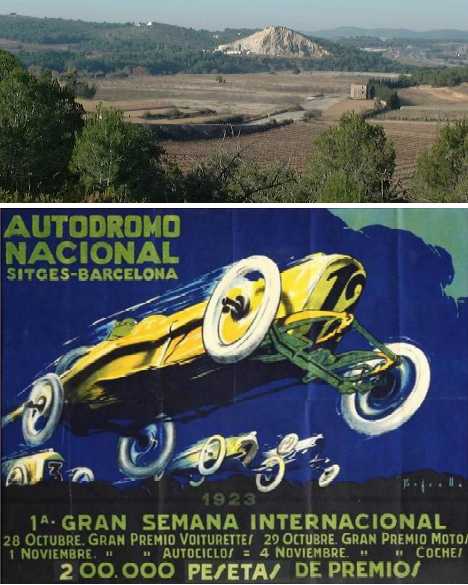

Sitges-Terramar’s relative isolation has also helped it stay in one piece, although its distance from Barcelona discouraged many race-goers in the early 1920s. The complex may be abandoned but it’s not neglected: a chicken farm exists in the former infield and takes up some of the old auto repair barns, while sheep graze in the relative peace and quiet of the countryside.

Drive to Revive?

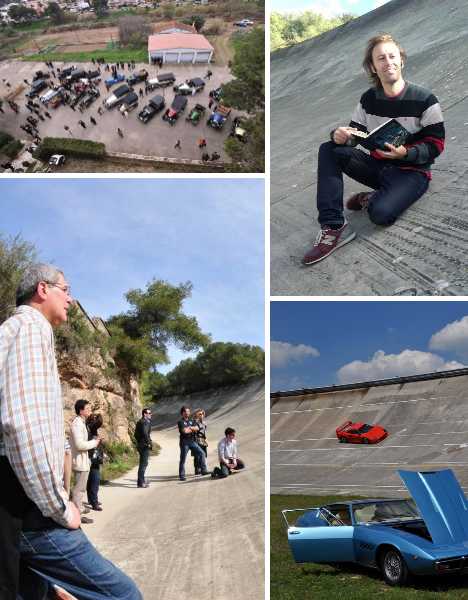

(images via: CarType, Colla Verglas, Sala de Prensa and Formfreu)

(images via: CarType, Colla Verglas, Sala de Prensa and Formfreu)

Old auto racetracks never die but they don’t exactly fade away either. At least, very few have the chance. Sprawling over hundreds of acres and easily overtaken by urban sprawl, almost all of the legendary racetracks of the past have passed into history. Not Sitges-Terramar, though, and there may be life in the old girl yet!

(images via: VespaBCN)

(images via: VespaBCN)

Ownership of Sitges-Terramar has changed hands many times since 1930 when Edgard de Morawitz took it off the original builders’ hands. The current owner, Marcel Ricart, is also the latest visionary to see the potential of a 90-year old racetrack that remains in good condition. Though the City of Sitges has officially bestowed landmark status on the site, the Ricart family is working with elected authorities in an effort to renovate and revitalize Sitges-Terramar by creating “L’Autodrom Resort“.

(images via: La Moto Classica and Ciclismo Ninja)

(images via: La Moto Classica and Ciclismo Ninja)

In the meantime, Sitges-Terramar’s aged yet resilient concrete hasn’t exactly been collecting dust. Vespa motorscooter clubs, classic car concours, vintage motorcycle runs, intrepid photographers and more have all taken advantage of the rusty circuit’s timeless atmosphere. Grand plans like resorts take time to implement; well-built racetracks like Sitges-Terramar eat time for breakfast.

(image via: Dogsville)

(image via: Dogsville)

Whatever the future may hold for the Autòdrom Nacional Sitges Terramar, there’s no doubt the past has an equal or stronger hold. Do the ghosts of long-lost racers deprived of their hard-won prize money softly rumble around the course late at night, riding high on the banked corners, eyes peeled for the checkered flag that never flies? If you go to Sitges-Terramar and dare to put your ear to the ancient concrete, you just might hear them.