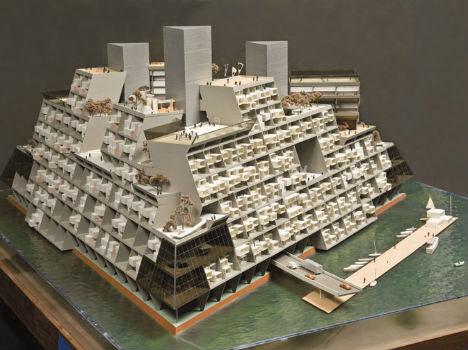

Triton City: Floating Concept by Buckminster Fuller

Autonomous, earthquake-proof floating cities could sustain themselves by desalinating and recirculating sea water, growing their own food and supporting their own economies in this vision from Buckminster Fuller. Each ‘Triton City’ unit could house 3,500 to 6,000 residents in terraced ‘garden apartments’, and join into larger units supporting a million people. Fuller was initially hired by a Japanese patron to plan the project, and later commissioned by the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development to determine the feasibility of U.S. use. The City of Baltimore was interested in anchoring one just offshore in Chesapeake Bay. But the plans faltered, and the model is now on display at the Lyndon Johnson Presidential Library in Texas.

Triton City was technologically possible in the 1960s, when the plans were produced, and is used as the basis for new plans by contemporary architects, though the minimum estimated cost of $500 million is a bit of a hurdle.

Museum of Tolerance by Frank Gehry, Jerusalem

Frank Gehry’s design for Jerusalem’s Museum of Tolerance was controversial from the start, and not just because so many people found it absolutely hideous. The Israeli counterpart to L.A.’s Simon Wiesenthal Center was slated to rise on a site that was found, during early construction in 2006, to be an ancient Muslim cemetery. Arab leaders and ultra-Orthodox Jews actually came together to stop the project due to their beliefs against disturbing graves, though their suit was thrown out after a three-year court battle. But in 2010, Gehry quit the project, and the budget and scale was cut in half. Work on the foundations has continued, but with the project losing local support, it’s unclear whether it will ever be completed. The new proposal, by a group of Israeli architects, is a little bit more – shall we say, subtle – than Gehry’s design.

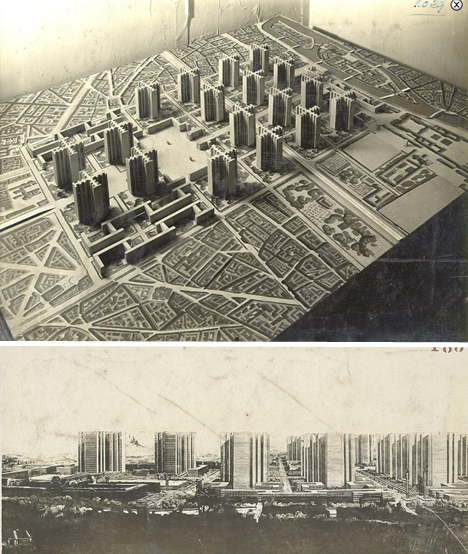

The Radiant City by Le Corbusier

Rigid order is the defining feature of Le Corbusier’s La Villa Radiusse (The Radiant City), a concept for compact urban landscapes envisioned in various forms for cities like Paris (Plan Voisin, 1925.) The grid of cross-shaped skyscrapers housing 2,700 residents each with interior streets connecting one building to the next aimed to eliminate the chaos and mess of urbanity. Corbusier called it ‘design on a human scale,’ yet the structures were massive concrete monstrosities set apart by wide-open plazas.

Le Corbusier was disgusted by the streets of big cities, writing in his description of Plan Voisin, “Rising straight up from [the street] are walls of houses, which when seen against the sky-line present a grotesquely jagged silhouette of gables, attics, and zinc chimneys. At the very bottom of this scenic railway lies the street, plunged in eternal twilight. The sky is a remote hope far, far above it. The street is no more than a trench, a deep cleft, a narrow passage. And although we have been accustomed to it for more than a thousand years, our hearts are always oppressed by the constriction of its enclosing walls. Nothing of all this exalts us with the joy that architecture provokes. There is neither the pride which results from order, nor the spirit of initiative which is engendered by wide spaces.”

This vision was carried out on a small scale at Cite Radieuse in Marseille, a Brutalist apartment complex built to house people left homeless by World War II, and its influence can still be seen all over the world in the work of other 20th century architects.

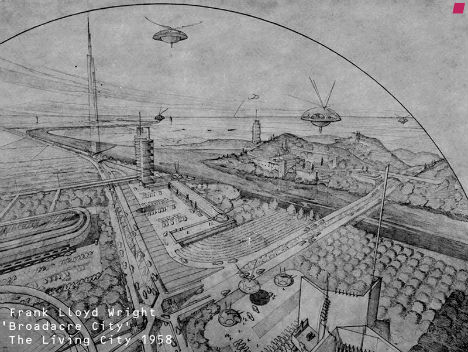

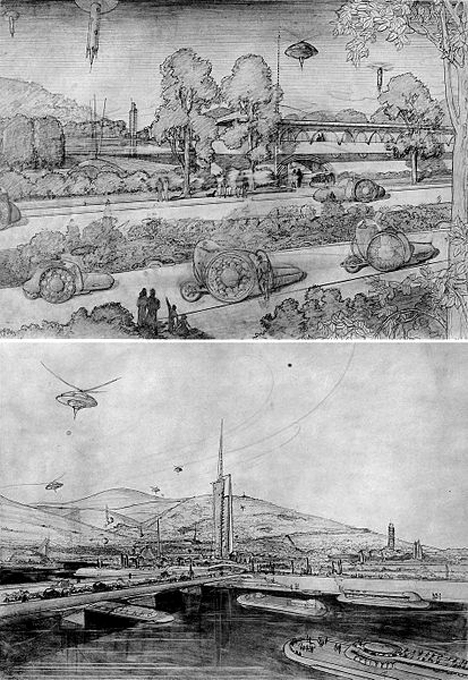

Frank Lloyd Wright’s Broadacre City

To Frank Lloyd Wright, Broadacre City was a utopia: a ‘fix’ for the modern city of the 1930s, which would be organized along the all-important highway. Wright’s vision of golden suburban sprawl included massive lots with their own helicopter landing strips, a study in wastefulness organized around nuclear families with money. Written on one panel of the Broadacre model displayed at the Rockefeller Center in 1935 was ‘No Slum. No Scum. No Traffic Problems. No glaring cement roads or walks.’

Broadacre City was a direct response to The Radiant City, as fundamentally different from its compact, minimalist urban design as can be (Le Corbusier has been described as Wright’s ‘nemesis.’) It was widely dismissed as elitist and unrealistic by urban planners of the time, not only for its glaring exclusion of singles and the poor, but for the fact that even the city’s largest ‘villages’ could only house 10,000 individuals.

Of course, Wright’s vision could never replace actual cities, no matter how much he wished for an end to urbanity, but it did predict modern suburbs with eerie accuracy.