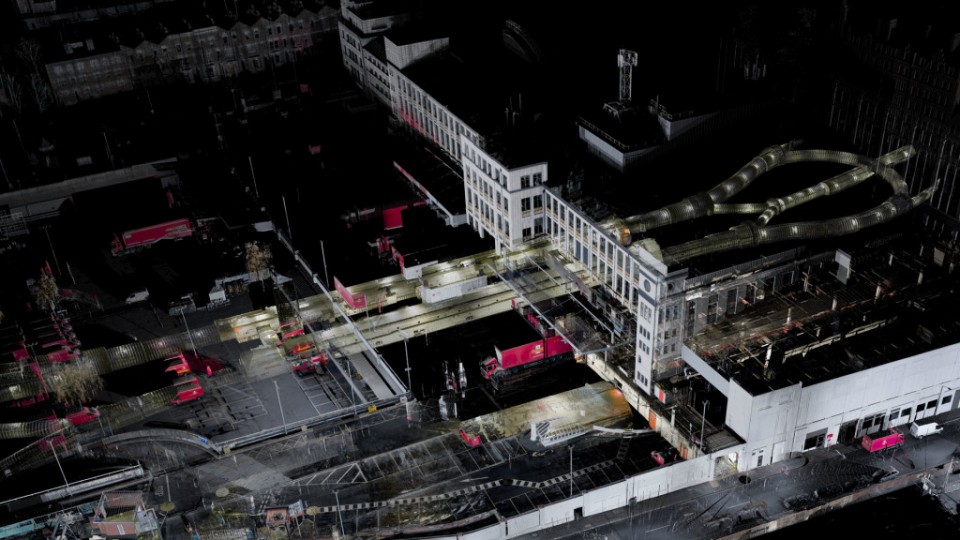

Produced from over 200 laser scans, this remarkable 3D representation covers surface features as well as subterranean spaces of it’s London subject, captured and stored as a series of over 10 billion points. This data-rich compositing process has been called everything from spatial scanning to volumetric photography, but the goal is simple: capturing all dimensions of the subject matter in digital space. And as the cost of the requisite technologies continues to drop, it may not be long before lidar (laser + radar) scanners become commercial household products or even smartphone features.

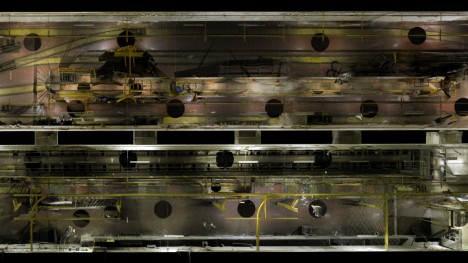

The duo behind ScanLabs has done remarkable projects around the world, both artistic and documentary in nature, but their work with Mail Rail illustrates the near limitless potential of the technologies they employ. Using scanner that sent out millions of laser light bursts per second, they have generated a ground-piercing, interactive rendering that is ahead of its time. Static views and videos do not do their captures justice, which may someday be best experience via virtual reality or in some other format yet unimagined.

Matthew Shaw and William Trossell were commissioned to help document The London Post Office Railway by the British Postal Museum & Archive before a section is converted into an underground ride. The nearly 100-year-old and 23-mile-long LPOR, or ‘Mail Rail’ for short, transported millions of pieces of daily mail beneath the city at its peak. Before a massive revamp changes this subterranean landscape forever, stakeholders wanted a method for preserving all elements of the existing spaces.

As Geoff Manaugh summarizes this novel approach to spatialization, “Their 3D point clouds afford a whole new form of representation, a kind of volumetric photography that cuts through streets and walls to reveal the full spatial nature of the places on display.”

ScanLab has engaged in many other projects as well, including augmented archeology at concentration camps and digital preservation of D-Day landing sites. Some, however, are simply experimental, designed to push the limits and explore ways to hack the technologies they use. The company has done everything from generating surrealistic renderings of forests to scanning clouds and mist simply to see what will come out the other side of the process. They have even snuck into famous works of architecture and surreptitiously scanned buildings, then recreating them in perfect detail with 3D printers or CNC routers. Regardless of the short-term applications, the key is the long-term data storage – the information being preserved today may be redeployed in the future in ways not yet envisioned.