Sure, Brutalist architecture is divisive, but does that mean we should be wiping it all off the face of the planet? It’s true that these structures are rarely beloved by the residents of their locales; they’re often derided as ‘monstrosities’ with their blocky proportions and large swaths of concrete surfaces. That makes them a major target of trigger-happy developers eager to treat architecture that’s just a few decades old like it’s disposable, making way for new models that will likely be torn down in even less time.

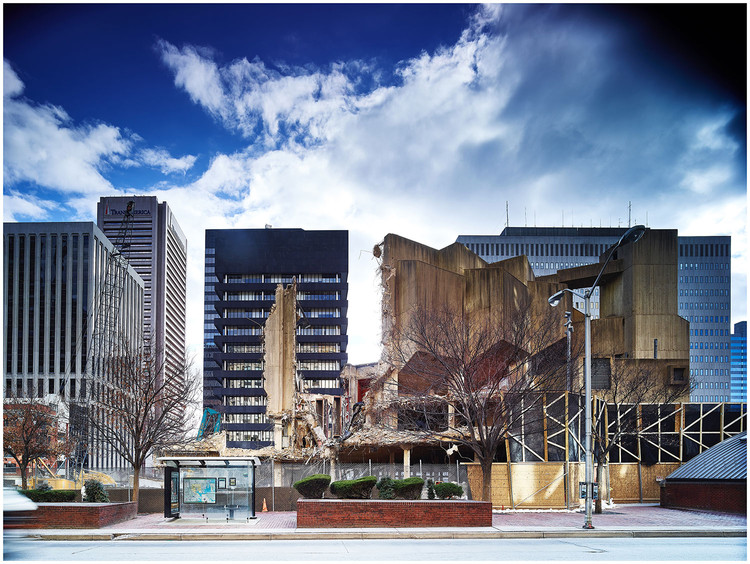

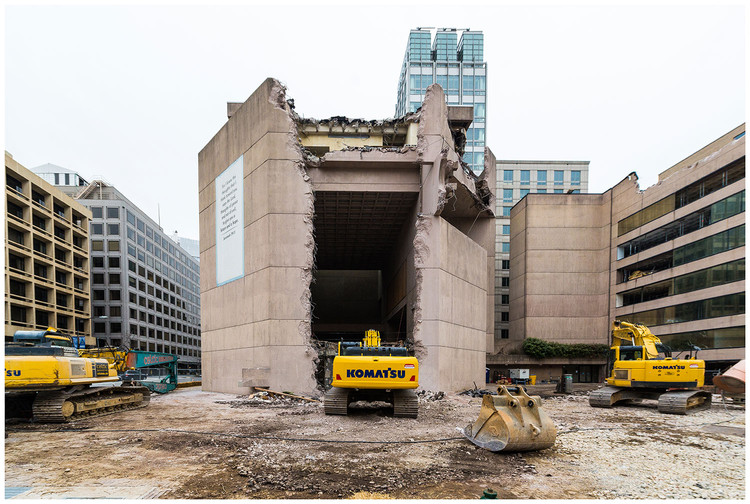

We’re all familiar with planned obsolescence by now, and it’s not surprising to see a lot of the cheaper, flimsier structures of the recent past fall to the wrecking ball – but Brutalist buildings, by their very nature, could stand for centuries if well maintained. Alas, many of them are already gone, and a new series of photographs entitled ‘Brutal Destruction’ captures them in mid-demolition.

Architect Chris Grimley of multidisciplinary design firm Over,Under curated the exhibition, opening this week at Boston’s Pinkcomma gallery. Each building is captured in a raw state of traumatic injury, halfway between existence and nonexistence, and looking at them, you get the sense that people are either cheering for their destruction or mourning their loss, with few feelings in the midrange.

Grimley himself is certainly among the latter. Along with his colleagues at Over,Under, the architect has helmed a number of Brutalism-centric projects, including the book Heroic: Concrete Architecture and the New Boston and a map of Brutalist Boston produced in collaboration with Blue Crow Media. Judging by the rate at which these structures are disappearing, that map may already be out of date.

Grimley notes that, even in our contempt for ‘ugly’ Brutalist buildings, we’re being a tad hasty. After all, previous generations tore down Victorian architecture because it was ‘out of date,’ and the window by which something becomes outmoded grows shorter every year.

“We get caught up in notions of what is considered beautiful,” he says. “By the time things are allowed to be considered beautiful again, it’s often too late.”