Plenty of architects can say they began from nothing, but few mean it quite so literally as Arata Isozaki. He was fourteen years old in 1945, when his hometown of Oita, located halfway between Nagasaki and Hiroshima, was destroyed by the United States’ atomic bombs. Looking around him in the aftermath, he says, he began to wonder what it would take to rebuild. “So, my first experience of architecture was the void of architecture.”

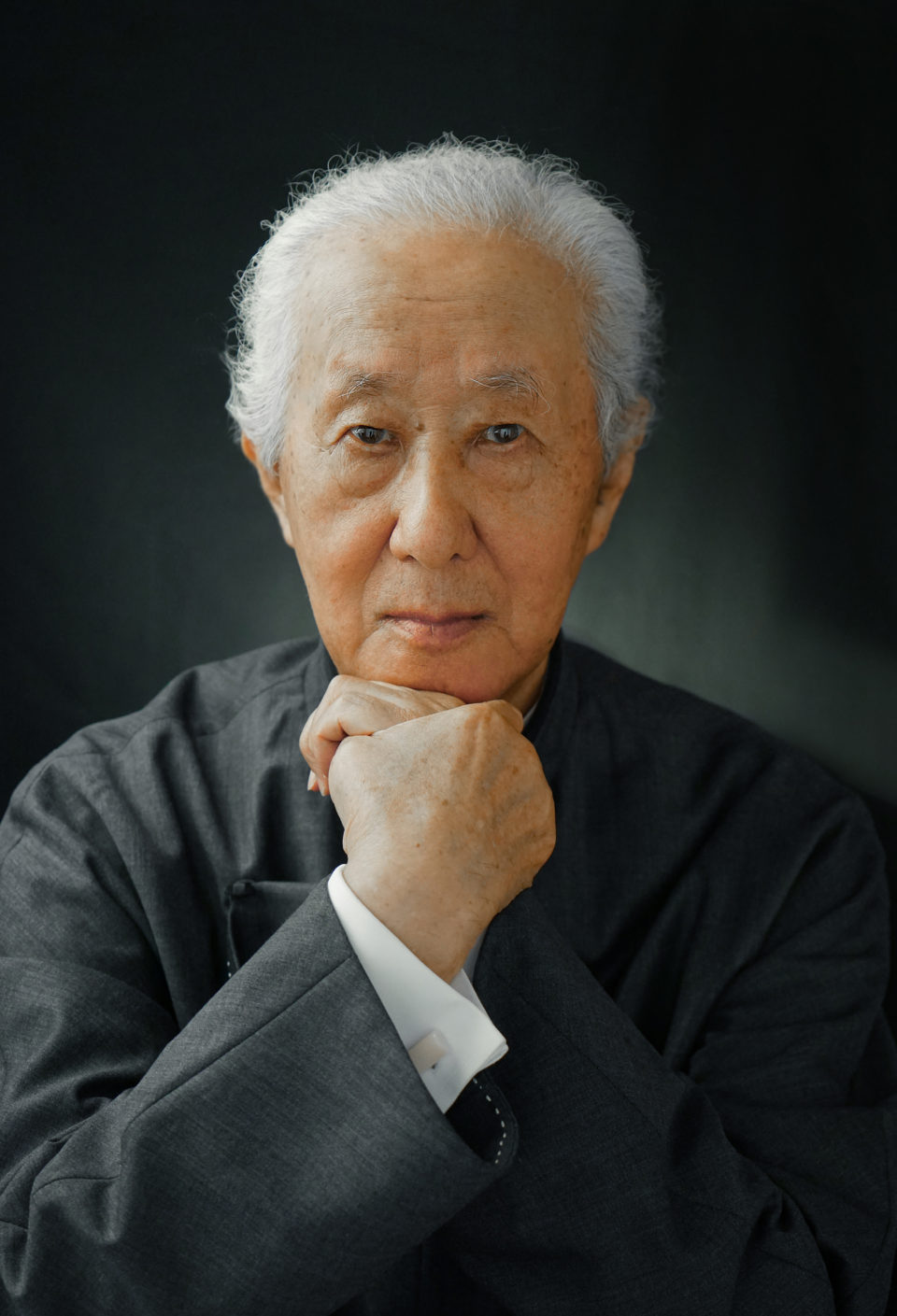

Recipient of the 2019 Pritzker Prize, architecture’s highest honor, Isozaki is getting more of the international attention he deserves after a decades-long career spanning continents and helping cities around the world grow from the ground up. Some observers might find his work a bit difficult to pin down; other than a repeated use of simple geometric shapes like cubes and pyramids, there are few connecting threads from one project to the next. Isozaki has defied conventions, refusing to cooperate with external demands that he define for himself a particular style, remaining open to flexibility and adaptability as he addresses the needs of each individual project.

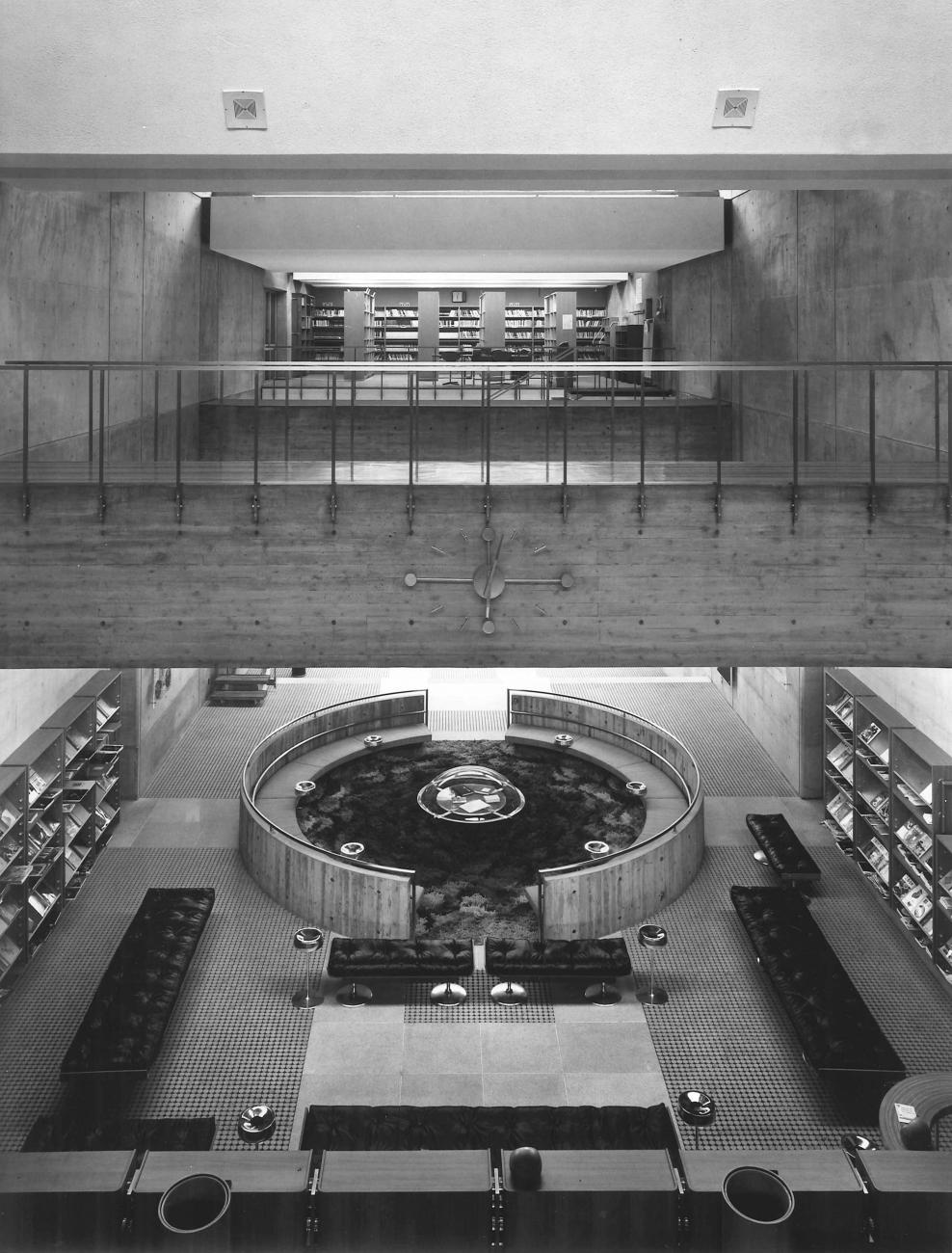

A 1954 graduate of the University of Tokyo, Isozaki first worked under the tutelage of future 1987 Pritzker Prize laureate Kenzo Tange, another of eight total Japanese architects to win the prestigious prize, but he quickly made a name for himself on his own merit. His first notable project was the Oita Prefectural Library (1966), which was repurposed as an art gallery in 1996 and is described by the Pritzker Prize jury as “a masterpiece of Japanese Brutalism.”

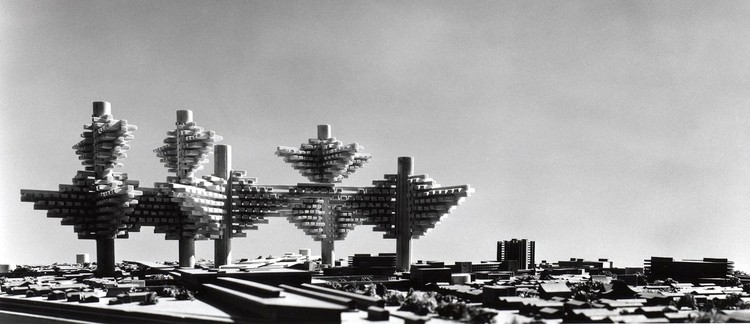

Other early works in Japan, including the Museum of Modern Art Gunma (1964) and the Kitakyushu Municipal Museum of Art, Fukuoka (1974) share this structure’s avant garde boldness. During this time, Isozaki also created futuristic renderings like City in the Air (1962), imagining a fresh veneer of urban life suspended above the existing fabric of Tokyo in response to rapid urbanization.

Isozaki’s first overseas commission was the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles (1986), representing one of the first major buildings in the United States to be designed by a Japanese architect. This swiftly led to more commissions, including large-scale projects that drew upon Isozaki’s initial fascination with building cities from scratch.

“If you look at the construction booms that I have experienced, they all started with my first job overseas, which was in Los Angeles — the Museum of Contemporary Art there,” Isozaki tells the Japan Times. “That was part of a very large-scale development. It was the same kind of project as the Mori Building’s Roppongi Hills in Tokyo, where they started with a large-scale development and then added in a hall or a museum to attract the people. MoCA was also the first museum focused on contemporary art in the world.”

“So, in America, in the 1970s and ’80s many large-scale developments were being made, and in Japan, too, at the end of the construction boom that continued through the 1980s, there were lots of ideas for similarly large-scale developments. Then the economic bubble in Japan burst, and all those ideas were scrapped. Now, I think the situation you see in Tokyo is that the ideas born in the bubble period are finally being realized.”

As he accumulated over 100 built projects around the world, Isozaki displayed his chameleon-like sense of adaptability, all tied together by his favored blend of geometric shapes and organic curves. His preference for dramatic modernist silhouettes gradually fell away as he approached each individual project with an eye for its context, and his sense of humor occasionally made way for unexpected solutions, like the question mark-shaped Fujimi Country Club (1973), which was reportedly a sign of his bemusement with Japan’s golf obsession.

Domus: La Casa del Hombre (1995), a science museum in Caruña, Spain, rises like a ship against the rocky cliffs; the 100-meter-tall Art Tower Mito (1990) in Japan takes a stack of glittering metallic tetrahedrons high into the sky; Ceramic Park Mino (2002) recalls the sensibilities of MOMA Gunma.

Over the years, Isozaki’s work began to display a certain softness. The Qatar National Convention Center (2011) is characterized by stretching branches supporting a cantilevered roof and penetrating the interior of the building. Allianz Tower, Milan (2015), completed in collaboration with architect Andrea Maffei, looks like an ordinary skyscraper from afar, revealing its gently billowing facade when you stand at its base. Others in this vein include the Palau Sant Jordi, Spain (1992), Nara Centennial Hall (1999), Shanghai Symphony Hall (2014) and his inflatable 2013 collaboration with artist Anish Kapoor, the Ark Nova.

“Isozaki demonstrated a worldwide vision that was ahead of his time and facilitated a dialogue between East and West,” write the Pritzker Prize jurors.

“Isozaki’s oeuvre has been described as heterogeneous and encompasses descriptions from vernacular to high tech. What is patently clear is that he has not been following trends but forging his own path… Clearly, he is one of the most influential figures in contemporary world architecture on a constant search, not afraid to change and try new ideas. His architecture rests on profound understanding, not only of architecture but also of philosophy, history, theory and culture.”