Years ago in McAllen, Texas, an old abandoned 124,500-square-foot Walmart superstore was renovated and put to new use as the largest single-floor public library in the United States. Across America, many malls have emptied out and thousands of abandoned big box stores sit empty, including hundreds of former Walmarts. Some, though, are getting creative new leases on life, becoming community markets, indoor tracks, gaming spaces, museums and more.

In McAllen, aisles that used to divide shoppers have been adapted or replaced to serve the community. The old Walmart is packed with computer labs, public meeting spaces, a cafe, an art gallery, a used bookstore and more. In other small towns and suburbs around the United States, the generic promise of all-in-one convenience big box stores once offered is being realized in new and site-specific ways.

Designers at the research and development lab of KTGY Architecture + Planning in Los Angeles have particularly inspiring aspirations for old shopping centers: plug-and-play modular prefabs that subdivide big empty boxes into transitional housing for the homeless. This is not the first time architects and designers have attempted creative solutions to this pervasive problem, but it’s notably ambitious.

The firm’s Re-Habit project involves housing as well as support spaces and services fit into unused spaces in big boxes or individual shopping outlet stores like Sears and JCPenney. Self-supporting communal residences, where occupants rotate chores like working in the kitchen or keeping the dining hall clean, are coupled with facilities to providing training and potentially even employment.

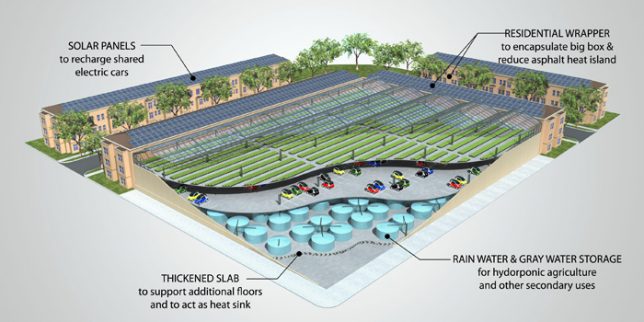

Where some might see empty space, others see opportunity. The large, flat roofs of big box stores, for example, are ideal for rooftop gardening, open-air recreation and solar panels — these kinds of uses would pair well with a project like Re-Habit. Many big boxes have outdoor plaza areas (not to mention giant parking lots) that could accommodate small pop-up shops and food carts, too.

Adaptive reuse in the realm of big retail is forward-thinking but also proven concept. Big boxes have been turned into commercial gyms, corporate offices, schools, churches and (yes, this is true) even a SPAM Museum. Whatever the project, it takes vision and resources to turn such dauntingly huge structures around as well as an understanding of the potential pitfalls and unique opportunities of this peculiar building typology.

Such large-scale conversions tend to work best when they take advantage of big box assets and work within their limitations. Generally, big box stores reside in huge buildings that are located in prime spots, often along highways, which makes them accessible but can also make them hard to fill up. They generally have a lot in common, like orientations that lend themselves to being sectioned into bays and limited natural light, features that can work well for things like libraries. Often, though, the best option is simply whatever best fits community needs, which is often a mixed-use program that can more effectively fill out a bigger interior.

Big retailers may be more prevalent in suburbs, but there are some prime urban examples as well. A series of converted Sears plants in major US cities offer a range of realized visions for what big old commercial buildings can become. In Minneapolis, for instance, a massive mail-order Sears plant and retail store was abandoned by its makers for years before being turned into the Midtown Exchange, a busy structure full of restaurants, stores, offices, condos and apartments. It took a lot of players to make this work, including invested city officials and both public and private funding from various sources.

Often, these conversions speak to the character of the cities in which they are located. In Seattle, a place known for its coffee, the city’s old Sears plant now houses the Starbucks headquarters. In Los Angeles, land of Hollywood, a deserted Sears was used for film shoots during its derelict years but is on its way to becoming a residential and commercial hub. Boston and Memphis have converted Sears projects, too — uses are mixed in both cases.

While the individual projects vary, each city has something in common having turned a similarly monumental structure into something new. These various projects fill in gaps and address needs that are fundamentally local. Together, they represent a series of blueprints that other cities can look to, whether they have Sears plants themselves or are simply looking for ways to deal with big old commercial spaces.

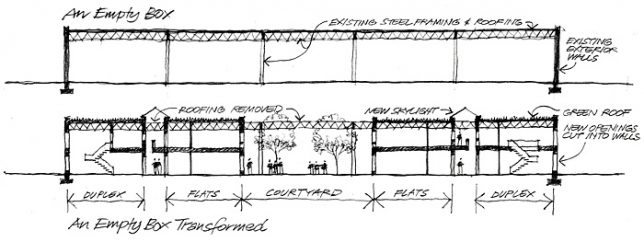

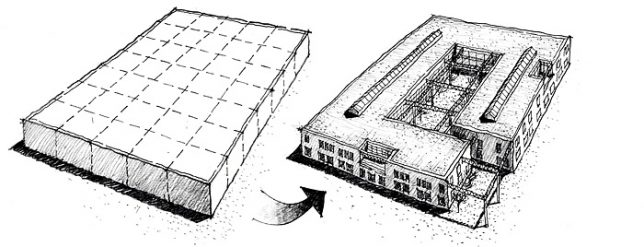

Existing examples can provide paths forward, but other architects have grander visions, too, some of which have yet to be tried. Designers could, for instance, build around big boxes on all sides, then turn the central old structures into community hubs or parking lots or productive green spaces. Another option is to tear down sections of roofs and facades, dividing big boxes up into smaller and more manageable units while leaving structural supports intact.

There is no one-size-fits-all solution for disused spaces, but cities, towns and sururbs looking for inspiration have both real-world examples and conceptual designs to draw on. In some sense, the core recipe never changes — for any big transformation project, municipal officials, citizens, developers and designers will always have to come together to find best-fit solutions on a case-by-case basis.