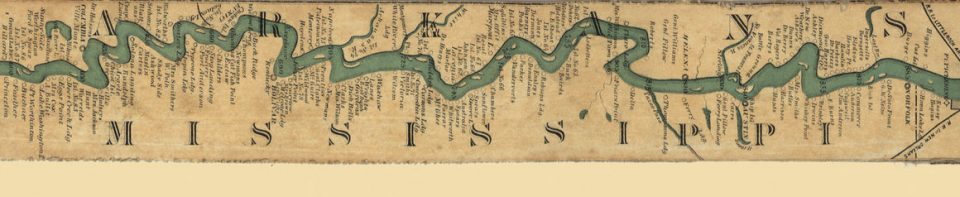

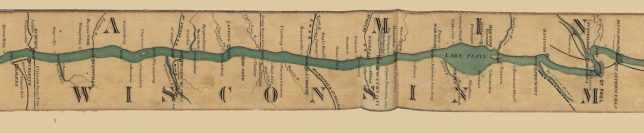

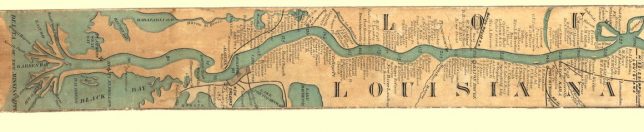

Designed for 19th-century travelers trekking up and down the mighty Mississippi on riverboats, these scrolled parchments unspooled to reveal major cities and points of interest worthy of note along the way. The Ribbon Map of the Father of Waters in particular had an impressive reach, spanning from Minnesota down to the Gulf of Mexico, just three inches wide but eleven feet long.

Unlike “network maps,” designed to allow users to seek out different points of interest and map out their own route, these “itinerary maps” documented a single path, like a long guide to a single trail versus an atlas.

“Strip maps arose from oral or written itineraries,” writes Cara Giaimo, “and were used by ancient Romans who wanted to plan trips to nearby towns, and medieval Europeans who hoped to make pilgrimages from London to Jerusalem. Reading one is like getting directions from a friend: left at this landmark, right at that fork.”

In the 1860s, a pair of St. Louis-based entrepreneurs made their first “ribbon map,” and patented an associated sheet-connecting technique and scrolling apparatus. If it had sold as well as they hoped (to passengers, not the captains who knew routes like the backs of their hands), they had plans to unfurl other linear maps for places like Broadway in New York City or rail lines between major cities.

And while some were sold, they never took off as intended, and, of course, have since been replaced by higher-tech solutions.