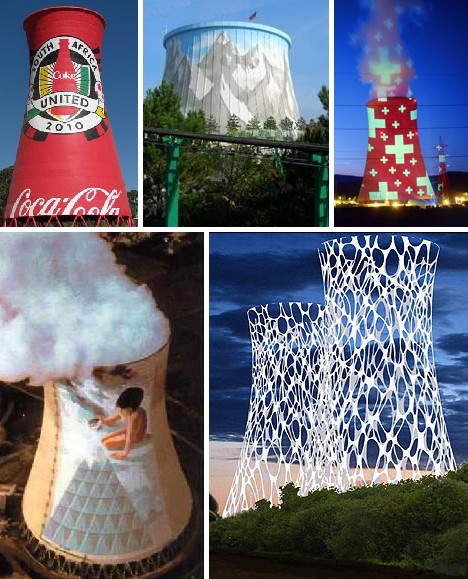

Cooling towers have come to symbolize power plants – nuclear or not – around the world. Standing hundreds of feet tall with a distinctive hourglass profile, some of these “towers of power” show an unexpected side: they’ve become colossal curvaceous canvases upon which an astonishing variety of art has been displayed.

New Clear Days

(images via: Dvice, Cartoonstock and World’s Largest)

(images via: Dvice, Cartoonstock and World’s Largest)

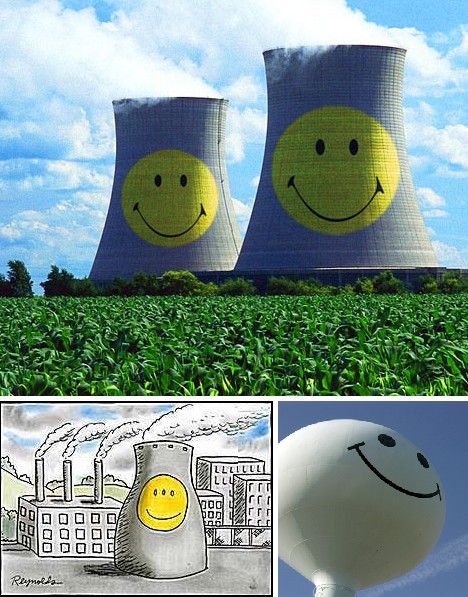

Pro-nuke overkill or an obvious photoshop: how to explain these outrageously over-the-top smiley face cooling towers? Most uses of this image have been used in a sarcastic, almost sardonic fashion by anti-nuclear bloggers or to illustrate left-leaning articles on the nuclear power industry. Is putting a Happy Face on the most visible part of a nuclear power plant really so wrong? Is it that much different than displaying the same classic icon on water towers, as has been done dozens of times? You be the judge… and have a nice day!

Hiding In Plain Sight

(image via: Art Of Deception)

(image via: Art Of Deception)

Cooling towers predate the nuclear age; a fact that may surprise many. During World War II, the British government sought to camouflage cooling towers (and more importantly, the power plants next to them) from Luftwaffe bombers. Painters were hired to try and blend the huge, obtrusive towers into the landscape.

(image via: Art Of Deception)

(image via: Art Of Deception)

One of the best of these artists was Colin Moss (1914-2005), an art teacher from Ipswich who studied at the Royal College of Art in London. Moss’s murals survive to this day because he often painted them from his point of view – paintings of paintings of cooling towers, as it were.

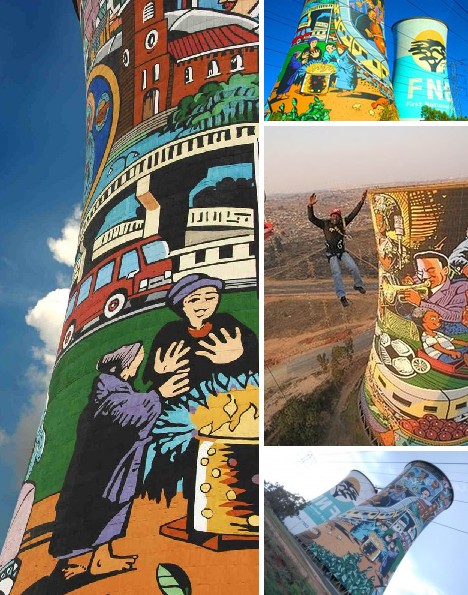

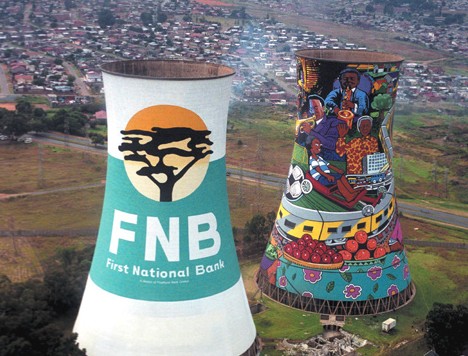

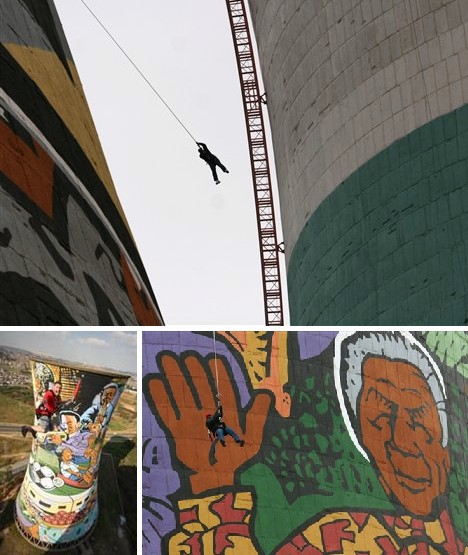

Soweto’s World ‘Cups’

(images via: Photo.net, Adventure Escapades, TravBuddy and My Digital Life)

(images via: Photo.net, Adventure Escapades, TravBuddy and My Digital Life)

This dynamic duo was part of the infrastructure cleanup and buildup leading up to the 2010 FIFA World Cup which took place this summer in South Africa. While one cooling tower is painted in the colors and logo of the sponsor, FNB (First National Bank), the other is a vibrant celebration of folk art that displays the culture and traditions of Soweto.

(images via: Suite101, Sulekha.com and WorldNews)

(images via: Suite101, Sulekha.com and WorldNews)

The coal-fired Orlando Power Station was the most technologically advanced in Africa when it was built but the station is now closed. Nice to see the old cooling towers being put to good use – besides the beautification, tourists can pay to ride a power swing between the two towers and even jump inside one from the 300-ft top rim!

Towers In Bloem

(images via: Shine2010/Photostream, Shine2010/Community and Just_Ice)

(images via: Shine2010/Photostream, Shine2010/Community and Just_Ice)

Emboldened by the positive press sparked by the Orlando Cooling Towers’ extreme makeover, other South African cities jumped on the bandwagon. One of the most notable was the city of Bloemfontein, who commissioned ad agency Draftfcb Johannesburg to freshen up four 200-ft tall cooling towers.

(image via: Shine2010/Community)

(image via: Shine2010/Community)

As with the Soweto project, FNB is deeply involved: two towers are painted in the company’s 2010 FIFA World Cup logo & colors. The other pair of towers displays artwork by local crafts-people that celebrates the heritage of South Africa’s “City of Roses”.

Coca-Cola Gets Cool

(images via: BlaBla Blog and Flat Michael)

(images via: BlaBla Blog and Flat Michael)

Another Soweto cooling tower, a single one this time, was painted in the colors and corporate logo of Coca-Cola. Though the image may be interpreted by some to show the enormous gap between South Africa’s poor and the exceptional wealth of multinational corporations like Coca-Cola, the hut in the foreground is actually a temporary structure set up and used by vendors who provide services to workers building the local soccer stadium.

(image via: Gregsaintclair)

(image via: Gregsaintclair)

From a distance, on the other hand, the Coke Tower looms large in splendid solitude without even its former power plant still standing to give it some scale and context. Things go better with Coke? Not always, it seems.

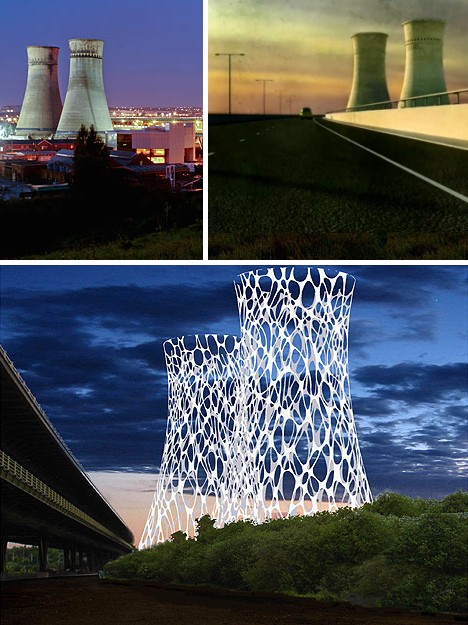

Tinsley: Yorkshire Teardown

(image via: BBC)

(image via: BBC)

“The Stonehenge of the Carbon Age”… this grand epithet was bestowed upon the twin cooling towers at Blackburn Meadows, Tinsley, Sheffield by renowned British sculptor Antony Gormley. Such status didn’t prevent the towers from undergoing explosive demolition in August of 2008, unfortunately, despite a noisy campaign by local government, the community and stakeholders to preserve them in some way, shape or form.

(images via: Channel4, BBC and Behind The Water Tower)

(images via: Channel4, BBC and Behind The Water Tower)

A competition to replace, re-work or upcycle the towers was won by landscape architect firm Insite Environments, whose striking lattice steel homage shown above now has a better chance of seeing the light of day now that the towers have been demolished.

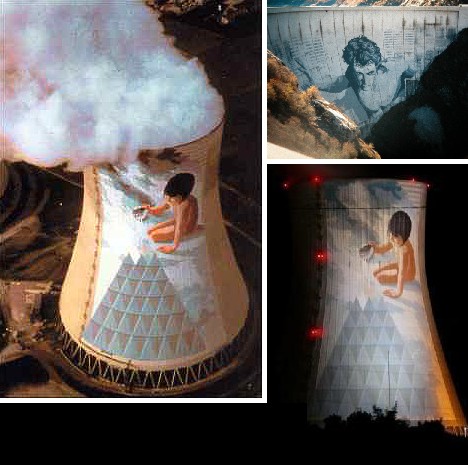

Cruas Nuclear Power Station

(images via: Gefield and Visuals Unlimited)

(images via: Gefield and Visuals Unlimited)

The Cruas Nuclear Power Station on the Rhone river was competed in 1985 and today provides France with nearly 5% of its electric energy annually. Four massive cooling towers serve the quartet of onsite nuclear reactors whose cores are kept comfortably chill by river water drawn from the fast-flowing Rhone.

(images via: Over The Net and Deputy Dog)

(images via: Over The Net and Deputy Dog)

In 1991 the owners of the power plant decided to improve the public perception of the Cruas station by ordering an ecologically-themed mural for one of the cooling towers. The commission went to Jean-Marie Pierret, whose previous work includes the enormous painting of Hercules on the face of the Tignes dam. Pierret enlisted 9 mountaineers who expended 8,000 working hours and 4,000 liters of paint before the mural – titled “Aquarius” – was finished in 2005.

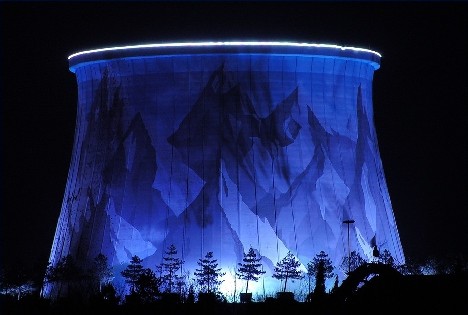

Light Monuments of Switzerland

(image via: Kernenergie)

(image via: Kernenergie)

The Swiss may not have a navy but they’ve got nuclear power plants – including this one: Kernkraftwerk Gösgen. The plant was one of a number of industrial, architectural and otherwise notable subjects in a wide-ranging Light Art exhibition conceived and organized by Gerry Hofstetter.

(images via: KKG)

(images via: KKG)

The advantage of Hofstetter’s methodology lies in its transience: transformed by night, the towers revert to their normal appearance by the next morning. Additionally, Hofstetter can change the tone, topic and type of design at his leisure, without needing to physically alter the surface of the towers or for that matter, the attached power plant and even the steam rising into the night sky.

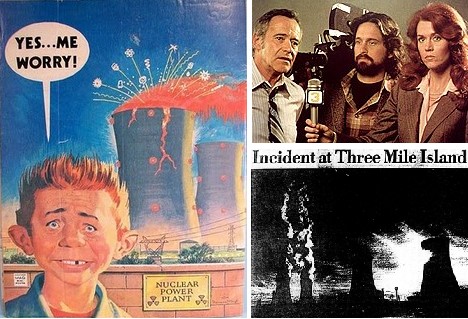

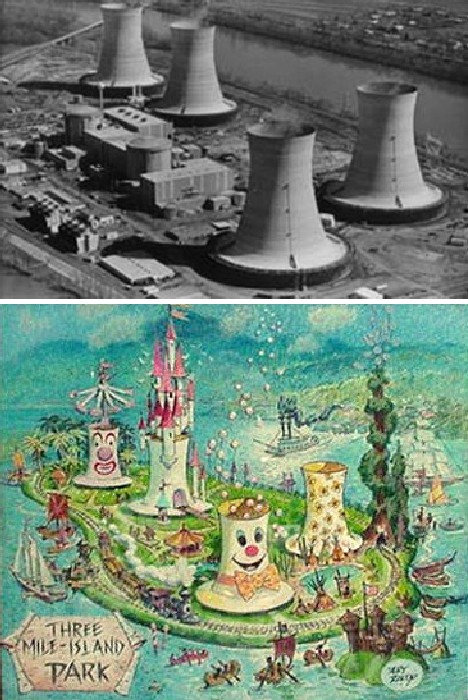

Six Flags Over Three Mile Island?

(images via: Switched and LA Filmcutter)

(images via: Switched and LA Filmcutter)

The widely reported and oft-satirized partial meltdown at the Three Mile Island nuclear power plant near Harrisburg, Pennsylvania caused many to re-evaluate their image of nuclear power. Indeed, the March 1979 accident – plus fallout from the release of the film The China Syndrome 12 days BEFORE the accident at TMI – helped drive the nuclear industry’s PR to its knees. The good old days of “Our Friend the Atom” were gone for good.

(image via: JustinSpace)

(image via: JustinSpace)

Protests and demands that Three Mile Island be shut down were met with varying responses, including Art Riley’s fanciful re-imagining of the plant as a Disney-style theme park. We’re not sure whose image suffers worse, power plants or clowns.

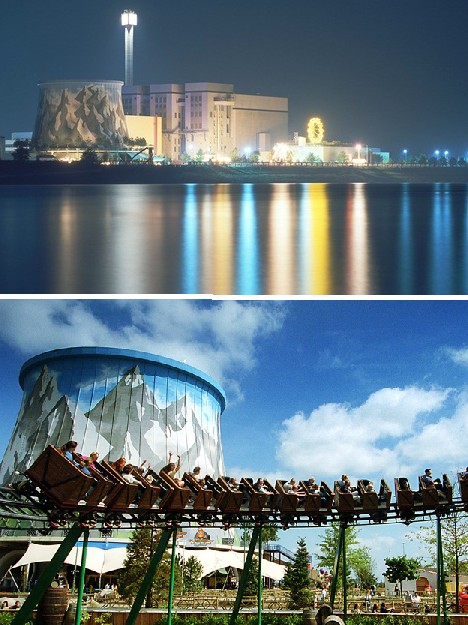

Post-Nuclear Wunderland

(images via: JustinSpace, Atlas Obscura, HotelSpecials and Gelderlander)

(images via: JustinSpace, Atlas Obscura, HotelSpecials and Gelderlander)

Before Three Mile Island, however, nuclear power was seen by both governments and energy consumers as the way of the future. New types of reactors were designed, including the Fast Breeder reactor powered by plutonium and cooled by liquid sodium. One such fast breeder reactor (the SNR-300) was planned for Kalkar, a town in Germany close to the Belgian and Dutch borders.

(image via: PretparkVakanties)

(image via: PretparkVakanties)

Construction began in 1972 but as it progressed, concerns about the safety of the reactor and descriptions of the horrific consequences of an accident stoked a fierce backlash that forced authorities to cancel the project. What to do? The Kalkar complex sprawled over an area the size of 80 soccer fields and had enough wiring to circle the globe… twice.

(image via: Chip Fotowelt)

(image via: Chip Fotowelt)

A Dutch investor bought the site along with the infrastructure in 1991 and proceeded to turn it into Wunderland Kalkar. The outside of the cooling tower was painted with a cheery mountain mural while inside, a swing ride keeps park visitors happily screaming. Better that than the other kind of screaming, amiright?

![]()

(image via: DVD Set Shop)

(image via: DVD Set Shop)

Some might wonder if it’s appropriate to co-opt the arts in making large-scale power generation look more attractive. A few might even state that culture – pop or otherwise – has no business interacting with corporations who, when it comes to the environment, are part of the problem and not the solution. To those I say that it’s too late: coal and nuclear power have become part of our lives and those iconic cooling towers are as commonplace as donuts in a donut shop… mmm, donuts.