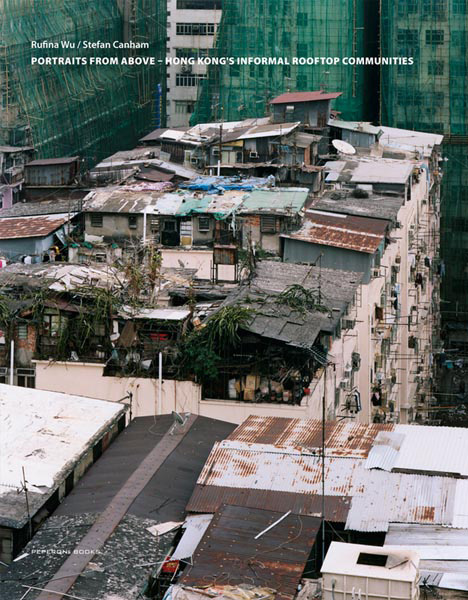

These hidden shanty towns, often invisible from the streets below, sprawl like surrealist suburbs across the roofs of one of the most densely-populated and expensive cities in the world.

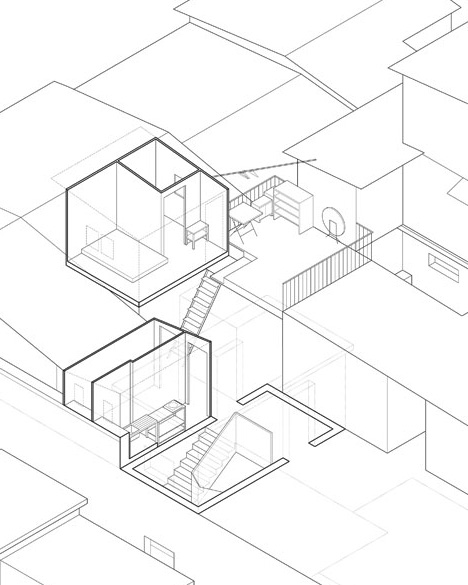

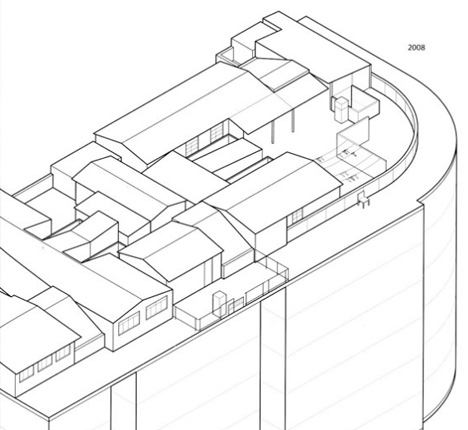

The book Portraits From Above meticulously documents a series of such informal micro-villages in Hong Kong with photographs, detailed diagrams and stories of life inside these illicit rooftop communities.

While the dwellings are unconventional in shape, the book’s drawings are almost deceptively refined, capturing the chaos in clean black-on-white architectural lines.

Ad hoc architecture at its strangest, these structures are not governed by building codes or compliance issues. Found materials from sheet metal and scrap wood to discarded plastic and broken brick shape home walls and the narrow halls between homes.

Naturally, one downside of such unplanned habitats are the series of power and waste management issues that go with the territory.

Despite living on the fringes – or perhaps because their shared connection – there are strong social ties between rooftop dwellers, and they were welcoming to the authors of this book, Stefan Canham and Rufina Wu, who sought to learn more about how people live in such offbeat accommodations. In many ways, too, these mini-cities are like smaller expressions of larger-scale phenomenon like the nearby but now-demolished Kowloon Walled City.

From the foreword: “There is no elevator. We run eight floors up the stairs … out of breath. The roof is a maze of corridors, narrow passageways between huts made of sheet metal, wood, brick and plastics. Steps and ladders leading up to a second level of huts. We get lost …. Rufina knocks on a door. A brief conversation in Cantonese. Stefan stands in the background, the foreigner, smiling, not understanding a word. They listen to us, smile and invite us into their homes. Later, we look from a high building on the other side of the street down at the building [we were on before]. The roof is huge, with thirty or forty households, like a village. From the outside it is impossible to guess what it looks like on the inside.”

Later, “We walk back up the stairs. We no longer get lost in the corridors. We learn how the residents rebuild their homes and keep [them] in good shape. There are people who live for twenty or thirty years on the roof[s]. The newcomers from China, Southeast Asia [and] Pakistan still do it …. Some underlying buildings slowly disintegrate, because the concrete was mixed with salt water. Most residents roof would not mind to live in one of the new high-rise buildings, but they can not afford it. All are afraid to be resettled in the satellite towns, where there are few prospects. The rooftop settlements are an urban legacy. They tell of the history of Hong Kong, the political upheavals in China, renovation, and demolition speculation, [structural] calculations and what people need to live in the city.”