Even the world’s most famous and celebrated architects have their failures, whether due to unforeseen consequences of an extraordinarily complex design or just plain shoddy construction. From the mold and cracks in Frank Lloyd Wright’s masterpiece Fallingwater to downright dangerous flying roof panels at Calatrava’s opera house in Valencia, these structural defects have led to injuries, lawsuits and in some cases, potential razing of a project before it’s even opened to the public. You can’t quite call these buildings outright failures just because they’ve got structural issues, especially since some of them are already iconic. But is this what happens when architects neglect practical considerations in favor of bold aesthetics?

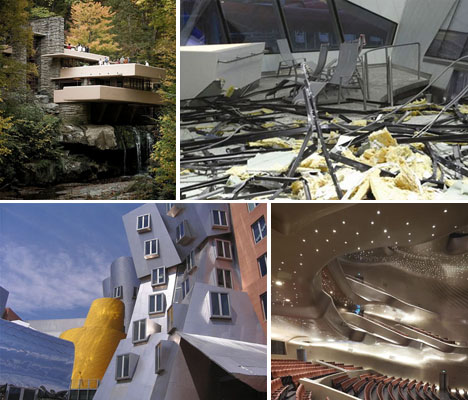

Mold and Structural Failures: Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater

The masterpiece of perhaps the only architect who’s a household name in America, Fallingwater by Frank Lloyd Wright was a fantasy home, a grand experiment that sought to push the boundaries of existing technology and building methods of the time. Cantilevered over a waterfall on Bear Run in rural Pennsylvania, the residence is undeniably stunning. Who wouldn’t want to live in a house perched right over the water, constantly filled with aquatic sounds and reflections? Anyone who’s ever dealt with mold. Fungal growth and excess humidity got so bad so quickly, owner Edgar Kaufmann nicknamed the house ‘Rising Mildew.’ And that’s just one of the major problems that began to plague the house almost immediately after it was built.

There were conflicts all along between Wright, Kaufmann and the contractors building the house and various elements were rebuilt several times. The cantilevers developed for the structure weren’t quite up to the task of holding it up, and the building started to deform before it was even complete in 1937. Two large cracks formed on the terrace’s parapet as soon as the formwork was removed. Wright insisted that the design didn’t require any kind of propping system, but by 1995, a deflection of 7″ was measured at the edge of the largest cantilever, along with a number of serious cracks. The Western Pennsylvania Conservancy, which owned it by that point as a museum, had to do an extensive restoration and add steel trusses to support the cantilevers. Of course, these problems hardly put a dent in the importance of this house’s impact on 20th century architecture, or in Wright’s legacy.

Roof Falling Off: Calatrava’s Palau de les Arts Reina Sofia Opera House, Valencia, Spain

Santiago Calatrava is best known for sweeping, bird-like designs that seem like they could lift up off the ground and fly away. His Palau de les Arts Reina Sofia Opera House in his hometown of Valencia, Spain is a perfect example of his signature style, with 14 above-ground stories and three below-ground, all covered in a curved roof reminiscent of a helmet. The tallest opera house in the world at 246 feet, it contains four auditoriums. Right after it opened to the public in 2005, a series of problems began to plague the structure: the main stage platform in the largest hall collapsed, forcing the cancellation of performances. Then, the complex was inundated with 7 feet of floodwaters, destroying electronic equipment in the lower levels.

But in early 2014, the city of Valencia filed suit against Calatrava for a more serious issue: sections of the mosaic roof began to come off in high winds, forcing authorities to cancel performances and close the building to the public. And this is just one among many lawsuits and accidents relating to Calatrava’s structures. A conference center he designed in Oviedo suffered structural collapse, his footbridge to the Guggenheim museum in Bilbao has required the city to pay out medical costs for dozens of pedestrians who slipped on the glass surface, and another footbridge over the Grand Canal in Venice has required ‘excessive repairs.’ Calatrava was also ordered to pay for the leaking roof of the Ysios Winery (pictured above.)

Leaking, Cracks and Falling Ice: Gehry’s Strata Center

This massive 720,000-square-foot academic complex for the Massachusetts Institute of Technology is known as the Ray and Maria Stata Center after its two primary donors, and houses the Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory in addition to other academic departments and offices for thinkers like Noam Chomsky. It would be hard for anyone who knows the slightest thing about architecture to miss the fact that it’s a Frank Gehry design, with its sharp angles and melange of metallic finishes. Like most of Gehry’s work, the structure is both praised and reviled – you either love it or you hate it. Gehry himself says it “looks like a party of drunken robots got together to celebrate.”

But MIT administrators have a less than glowing opinion of it for a different reason. The structure leaks, masonry has cracked, mold has developed, drainage has backed up and falling ice and debris repeatedly blocks emergency exits. MIT sued the architect in 2007, accusing him of negligence and breach of contract in the design of the center. Gehry’s response is that MIT is simply after his insurance money, stating “A building goes together with seven billion pieces of connective tissue. The chances of it getting done ever without something colliding or some misstep are small. I think the issues are fairly minor.”

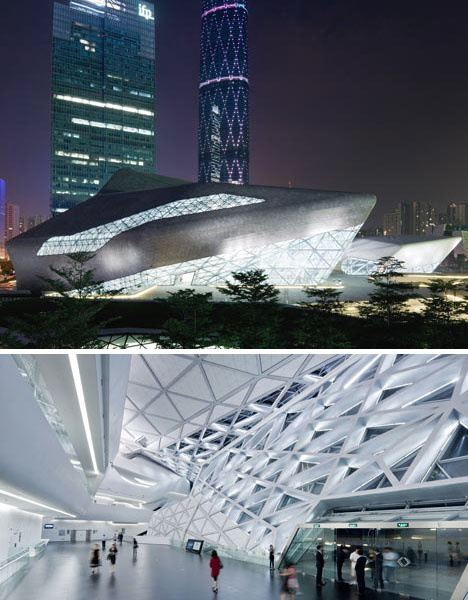

Falling Apart: Zaha Hadid’s Guangzhou Opera Center

Zaha Hadid’s Guangzhou Opera Center has been praised as the world’s most beautiful performing arts venue with a futuristic ‘twin boulder’ design on the edge of the Pearl River. Sharp angles, geometric patterns and stark white surfaces belie Hadid’s organic inspiration, taken from the geology and topography of the setting. Dotted with starry lighting, the main auditorium has a womb-like feel in gleaming gold. Unfortunately, just a single year after it opened to the public, the building was marred by falling glass and large cracks in the walls and ceilings, leading to serious leaks.

Like many of these ‘failures,’ the problem here isn’t so much Hadid’s design as it is the shoddy materials and construction techniques of the contractors that built it. Many of the 75,000 granite slabs that make up the exterior have begun to fall off, with some blaming poor quality craftsmanship and others blaming Guangzhou’s extraordinarily humid climate. But in China, deadlines to complete even the most complex buildings are often rushed, and a lot of architecture is built with the expectation that it will only stand for about 25 years. The construction group that built the opera center say that it was just extremely difficult to fulfill Hadid’s vision.