Seeing is believing… or is it? Aided by high-tech materials, today’s amazing 3D street graffiti artists, 3D mural painters and other clever geek artists. designers and architects are finding that if it can be imagined, it can also be built. This selection of architectural optical illusions showcases 20 more very public ways to fool the eye, please the mind and satisfy the soul.

(image via: Big Illusion)

(image via: Big Illusion)

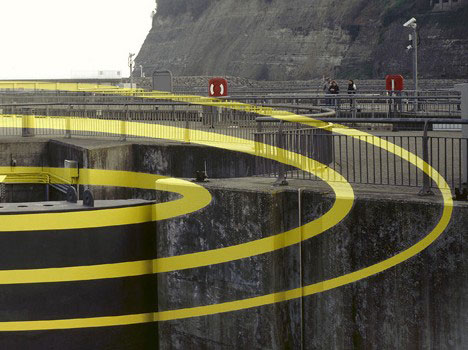

Artists like Felice Varini like to think big, and this installation is so vast it requires the aid of distance to complete the illusion. “Three Ellipses for Three Locks” in Cardiff, Wales, was completed in 2007 and proves that with a small amount of material – in this case, some yellow paint – something grand can emerge.

(image via: BBC)

(image via: BBC)

The piece is a classic “anamorphic illusion” in that to view Varini’s art as intended, one must be in a certain position where the sightlines can perfectly converge. Costing a mere $50,000, the work was one year in the planning stages yet took only two weeks to create.

(image via: 2Loop)

(image via: 2Loop)

Here’s another of Varini’s works, this time on a smaller scale and indoors. The effect is still effective at fooling the brain into seeing something that isn’t really there.

(image via: Panya Clark Espinal)

(image via: Panya Clark Espinal)

Panya Clark Espinal is another artist who, like Varini, plays with perspective to distract and delight. Espinal’s work is showcased at the Bayview station of Toronto’s Sheppard subway line.

(image via: Gargles)

(image via: Gargles)

Here’s another shot of an Espinal piece in the Bayview station, this time with an obliging human on hand to put the piece into perspective, as it were.

(image via: Die Strassenmaler)

(image via: Die Strassenmaler)

Anamorphic street art has been popular in Europe for years and is slowly beginning to arouse attention on this side of the pond. Manfred Stader and Edgar Muller are among the best known creators of this distinctive type of street art; an example of which is shown above from the annual Moose Jaw Prairie Arts Festival in Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan, Canada.

(image via: Die Strassenmaler)

(image via: Die Strassenmaler)

More of Stader & Muller’s magic was on display in the form of the above Johnnie Walker rum ad painted on a street in Taipei, Taiwan. This is one rare occasion where drinking and driving DO go together!

(image via: Die Strassenmaler)

(image via: Die Strassenmaler)

The above faux reflecting well shows Stader & Muller at their most astonishing – not only does the street painting take on the appearance of a real well, but within it one can see the image of a nearby church “reflected” in the painted water.

(image via: Julian Beever)

(image via: Julian Beever)

Julian Beever is another European street artist whose canvas is the pavement – plus the odd wall or two. Though not all of Beever’s art is anamorphic, it does seem to be his specialty. Note the “tiny” person sitting on the beer bottle cap above left; giving a hint as to the true nature of the design.

(image via: Julian Beever)

(image via: Julian Beever)

Here’s another of Beever’s masterpieces. It almost seems a shame to re-open the street to traffic once the artwork is complete, not to mention the fragility of his usual media: colored chalk.

(image via: Spluch)

(image via: Spluch)

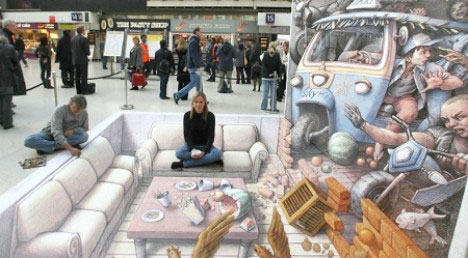

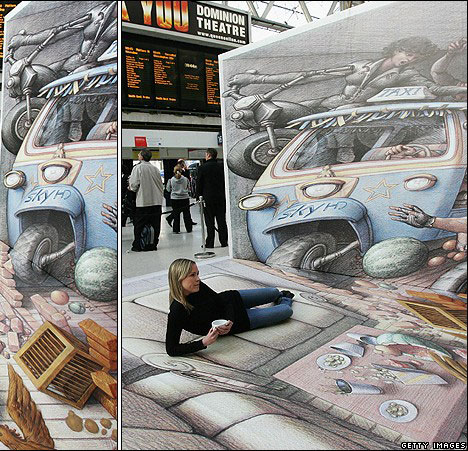

The above painting is by Kurt Wenner and is located at London’s Waterloo Station. Wenner cleverly uses both vertical and the horizontal planes to provide an extra jolt of unreality once the viewer reaches a certain optimal point on the station floor.

(image via: BBC)

(image via: BBC)

In this view, a 3D commuter named Tara Hicks helps bring out the 2D qualities of Wenner’s painting. The large and elaborate construction was commissioned by Sky, a satellite broadcasting company, as a way to advertise its new high definition service.

(image via: Neatorama)

(image via: Neatorama)

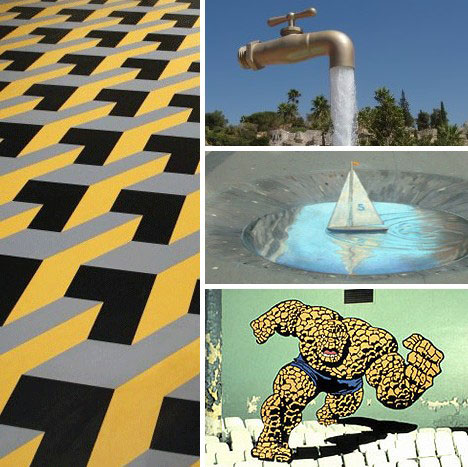

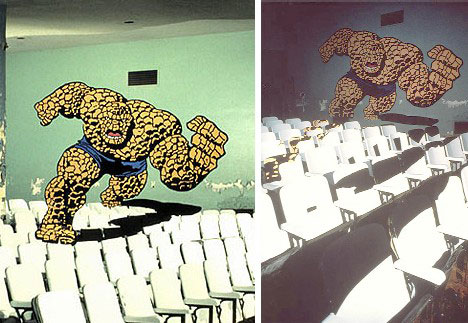

Another type of illusion is called Trompe l’oeil, French for “fool the eye”, and that’s just what happens when first encountering Justen Ladda’s The Thing, painted in 1981. For those who enjoy crowing “photoshopped!” at every opportunity, no amount of computer trickery can duplicate the scene Justin Ladda presents to visitors who walk into the decrepit former theater in The Bronx where The Thing awaits. Click on the link to get the full effect.

(image via: Think or Thwim)

(image via: Think or Thwim)

Even something as corporate as hotel carpeting can be energized by incorporating an optical illusion to create interest. Above is the new ballroom carpet being installed at the Marriott Solana hotel in Southlake, Texas. Thought the illusion will be lessened once chairs and tables are placed on the carpet, it’s still a bold move for the Marriott.

(image via: Illusions Etc.)

(image via: Illusions Etc.)

Other optical illusions are unintentional, like the above jet engine photo. It’s aid that by staring at the small white spiral painted on the engine’s spinner, the fan behind it will appear to move. For those wondring just why these little spirals are often painted at the centerpoints of jet engines, it’s so ground personnel can quickly see if the engine is on – when it is, the fan blades quickly blur but the eye catches the spiral endlessly spinning.

(image via: Spluch)

(image via: Spluch)

The so-called El Grifo Mágico, or Magic Tap, may be familiar though it’s more often seen in bars, as a seemingly endless flow from a beer can into a mug. This much larger version looks like something French surrealist Magritte might have painted, perhaps before taking a hot bath.

(image via: Leonzerider)

(image via: Leonzerider)

Pointe-Saint-Charles is a bridge in Montreal, Canada that appears as if it’s been used in an old Road Runner cartoon. The artist is uncredited but it’s refreshing to see an anonymous tagger break out of the graffiti-script box most of the others are locked into.

(image via: Recit de Voyages)

(image via: Recit de Voyages)

It’s also amusing to see that city authorities found it necessary to place a striped warning sign in front of the painted image. One might say it enhances the realism by extending the scene into reality.

(image via: PJLighthouse)

(image via: PJLighthouse)

Halfway around the world in Milan, Italy, a street named Via Padova features a very cool yet fully functional optical illusion.

(image via: PJLighthouse)

(image via: PJLighthouse)

To view the separate iron bar structures as an entire yellow bicycle one must stand at one of two exact viewpoints. To secure one’s bicycle, one must only roll up to one of the bars – from any angle – and affix a bike lock.

(image via: The Independent UK)

(image via: The Independent UK)

The late Juan Muñoz created The Wasteland, above, as an interactive piece that creates a sense of uncertainty in the mind of the beholder. Is the bronze statue at the far end of the room a prisoner or a master? Is the linoleum tile floor a jumbled field of interlocking blocks, or does it only look that way?

Optical illusions have a way of making us pause and ask questions about the very status of the reality we see – or appear to see. For artists like Juan Muñoz, that’s not a bad thing.