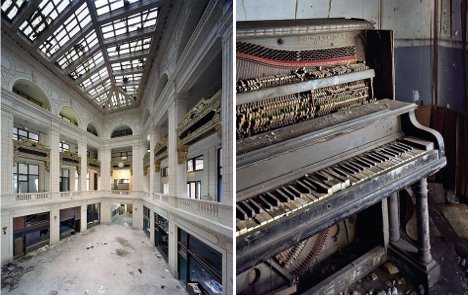

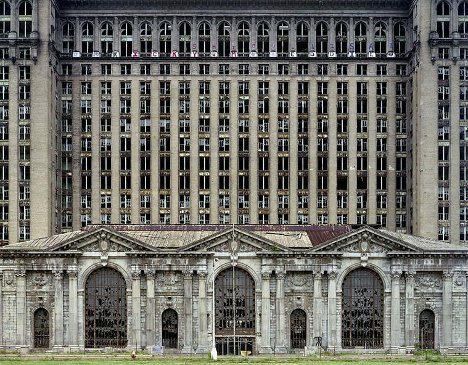

Detroit is arguably one of the most fascinating modern cities in the world. This is thanks to the city’s unique balance between its former identity as a manufacturing mecca and its current state of sectional abandonment and iterative renewal. It is neither deserted nor wholly occupied, but exists in tension between destruction, creation and everyday living, with beautiful stories on all of these fronts. French photographers Yves Marchand and Romain Meffre saw the abandoned parts of this compelling urban landscape as no less fascinating than the ruins of ancient civilizations and set out to document it in their 2010 book The Ruins of Detroit.

(all images via: Marchand Meffre)

Despite the empty neighborhoods, abandoned buildings and crumbling structures – or perhaps because of them – Detroit still possesses a kind of indomitable magic. The city exists in a state of flux, balancing somewhere between its former glory, its current semi-abandoned status, and pockets of fresh new life and creative directions springing up from the ashes.

The city, so rich with history both industrial and individual, was once the fourth largest in the United States. It housed some of the country’s brightest engineers and most promising entrepreneurs. The city grew and its residents continued to expand their living areas into planned suburbs.

But the automobile industry which had such a large part of the city’s early days also proved to play a part in its undoing. White middle-class residents used those automobiles to move out of the inner city and into their new suburbs. Segregation increased steadily until the violent race riot in 1967.

Following the riot, the city continued its rapid decline. The industry that built Detroit moved on to other locations. Inner-city residents fled their homes by the thousands. Every race and every economic class was affected by this exodus; the city simply bled away until it held less than half its former population.

Unlike almost any other place in the world, Detroit’s abandoned buildings and ruined structures are not isolated in one part of the city. Grand, well-kept buildings can exist just meters away from crumbling ruins. Inhabited and abandoned homes exist side by side in neighborhoods – this as tragic in some sense, but has also provided the seeds of fresh slates throughout the city. New projects happen rapidly in this fluid urban environemnt.

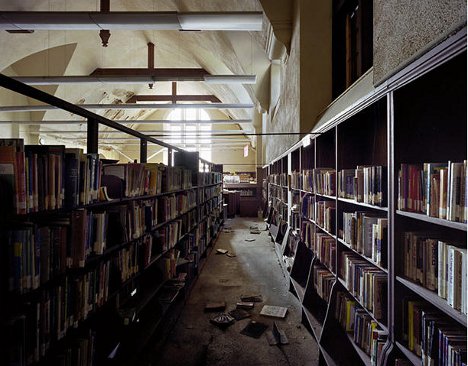

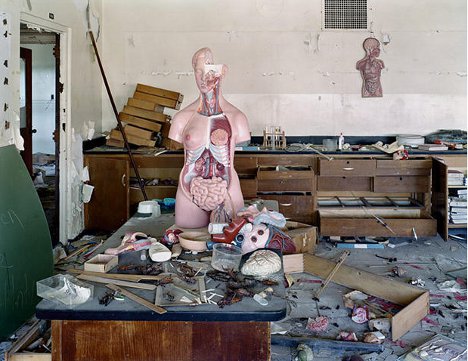

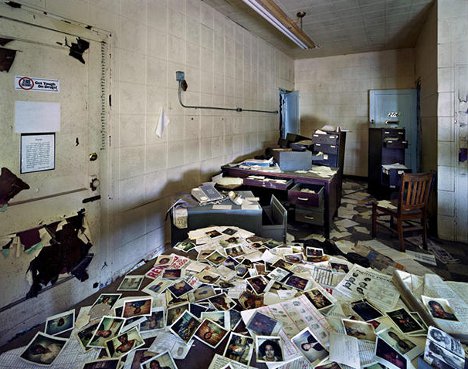

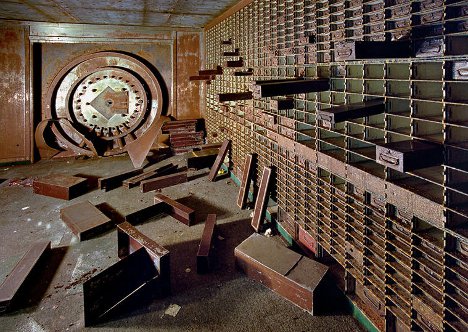

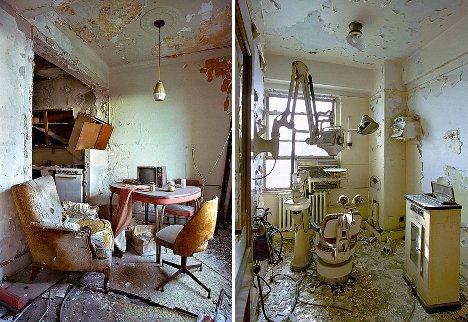

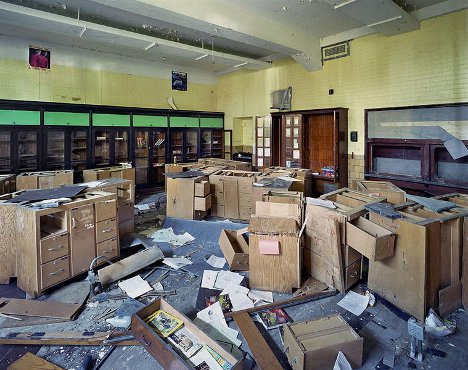

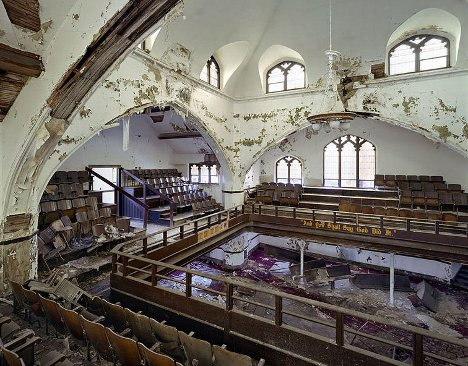

What is so compelling about the images in The Ruins of Detroit is the seeming urgency of the city’s abandonment. In civic buildings, papers and boxes still occupy offices. In abandoned libraries, books continue to line the walls. Schools still hold desks and police stations are stuffed with forgotten and moldering mug shots. Chairs are tipped over as though the former occupants of these buildings suddenly evacuated due to an emergency.

Given the slow but steady decline of the city’s population, this urgency is baffling. Surely there was more than enough time to clean the buildings out, remove anything that could be reused or salvaged and clean the buildings up. But it seems that no one cared to take the time to do so. Perhaps the reasons behind these rapid abandonments are lost to the ages. In some cases, however, the intact interiors can be transformed again when a new use is presented.

The photographers point out that this state of partial ruination is ephemeral – eventually it must give way to complete ruin or rebuilding. Their goal was to photograph the city’s current state of abandonment before fate tips one way or the other.

For the sake of everyone who has ever lived in or loved Detroit, there is and should hope that there is rebirth in the city’s future. The once-great city is still capable of captivating us with its strength and resilience if we only care to watch it bounce back. Already, new industries and urban plans have freer reign than in almost any other major city – projects shoot from start to finish with amazing speed.