Empty Chinese-Built Housing Development of Kilamba, Angola

(images via: angola non-profit)

The modern ghost town of Kilamba isn’t something you’d expect to find in Angola – indeed, it’s highly reminiscent of China’s ghost town of Ordos City. That’s because it was built by the China International Trust and Investment Corporation, financed by a Chinese credit line and repaid by the Angolan government with oil. The series of 750 eight-story apartment blocks, along with over 100 commercial complexes and a dozen schools, was designed to accommodate half a million people, but only a few hundred apartments were sold in the initial opening period, leaving the vast development empty for many months. Angola doesn’t have a large enough middle class to afford homes like this.

But as of summer 2013, the apartments are slowly filling up thanks to government subsidies lowering the price of each unit by nearly half. Like Ordos, it may be a challenge to get Kilamba up and running as the model for emerging economies that it was intended to be, but maybe its ghost town days are numbered.

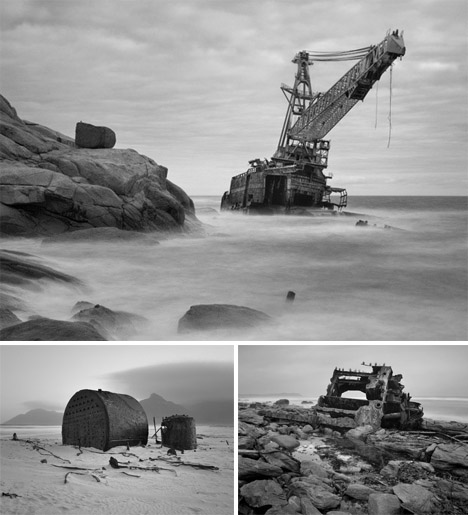

Ships and Machinery on the Cape of Good Hope, South Africa

(images via: dillon marsh)

Remains of shipwrecks and rusted machinery stretch out on the rocks of South Africa’s Cape of Good Hope like the carcasses of extinct beasts. Casualties of the extreme weather that gave the area the nickname Cape of Storms, these abandonments have been left to deteriorate as a reminder to sailors of just how perilous the waters can be. While the intersection of cold swells from Antarctica and a warm current of the Indian Ocean is responsible for most of the danger, the former lighthouse – which wasn’t quite tall enough to be of much use – certainly didn’t help. A 5,500-ton Portuguese ship called the Lusitania is among those to have wrecked here. The Cape is also the setting for the myth of The Flying Dutchman, a ghost ship doomed to sail the seas forever.

Grand-Bassam Ghost Town, Côte d’Ivoire

(images via: y-voir, wikimedia commons)

Once the French colonial capital city, Grand-Bassam remained a key seaport of Côte d’Ivoire until the ’30s. But as commercial shipping in the area declined, so did the population. At the time of the nation’s independence in 1960, even more residents left as remaining administrative offices were transferred elsewhere. For decades, Grand-Bassam was only inhabited by squatters – but the allure of French colonial ruins in an exotic seaside setting began to bring in foreign tourists in the 1970s. Sensing an opportunity, native Ivoirians began to move back to cater to the emerging industry. Today, just 5,000 people live in the town, and some areas remain abandoned. The crumbling ruins, some sprouting palm trees from their roofs, continue to be a draw for visitors.