There’s something really special about an architectural restoration project that takes the ruins of an old historic structure and visibly preserves them by integrating them into a more modern building – if it’s done right. But where’s the line between the ones that pull this off with subtlety and respect, and the ones that get compared to that botched ‘restoration’ of a Christ fresco by a well-meaning old woman? Some of these projects transforming crumbling ruins, rotting remains and abandonments into usable buildings are stunning, others perhaps less so – but it’s all relative. How would you judge these dramatic makeovers?

Casa Sabugo by Tagarro de Miguel Arquitectos

The wounds of a partially destroyed building are left visible as a major visual feature of a modern renovation in this project by Tagarro de Miguel Arquitectos. Set in a rural area overlooking an emerald meadow, the home features a new glass wall inserted into the ruins of an older structure for a dollhouse-like effect. “The project aimed to create a refuge that would highlight the humble beauty of simple things, imperfect, with memory, eroded by time,” say the architects. “An orderly chaos that invites us to go more slowly and see and taste more. A corner to forget and remember.”

300-Year-Old Home in England by David Connor Design and Kate Darby Architects

A cottage in England’s West Midlands that was close to crumbling is now preserved like a museum display inside a new envelope of black corrugated metal. David Connor Design and Kate Darby Architects simply built the new home around the ruins, keeping them intact as they were found with just a few modifications (like a new wood stove.) The result is stunning. “The strategy was not to renovate or repair the 300-year-old listed building, but to preserve it perfectly,” they say. “This would include the rotten timbers, the dead ivy, the old birds nests, the cobwebs and the existing dust. The ruins would be protected from the elements within a new high performance outer envelope. This means that in most places there would be two walls, two windows and two roofs, old and new.”

Tower of Vilharigues and Matrera Castle, Portugal by Carlos Quevedo Architects

The Vilhariques Tower and Matrera Castle in Spain underwent a restoration after parts of the important cultural heritage site suddenly slid to the ground in 2013 due to landslides. Built in the late ninth century, the ruins were pretty far gone by that point. Architect Carlos Quevedo used steel and cement to recreate the original dimensions of the structures, making the ruins accessible to the public again despite so little being left of them. Locals aren’t crazy about the result, though, calling it harsh and wondering whether its appearance is an intentional commentary on laws that require keeping a ruin ‘as is.’ Some even called it a “heritage massacre” and compared it to the infamous botched restoration of Elias Garcia Martinez’s fresco of Christ known as Ecce Homo.

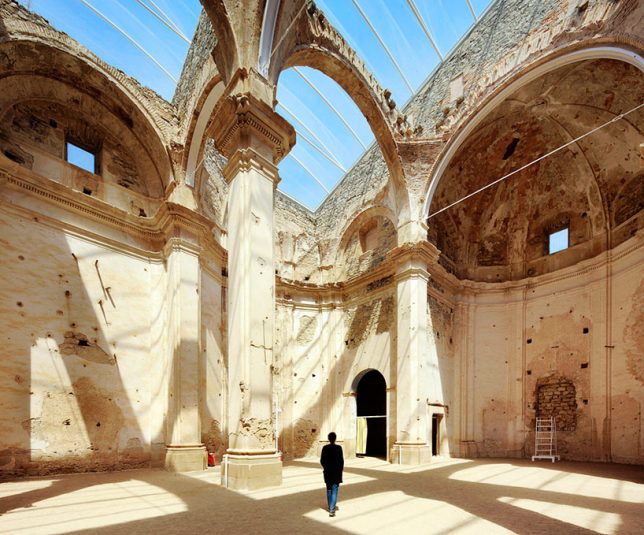

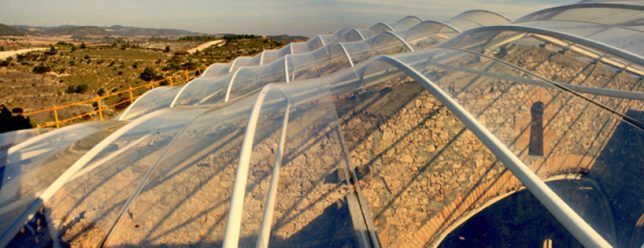

Church in Tarragona, Spain by Ferran Vizoso Architecture

A derelict church in Spain is now protected from the elements yet virtually unchanged thanks to a massive transparent roof acting like one big skylight. The roof structure on this town church in Corbera d’Ebre near Tarragona, Spain was totally gone – destroyed during the Spanish civil war – when the restoration started. Architect Ferran Vizoso wanted to make sure its history remained at the forefront. The solution uses ETFE panels to seal the interior and preserve the feeling of being outdoors while inside.

Santa Catalina de Badaya

The remnants of the old convent of Santa Catalina de Badaya in Basque, built in the 13th century, were vacated by the monks in 1835 and turned into a barracks for troops of the pretender to the Spanish throne, Carlos Maria Isidro de Borbon. In the midst of an ensuing conflict, the structure was set on fire and left in ruins. In 1999, a new project began to transform its shell into a stunning botanical garden. While it remains open, the project to transform it for a new use included reinforcing some of the walls with wood in a way that contrasts the old materials with the new.