Look at architectural renderings on a regular basis and soon you’ll start to spot stylized elements that pop up often enough to be called cliches, every one of them inserted into the image for a specific purpose. It’s all about selling the viewer on the concept, consciously and subconsciously, like any other form of marketing. The point of architectural renderings is typically to convince the client, the investors and the public at large that the project (and, specifically, the architect’s vision) deserves funding and support. They make it possible to envision what it will look like before ground is broken, not just visually but emotionally.

The best tactic to sell someone something, after all, is to appeal to their needs and desires. What does the public want out of a new museum or seaside park? How does a wealthy bachelor see himself in a new home? What can help convince investors that a project is prestigious enough to justify their participation? Sometimes it all comes down to a kid with a balloon, an otherworldly glow or lots and lots of fireworks.

The use of storytelling tools in architectural proposals certainly isn’t new. Back when they were all drawn by hand, renderings still had their tropes: a Zeppelin in the sky beside every tower, a futuristic skyline implying a certain cutting edge quality to the project. Today, there are enough digital tools to make the process of producing a convincing rendering easier than ever. Artists use programs like Revit and Sketchup along with Photoshop to depict architectural models in real world settings, often with photorealistic attention to detail. They can download packs of human figures dubbed “scalies” along with other elements like furniture, trees and kayaks.

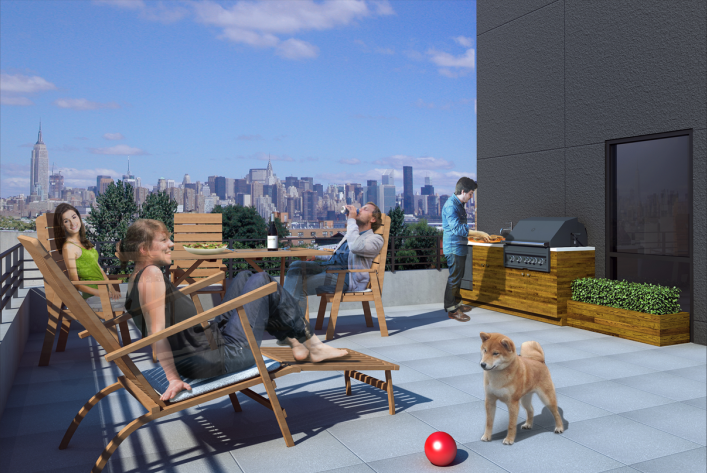

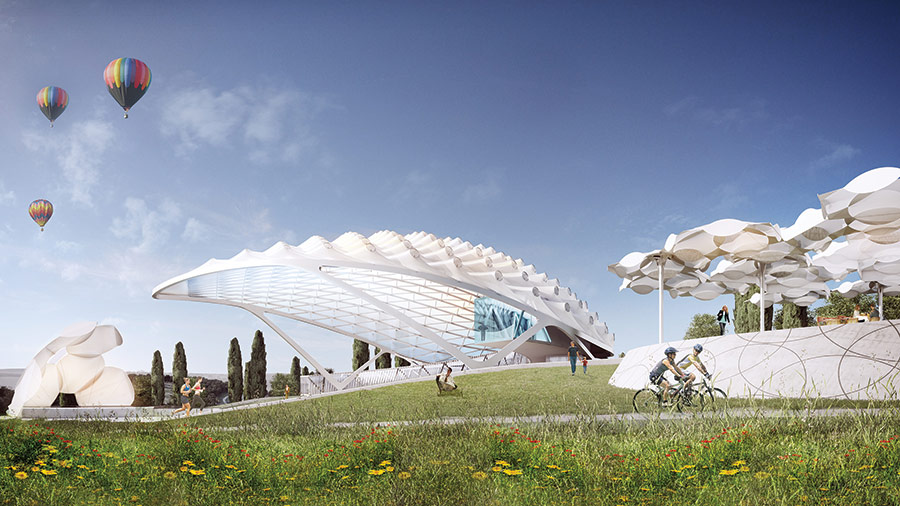

Yeah, about those kayaks. Renderings are selling us an idealized version of reality, and that often means plopping structures into sanitized fictional scenes straight out of a Norman Rockwell painting or 1950s-era Archie Comics. There might be far more kayaks than technically warranted in one image, but they’re showing us how fun, lively and adventurous that project could be. The same goes for bicycles, rollerblades and kites. Hot air balloons are a hell of a lot more ubiquitous in renderings than they are in real life. See how lively the scene is? Don’t you want to go there?

So-called “scalies” are fascinating in their own right. Sometimes they’re translucent to keep the focus on the building itself, giving them a ghostly quality. These, too, are all carefully chosen: mothers pushing babies in strollers, students lugging backpacks, businessmen striding with briefcases in hand, shoppers struggling with armloads of purchases. Supermodel types stand around in evening gowns for no apparent reason other than adding to the ambiance. As with any form of marketing, sometimes there’s a scantily clad woman just to catch your eye. It can almost become a game of Where’s Waldo.

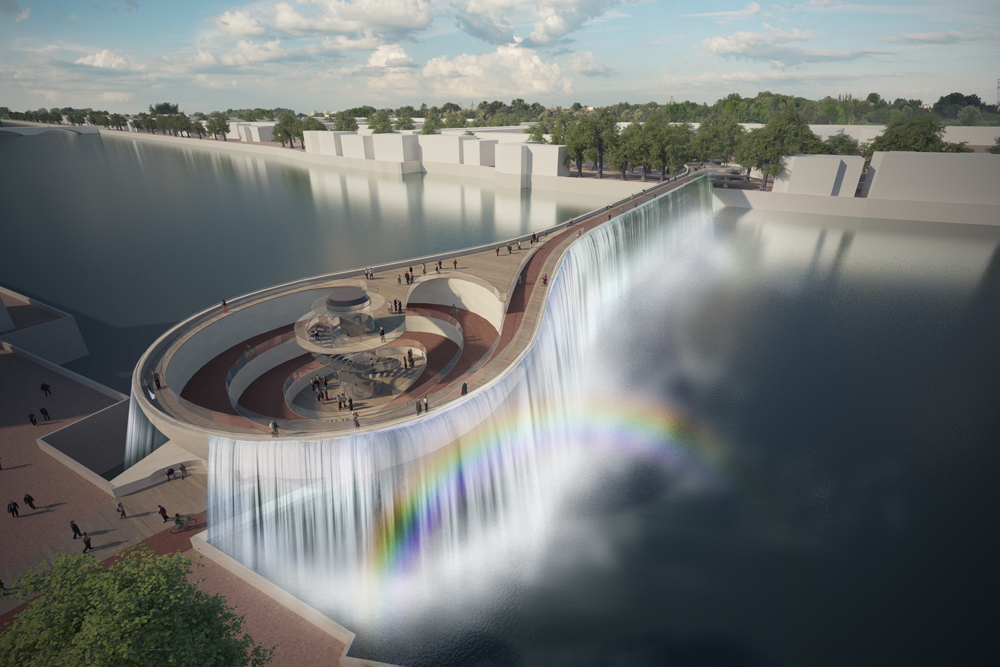

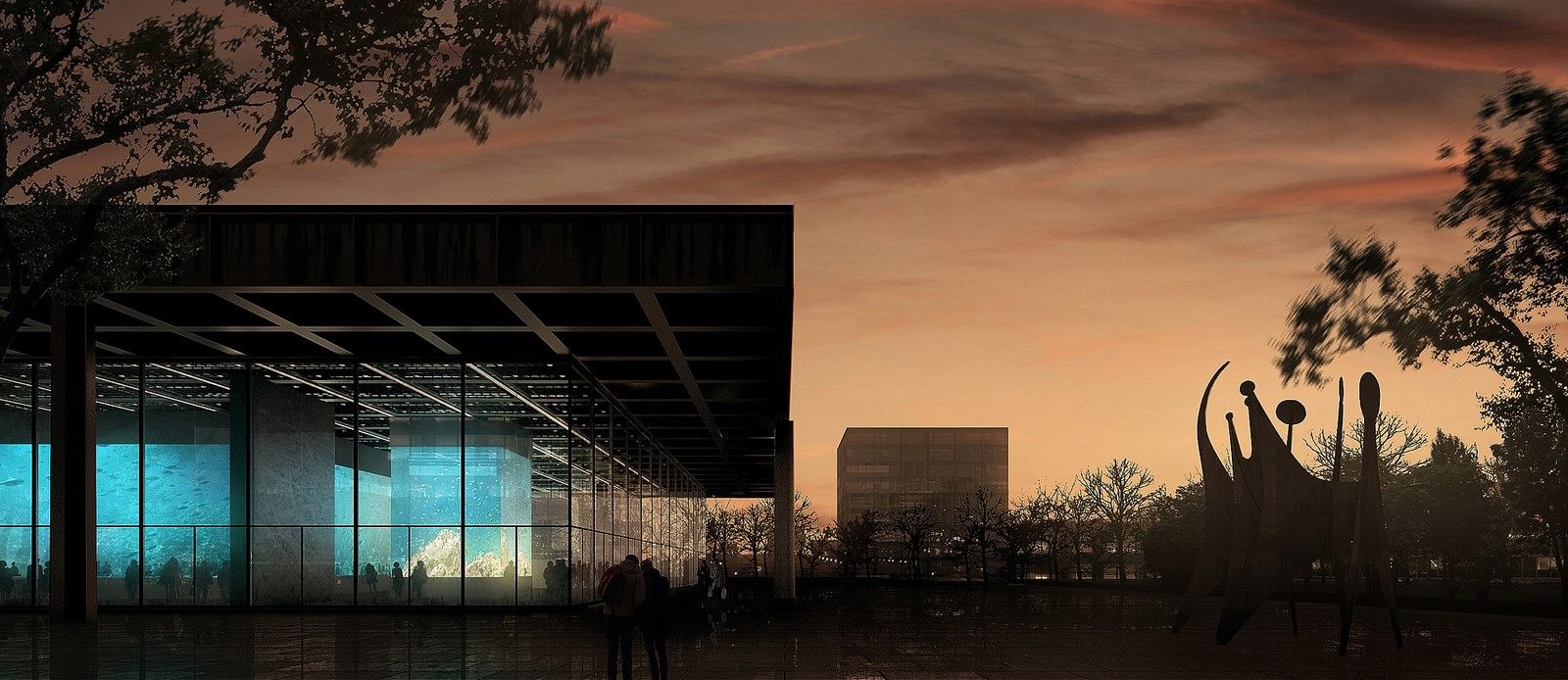

Then there’s the atmosphere. As crucial as lighting is to make a rendering realistic, sometimes designers just can’t resist adding all manner of effects to give the scene some extra shine. Lens flares and light trails are common, but even more egregious is the sort of artificial glow a building will never actually emit in real life. Glass facades are almost always portrayed as completely transparent in renderings when they’ll really be more like mirrors, changing the look of the structure altogether.

Overhead, there just happens to be a tranquil flock of birds, once again reinforcing the liveliness of the scene. The structure is so dazzling, wildlife is inexplicably drawn to it, even in the middle of the city. Maybe the structure is taken out of its real context and placed in a more pleasant setting, like a picturesque meadow.

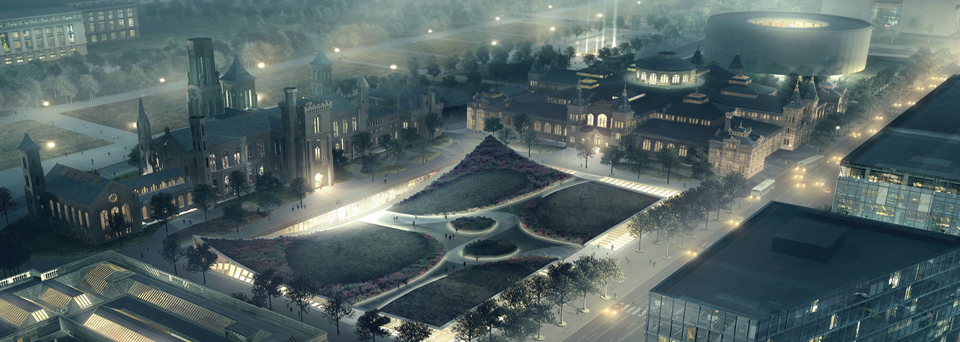

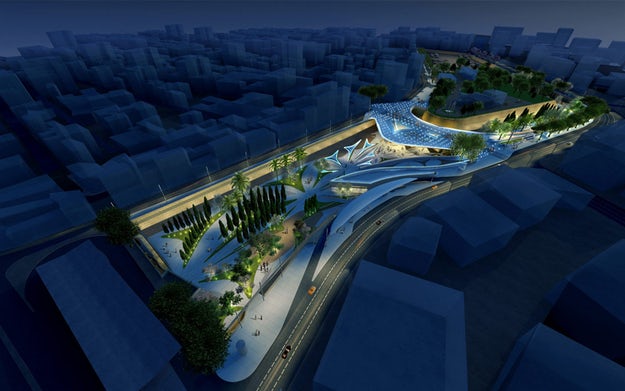

Many renderings depict the architectural model in color while the rest of the scene is in black and white, blurred or lacking in detail.

The point, obviously, is just to keep the focus on the proposal, but the effect can be unsettling, as if the rest of the neighborhood has fallen into ruin. Look how great that building is – everything else pales in contrast!

A dark, moody dystopian quality can even be applied intentionally to give the scene a cinematic sense of drama, lending it a gravitas it might not have under blue skies.

The ubiquity of these elements has spawned many a think piece as well as parodies, like a series of comics based on architectural renderings of Future Memphis. And once you start noticing them, you can never un-see them.

None of this is to say these rendering tropes should never be included, or don’t achieve what they set out to do – but it’s fun to examine the details, and prudent to question their purpose and discuss how potentially unrealistic imagery can set us up for disappointment once the projects are finally complete.