As cities grow and change, complex networks of elevated concrete highways and railways sprout up like vines, twist around each other and radically transform the space beneath them. Formerly vibrant urban districts are shrouded in darkness, and the potential to use that space is often wasted as officials fence it off or incorporate hostile features into the infrastructure to ward off loiterers and people lacking housing. Over time, some of those elevated roads might become obsolete, making the whole area feel like an urban wasteland.

But the need to make use of every available square foot of land is intensifying – and city planners working on the viaducts and overpasses of the future should probably take note of how that land is currently being reclaimed and rehabilitated to enhance its value to surrounding communities.

After the success of the High Line in New York City, an elevated linear park running along a former New York Central Railroad spur, many cities have begun transforming their own underpasses, viaducts, abandoned highway sections and even the tops of tunnels into verdant public spaces.

Atlanta’s BeltLine, Detroit’s Dequindre Cut and Washington D.C.’s planned 11th Street Bridge Park all demonstrate the how valuable the land can be to residents living nearby once it’s reactivated. These underpass parks can be surprisingly vibrant, like the 8-acre Underground at Ink Block park in Boston, Houston’s Sabine Promenade (top) or Toronto’s Bentway, which includes a 720-foot ice skate trail. Skate parks, like Portland’s Burnside ramps, are a natural fit.

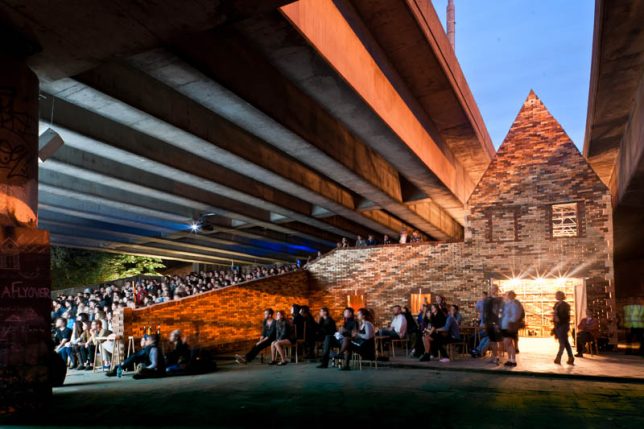

Art installations brighten up cavernous underpass spaces, whether with colorful lights like San Antonio’s temporary Ballroom Luminoso installation by JB Public Art or with oversized sculptural elements like the flowers of Glasgow’s Phoenix Park. Some underpass spaces draw regular crowds as venues for movies or events, like Folly for a Flyover by Assemble in Hackney Wick, England.

In Yokohama, Japan, a notorious red light district flourished beneath an overpass for decades before authorities wiped out it, turning a bustling (if crime-ridden) area into a ghost town virtually overnight. A recent redevelopment project called the Koganecho Centre tucks a complex of new buildings into this underutilized space to make it functional for residents in a new way, adding an art gallery, a cafe, a meeting space, an artist’s atelier and an open-air piazza to a 328-foot stretch under the concrete arches.

Housing can take shape around and beneath viaducts, too. In 2005, Zaha Hadid completed the Spittelau Viaducts Housing Project as part of a waterside revitalization scheme in Vienna, Austria. A three-part structure of apartments, offices and artist studios winds through, around and beneath a disused railway viaduct, playfully interacting with it while creating a contrast between old and new. Even tiny slivers of land beside viaducts can avoid feeling dwarfed, darkened and constrained by the infrastructure when cleverly designed, like the narrow Archway Studios live-work space by Undercurrent Architects or the Koops Mill mixed-use development occupying a former brownfield (both in London.)

Unfortunately, even when they become magnets for pedestrians, cyclists, families and tourists, these urban revitalization projects aren’t all sunshine and rainbow bike racks. Some of them perpetuate cycles of displacement, pushing low-income and other marginalized populations further away from amenities instead of serving them. Urban infrastructure projects are often built in poorer areas of town in the first place.

Transforming empty space into parks and venues might improve them, but it might attract deeper-pocketed buyers to the area, too. The High Line, for example, is currently struggling to make up for the imbalances it has created in once-affordable areas of Manhattan’s Chelsea neighborhood. Incentivizing affordable housing developments along with all the other elements of an underpass or viaduct makeover could help build equity into these projects from the beginning phases.