Aqueducts, those most triumphal examples of Roman arched architecture, have been displaying the engineering genius of the ancients for tens of centuries. These spectacular monuments not only spanned rivers and valleys to provide Roman cities with precious drinking water, aqueducts also spanned the length and breadth of Rome‘s far-flung empire. Here are 15 of the most noteworthy survivors.

The Park of the Aqueducts, Rome, Italy

(images via: University of St.Thomas, Insane, Montalbon and LA Times)

(images via: University of St.Thomas, Insane, Montalbon and LA Times)

It’s been said that “all roads lead to Rome” but the same might be said about aqueducts. Ancient Rome had a population of just over 1 million and on hot summer days, it takes more than bread and circuses to cool off a public inflamed by a gladiatorial doubleheader at the Colosseum. During the Middle Ages, Rome’s population dropped to around 30,000 – due in no small part to water shortages caused by the decay of the Eternal City’s life-giving aqueducts. The remains of several of Rome’s largest aqueducts can be seen, up close and personal, at The Park of The Aqueducts.

(image via: Wikimedia)

(image via: Wikimedia)

A common theme of art’s Romantic Age was the decline and fall of Ancient Rome. Painters such as Thomas Cole sought to express the weight of history and the loss of wisdom embodied in the fall of Rome by painting the remnants of the Empire’s largest and most visible examples of monumental architecture, the aqueducts. Above is “Roman Campagna (Ruins of Aqueducts in the Campagna di Roma)”, painted by Cole in 1843.

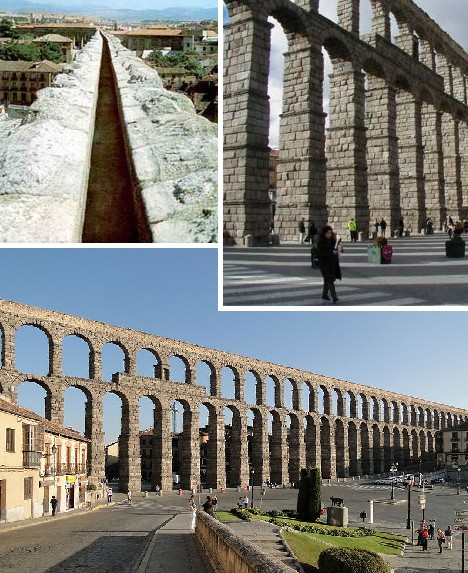

Aqueduct of Segovia, Spain

(image via: Cinque Terre Liguria)

(image via: Cinque Terre Liguria)

The Aqueduct of Segovia is one of the best-preserved Roman aqueducts in Spain. So well-built was the aqueduct and so studious its maintenance through the Middle Ages that it functioned as a viable water delivery system well into the 20th century.

(images via: Fotografias and Wikimedia)

(images via: Fotografias and Wikimedia)

The aqueduct features a total of 167 arches and the granite blocks used in its construction were assembled without the use of mortar.

(image via: Sacred Destinations)

(image via: Sacred Destinations)

The aqueduct was repaired in the year 1072 and again in the late 15th century on the orders of Spain’s ruling couple, Ferdinand and Isabella. At that time it was specified that the original visual style and construction techniques be followed to the letter. Currently undergoing repair and restoration, the Aqueduct of Segovia is a valued city and state cultural landmark that showcases the vast skill of Roman engineers nearly 2,000 years ago.

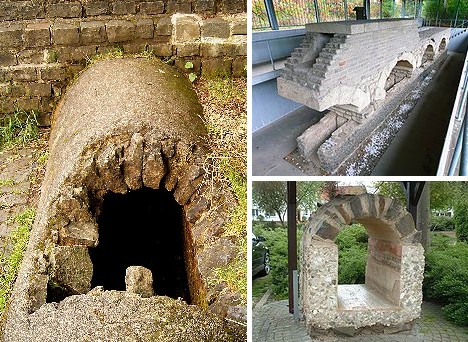

Eifel Aqueduct, Koln, Germany

(images via: D.E.A and Wikipedia)

(images via: D.E.A and Wikipedia)

The Eifel Aqueduct was built in 80 AD to provide the Roman city of Colonia Claudia Ara Agrippinensium (today’s Cologne) with fresh water. The entire system stretched across 95 kilometers (59 miles) to tap springs in Germany’s Eifel region. Most of the aqueduct was built underground to minimize damage, vandalism (perhaps from actual Vandals) and freezing in winter.

(image via: Stephanie Klocke)

(image via: Stephanie Klocke)

The few above-ground sections of the Eifel Aqueduct that remain show complex and skillful construction methods using brick and stone masonry that would not be matched in central Europe for many centuries. Curiously, medieval craftsmen would remove the calcium carbonate scale that accumulated in the inner walls of the aqueduct and reuse it as a sort of faux marble called Eifel Stone.

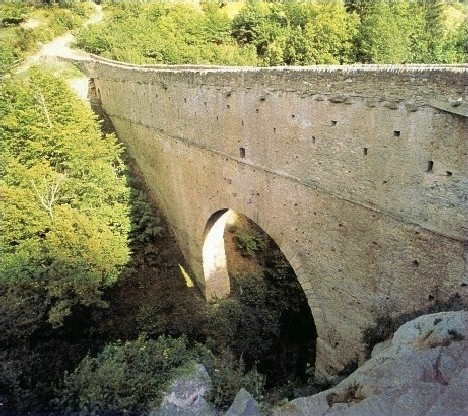

Pont d’Aël, Cogne, Italy

(images via: Postecode and Aymavilles)

(images via: Postecode and Aymavilles)

The Pont d’Aël is a practical combination of an aqueduct and a bridge. Located near Aosta in northern Italy, the Pont d’Aël was part of a 6 km (3.7 mile) long aqueduct that brought water to the newly founded Roman farming colony of Augusta Prætoria Salassorum; today’s Aosta. The original structure dates from the year 3 BC and rises 66 meters (216.5 ft) above the Aosta Valley.

(image via: Dilia Splinder)

(image via: Dilia Splinder)

Unusually, the Pont d’Aël and its associated waterworks were not financed by the state; instead the venture was privately planned and funded by Caius Avillius Caimus, a wealthy citizen from the city of Patavium (Padua).

Plovdiv Aqueduct, Bulgaria

(image via: Structurae)

(image via: Structurae)

Founded by the ancient Macedonians and named Philippopolis, today’s Plovdiv, Bulgaria was renamed Trimontium by the Romans as a nod to the three main hills that dominate the city. The Balkans as a whole were a critically important part of the Roman Empire and the regions towns and cities often hosted garrisons of legionaries to ensure invaders would be rebuffed. Trimontium was no different, and aqueducts were used to provide a secure flow of fresh water that would not be disrupted should the city fall under siege. Little is left of Trimontium’s aqueduct but the short section that still stands displays a quite modern beauty highlighted by the pleasing use of red brick and white local stone.

Aqueduct of the Gier, Lyon, France

(images via: France-Voyage, Virtual Globetrotting and Giorgio Temporelli)

(images via: France-Voyage, Virtual Globetrotting and Giorgio Temporelli)

The Aqueduct of the Gier is one of the longest and most complex Roman aqueducts. Utilizing tunnels, covered concrete culverts and classic raised sections over a sinuous path that stretches over 85 km (52 miles). The aqueduct was built over a period of several years at least in the first century AD and brought water to the Roman city of Lugdunum; now Lyon in eastern France.

(image via: Wilke Schram)

(image via: Wilke Schram)

The Romans were brilliant hydrological engineers and investigation of the inner workings of the Aqueduct of the Gier reveals the extensive use of soldered and pressurized lead pipes, holding tanks, siphons and manholes provided for maintenance.

Aqüeducte de les Ferreres, Tarragonna, Catalonia (Spain)

(image via: Xtec)

(image via: Xtec)

The Aqüeducte de les Ferreres (also known as Pont del Diable in Catalan and Devil’s Bridge in English) is a spectacular, 249 meter (817 ft) long aqueduct built around the year 0 in the reign of the first Roman emperor Augustus.

(images via: Academic.ru and Serrallenc)

(images via: Academic.ru and Serrallenc)

The 27 meter (88.5 ft) high structure was built to bring fresh water to the Roman city of Tarraco, today Tarragona in Spain’s autonomous region of Catalonia. In the year 2000, UNESCO added the Aqüeducte de les Ferreres to its listing of World Heritage sites.

(image via: Cinque Terre Liguria)

(image via: Cinque Terre Liguria)

Here’s a short video featuring the Aqüeducte de les Ferreres in all its glory:

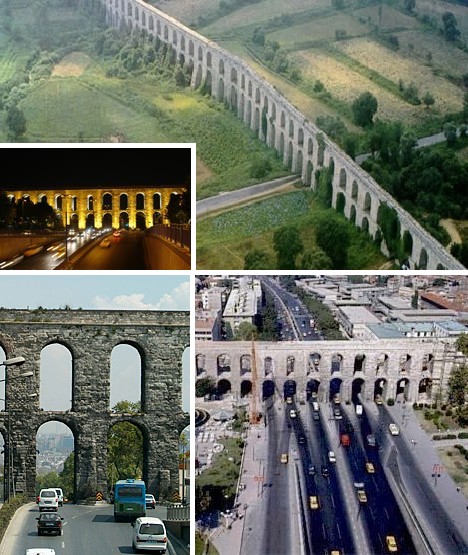

Valens Aqueduct (Bozdogan Kemeri), Istanbul, Turkey

(images via: New Istanbul Times and Guides of Istanbul)

(images via: New Istanbul Times and Guides of Istanbul)

The Valens Aqueduct, or Bozdogan in Turkish, was one of the main aqueducts supplying water to the capital of Byzantium, Constantinople. Such was the importance (and structural integrity) of this aqueduct that after the great city fell to Ottoman invaders in 1453, the occupiers repaired and maintained the aqueduct which today is a prominent part of Istanbul’s infrastructure. The aqueduct was built during the reign of Emperor Valens (364–378 AD) and was still functioning, albeit at a much-reduced capacity, into the early 18th century.

(image via: Achudinov)

(image via: Achudinov)

During the 1940s, Istanbul city planners were faced with a conundrum when designing the route of Ataturk Boulevard, which would intersect with an existing segment of the Valens Aqueduct. Thankfully, a solution was found by which the boulevard passed under the aqueduct’s arches without disturbing its foundations. Subsequent repairs, cleaning and strengthening have ensured the underpass is safe for both citizenry and history.

Herod’s Aqueduct, Caesarea, Israel

(images via: Works For Christ, Inner Faith Travel, Teach All Nations and Vintage Posters)

(images via: Works For Christ, Inner Faith Travel, Teach All Nations and Vintage Posters)

The Roman port of Caesarea on Israel’s Mediterranean coast was a major center of administration during the early years of the 1st millennium – the only problem was it did not have a constant and reliable source of fresh water. The solution was to construct an aqueduct that brought fresh spring water from the slopes of Mount Carmel, 16 k (about 10 miles) away.

(image via: Corbis)

(image via: Corbis)

Called Herod’s Aqueduct after the Judean king who commissioned it, the structure features arched pillars typical of Roman-era construction but hugs the ground as the area’s terrain was mainly flat. The aqueduct also may appear somewhat squat; this is due to an expansion performed in the 2nd century AD that widened Herod’s original design to carry two parallel water channels and thus increase the aqueduct’s capacity.

Moria Aqueduct, Lesbos, Greece

(images via: Harald Voglhuber and Agni Travel)

(images via: Harald Voglhuber and Agni Travel)

The remains of the Roman aqueduct near Moria on the Greek island of Lesbos are striking in their combination of delicacy and strength. Architectural masters of the ancient world, the Romans perfected the structural arch to the point that many of their grandest monuments required no mortar to hold the stones together. The Moria Aqueduct was constructed mainly of locally quarried marble.

(image via: Los Chu-Chus)

(image via: Los Chu-Chus)

The Moria Aqueduct supplied approximately 127,000 cubic meters (33,528,000 gallons) of fresh spring water per day to the Roman city of Mytilene. Precise inclination of the aqueduct’s water course over its original 22 km (13.7 mile) length ensured that water arrived at a slow and steady rate – as with all Roman aqueducts, an exceptional feat of hydrological engineering!

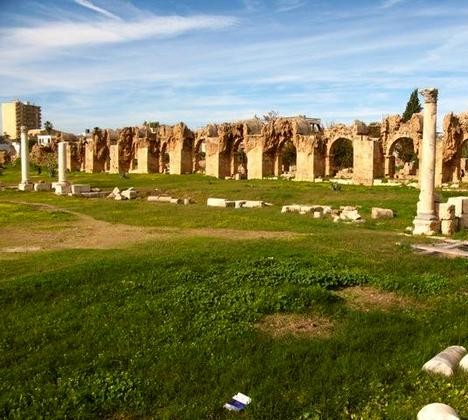

Aqueduct of Tyre, Lebanon

(images via: Virtual Tourist and Worship Excellence)

(images via: Virtual Tourist and Worship Excellence)

Tyre was founded by the Phoenicians in the 9th century BC on an island just off the coast of today’s Lebanon. The city’s claim to fame in the ancient world was Tyrian Purple, a brilliant violet dye made from a certain species of snail. Long invulnerable to attack, the city was finally conquered by Alexander the Great and revived by the Romans. Most of the monumental architecture visible at Tyre today dates from the Roman period (2nd to 6th century AD).

(image via: Virtual Tourist)

(image via: Virtual Tourist)

An island city in the sea requires fresh water to support its population, and the remains of Tyre’s aqueduct can be seen running along its former main avenue which leads to a massive triumphal arch.

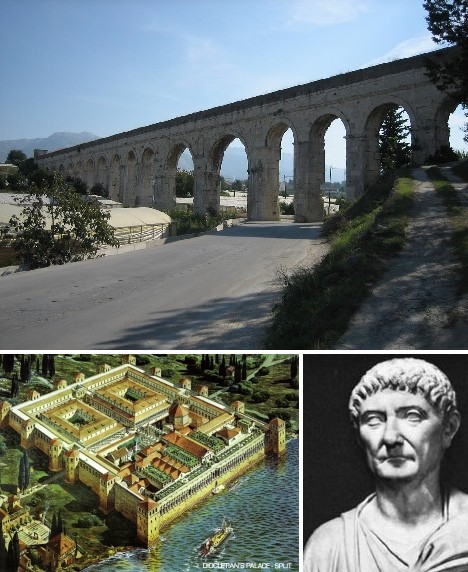

Diocletian’s Aqueduct, Split, Croatia

(images via: Skyscraper City, Andrew Petcher and All Empires)

(images via: Skyscraper City, Andrew Petcher and All Empires)

Diocletian’s Aqueduct in what is the modern city of Split, Croatia, was one of the last large aqueducts built in the Roman Empire. Estimated to have been completed in the first few years of the 4th century AD, the aqueduct was 9 km (5.6 miles) long and brought fresh water from the Jaso river directly to the massive palatial complex in the center of the city of Spalatum where the Roman Emperor Diocletian lived after his retirement.

(image via: Snjezana Novak)

(image via: Snjezana Novak)

The best-preserved portion of Diocletian’s Aqueduct can be found near Dujmova?a where a 180 meter (590.5 ft) section stands 16.5 meters (54 feet) high. Not too shabby for a guy who lived out the remaining few years of his life gardening and growing vegetables.

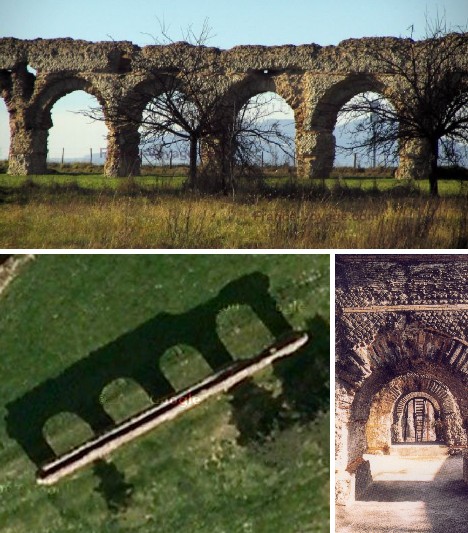

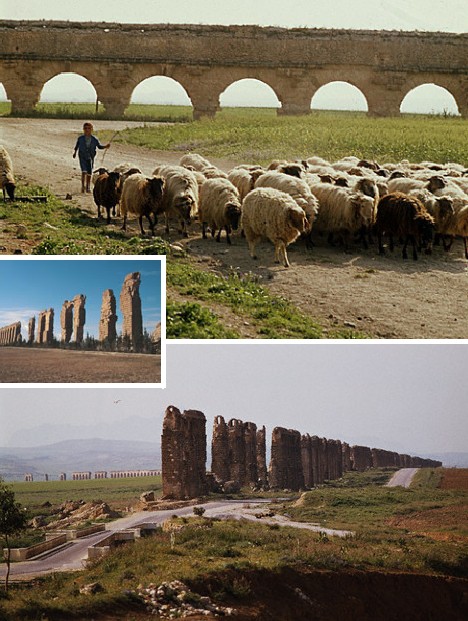

Zaghouan-Carthage Aqueduct, Tunisia

(images via: Corbis and Corbis)

(images via: Corbis and Corbis)

One of the longest aqueducts ever built anywhere in the Roman Empire marched across the arid plains of Tunisia, bringing life-giving water to the refounded city of Carthage. Some of the Zaghouan-Carthage Aqueduct‘s 132 km (82 mile) course has succumbed to the ravages of time, leaving only a line of pillars reminiscent of those at Stonehenge.

(image via: Corbis)

(image via: Corbis)

The Carthage of Hannibal lost a hard-fought, bitter war to the Roman Republic early in the second century BC that ended with the city being completely destroyed. It wasn’t long, however, before Rome realized the advantages of re-establishing Carthage as a Roman city and upon doing so, its population swelled to an estimated 500,000. Building the Zaghouan-Carthage Aqueduct was essential to provide the colonists with water for domestic and agricultural use.

Acueducto de los Milagros, Mérida, Spain

(images via: Fotopedia)

(images via: Fotopedia)

Of the three main aqueducts built by the Roman’s to supply the city of Emerita Augusta (Mérida, today) with water, Los Milagros (The Miracles) is the largest and best preserved. It is thought that the aqueduct was constructed in the 1st century AD with further work performed at the beginning of the 4th century AD.

(image via: Urbanity)

(image via: Urbanity)

Los Milagros drew water from an artificial lake formed by the damming of several small rivers. The aqueduct itself utilized a double-arcade format and the stonework was mainly granite blocks interspersed with stripe-like layers or contrasting red brick. Only 38 of the aqueduct’s 25 meter (82 ft) high pillars remain but the ruins still evoke a powerful sense of ethereal beauty and wonder.

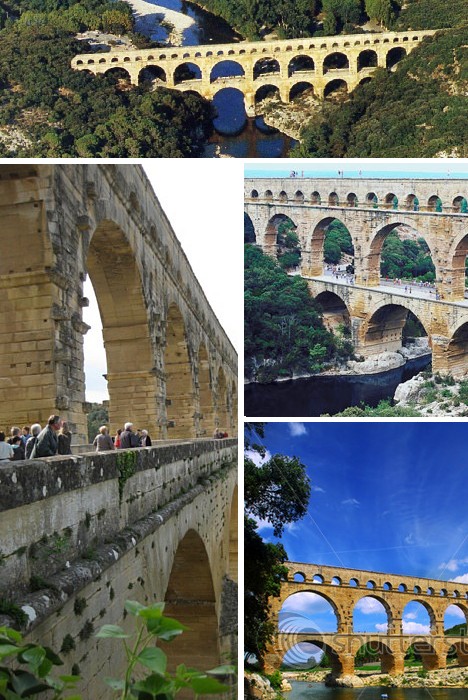

Pont du Gard, Nimes, France

(image via: Wallpaper Web)

(image via: Wallpaper Web)

Perhaps the most beautiful and most complete large Roman aqueduct is not found in Rome, nor the whole of Italy – it’s in the neighboring country of France. The ancient Roman Aqueduct of Le Pont du Gard is 2,000 years old (more or less; experts can’t agree) and was built to bring water to the Roman city of Nemausus (today’s Nîmes) from the Fontaines d’Eure springs near the town of Uzès.

(images via: Le Clus des Romarins, Travelpod and Globus Journeys)

(images via: Le Clus des Romarins, Travelpod and Globus Journeys)

What is known today as the Pont du Gard is actually only a portion of a much longer system of aqueducts stretching nearly 50 km (31 miles) in length. In its prime the aqueduct delivered as much as 20,000 cubic meters (5 million gallons) of water to the Castellum of Nemausus daily.

(image via: Real Daily Photo)

(image via: Real Daily Photo)

The Pont du Gard was made a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1985, and this worn relic of an ancient empire is more than deserving of the honor. You’ve got to hand it to the Romans: without the aid of computers, motors, electricity or even paper they managed to construct large-scale, precisely engineered “machines” that functioned perfectly precisely for centuries. Just like your Mom’s Buick… not.

![]()

(image via: Riding Brazil)

(image via: Riding Brazil)

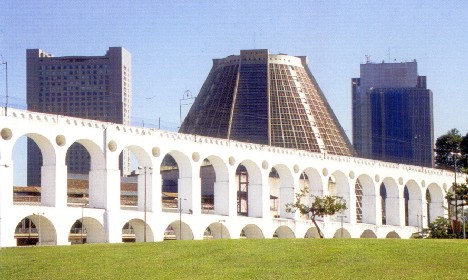

Outwardly lacy and delicate yet designed with inward strength, the survival of so many Roman aqueducts built up to 2,000 years ago – and in many cases, built without mortar to hold their stones together – seems almost miraculous. Not so much, really: the more you learn about the Romans, the more their profound skill, knowledge and insight can be appreciated. One wonders how many of OUR civilization’s monumental architectural works will still be around two thousand years hence.