When historic structures have fallen into ruin, should architects restore them to their original glory or acknowledge the passage of time? The answer to that question might depend on the significance of the building (and whether or not it’s legally protected), its condition and the client’s vision for its new purpose, but projects that take on this task run the gamut from painstakingly minimalist interventions to dazzling contrasts of old and new. A variety of approaches give new hope to buildings that seem beyond repair, even when all that’s left is a pile of rubble.

Minimal Interventions

Sometimes, the best solution is to allow the ruins to be what they are while adding some functionality back to the structure. These new additions might only include elements that make the building safer and more usable, or they might exert some architectural style of their own, standing out as contemporary against the aged stone.

In the case of Pi des Catalá Tower, a protected landmark on the smallest of Spain’s Balearic Islands, architect Maria Castelló Martínez made interventions “involving only the parts that jeopardized the life of the building most of all.” Local sandstone almost identical to the original materials fills in some damaged areas without hiding the chronological differences between the original substrate and the intervention process. Corten steel contrasts yet complements, reinforcing the doorways and windows, weathering along with the rest of the structure.

From afar, you might not even notice that anything has been added to these 700-year-old medieval ruins in Eastern Jutland, Denmark. Only from certain angles do the new observational staircase elements by MAP Architects become apparent, poking out of the crumbling brick. Visitors can take in the way time has altered the original structure of Kalø Castle from the zig-zagging staircase and use their imaginations to fill in the blanks. To make sure the ruins were up to the task of supporting the new staircase, the architects digitally scanned every individual brick with a portable 3D scanner, and only attached it to the ruins at four integral points.

The 16th century Blencowe Hall in England was added to the national ‘Buildings at Risk’ register after the roofs collapsed in the towers flanking either end, producing a large gash in the facade. Working with the owners and a local architect, Donald Insall Associates re-roofed the building, stabilized threatened areas and inserted a new facade behind the gash without attempting to close it up or hide it. The result is striking, especially at night.

Preserving Ruins As They Are

A 300-year-old cottage has been saved from falling into total ruin by a highly unconventional renovation you’d expect to see in a museum rather than a functional home. David Connor Design and Kate Darby Architects left almost everything intact, enveloping it all within a protective new shell.

“The strategy was not to renovate or repair the 300-year-old listed building, but to preserve it perfectly,” they say. “This would include the rotten timbers, the dead ivy, the old birds nests, the cobwebs and the existing dust. The ruins would be protected from the elements within a new high performance outer envelope. This means that in most places there would be two walls, two windows and two roofs, old and new.”

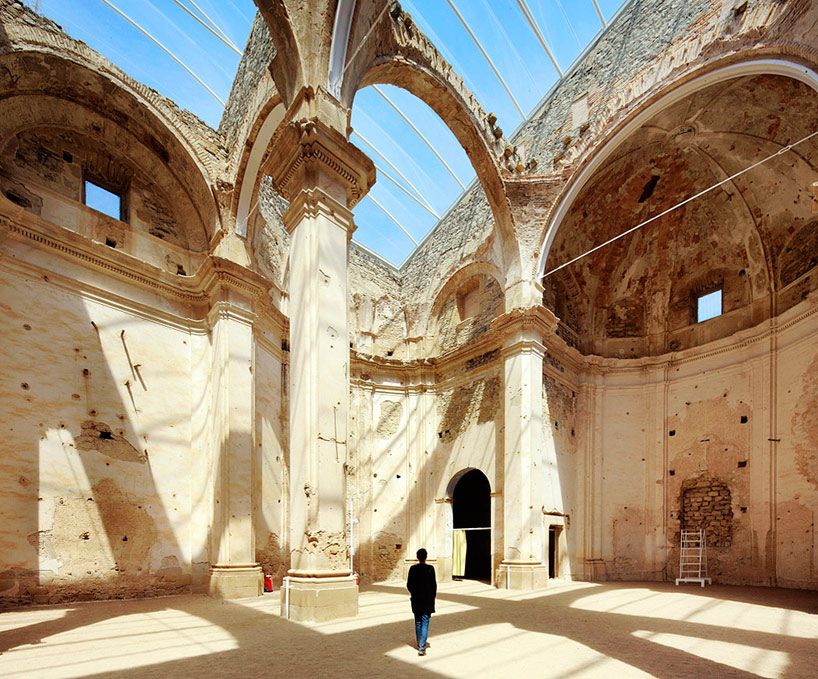

Ferran Vizoso Architecture took a similar approach with a church in Corbrera d’ebro, Spain. A new, lightweight contemporary membrane made of ETFE panels covers the vulnerable open roof to keep the building from deteriorating further, but in this case, the protective element is barely visible from outside. The windows have been enclosed, as well, creating a newly re-inhabitable space. Other reinforcements, like metal supports under fragile archways, are subtle enough to escape notice.

Ruins as Facades for New Houses

Whereas that English cottage preservation was virtually turned inside-out, with new construction on the outside, a more popular technique for restoring ruins keeps the outer appearance of the original structures intact while placing all interventions inside. If the dilapidated building is fairly intact, you might barely be able to tell anything has changed at all, as is the case with La Ruina Habitada by Estudio Jesus Castillo Oli. The architects wanted to it to be an “inhabitable ruin,” giving the long-abandoned structure new life but keeping all the markers of its age.

In Dumfries, Scotland, the ruins of a 17th-century stone farmhouse remain exactly as they were when the clients purchased the property despite the fact that a new house has gone up within the original footprint. Lily Jencks Studio and Nathanael Dorent Architecture took great pains to barely touch a single stone on the farmhouse, building the new modern residence inside and around its walls.

The Dovecote Studio by Haworth Tompkins takes a similar course with a dilapidated brick building on a music campus in Suffolk, matching its hue with Corten steel.

Blending Architectural Styles with Sensitivity

When modern and historic architecture meet, the results can be controversial, but whether or not they’re successful might be subjective anyway. Purists bemoan any alternation whatsoever to a historic structure, hoping ruins can be restored as faithfully as possible, but that approach might not be appropriate for the given project, especially when it’s difficult or downright impossible to perfectly match the original materials. That was the idea behind one of the most divisive restoration projects in modern memory: the Vilhariques Tower and Matrera Castle in Spain.

Before architect Carlos Quevedo began, both structures were little more than a couple crumbled walls at risk of collapse. The Spanish government wanted the ruins to become educational facilities, but we don’t know exactly what these buildings used to look like, so Quevedo simply built new structures into what’s left of the originals, matching their approximate dimensions. Many locals were outraged, comparing the results to the infamously botched restoration of Elias Garcia Martinez’s fresco of Christ known as Ecce Homo.

But what about ruins located in more urban areas, or those that are still actively in use, but in dangerously poor condition? When they’re legally allowed to just demolish the ruins and start over, developers often choose to do just that. It’s a lot cheaper and easier. So it’s nice to see projects like the Kew House by Piercy & Company in London, which preserves an old stone wall to keep a modern home in character with the rest of the historic block.

The church of the Convent de Sant Francesc Santpedor in Spain had plenty of life left in it before architect David Closes was commissioned to convert it into a cultural facility, but it was in a rough state. The adjacent convent had already been demolished in the year 2000. The church wasn’t particularly well built in the first place, so Closes had his work cut out for him making it functional again. He identified its most striking characteristics, like the potential for natural light within its collapsed naves, and used new materials and modern finishes to highlight them. The damage to the church, all of its wounds and scars from over the years, is still visible, and the architect makes no attempt to pretend an intervention hasn’t taken place.

A similar story unfolds at the Vilanova de la Barca Church, which suffered bombings during the Spanish Civil War. Barcelona-based studio AleaOlea tells the story of what happened to the church with contrasting modern elements. The interruption and destruction of the historic building is starkly visible, but the new construction achieves an easy harmony with its monochromatic consistency.

Salvaging & Repurposing Fallen Components

Even when ruins seem too far gone to be preserved, they can remain a part of the landscape, infusing new construction with history and character. Bergmeister Wolf rebuilt a fallen wall and integrated it into a new, modern home that follows the same lines and contours as the original building.

For the magnificent ‘Aloni’ home on the Greek island of Antiparos, a residence straddling a valley, DecaArchitecture disassembled ruinous stone retaining walls on the property and incorporated them into the facade. Built into the hillside, the camouflaged holiday home maintains the look and feel of the land before it was changed and adapted for contemporary usage.

A site of national historical importance in rural China was in danger of disappearing before the studio 3andwich was tasked with transforming it into a tourist destination. The architects turned a collection of small deserted agricultural outbuildings and rubble from a fallen barn into a recreation of Yang’s School, which now serves as a bookstore and museum. This stone rubble forms the first floor of the main building of the new facility, with fresh wooden construction enclosing the second floor and roof.

Whichever road an architect may choose to take, it’s nice to see some elements of history preserved and maintained, creating less waste while establishing a tangible connection between past and present.