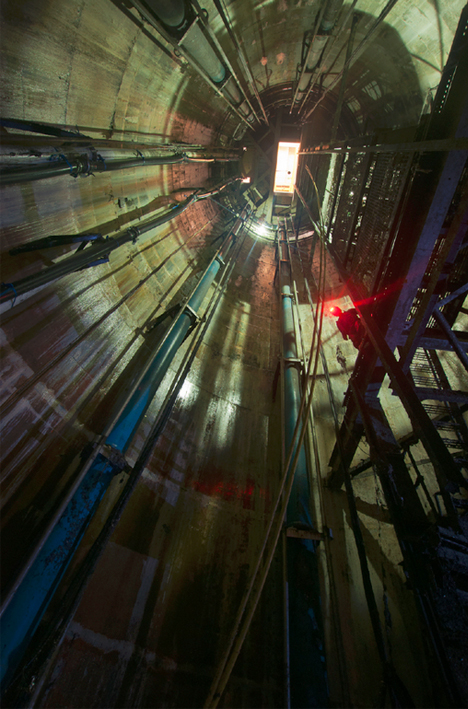

Combining harrowing first-hand experiences, vivid images and historical context, urban explorer and photographer Bradly L. Garrett takes his readers on a stunning in-depth tour through the hidden world of urban exploration and building infiltration. This trip passes through the sewers and subway tunnels of London, over bridges and skyscrapers of New York, and slip you in between derelict buildings and abandoned places around the world.

Explore Everything: Place-Hacking the City (from Verso Books) is more accessible than a manifesto yet more revealing than a manual. In highly readable and engaging prose, it manages to combine personal storytelling and thoughtful reflection with factual urban histories and practical tips for exploring secret spaces.

If you are looking for a coffee-table book of eye candy to flip through, this is not the one for you, but there are plenty of those already. Instead, this is a rarer sort of volume that goes far deeper, drawing on meticulous notes, handmade maps, diligent research and many years of direct experience.

Like something from a China Miéville or Neil Gaiman novel, this author reveals that there truly is a layer of fantastic mystery behind, between or below the surfaces of any city. With stories of personal adventures, from climbing skyscrapers under construction to descending into derelict subway tunnels, Garrett conveys the hot sweat and cold fear experienced in his travels. At the same time, he manages to provide commentary that goes beyond the level of an explorer and into the realm of researcher and philosopher. His combination of first-hand and historical knowledge make this a book worth reading.

The heavy volume may have travel anecdotes and photographs, but it is also not lacking in powerful insights and revealing opinions. Discussing Detroit, Garrett reveals the complexities of a city that is known for its abandonments but is simultaneously in many ways and places a “light, bright, vibrant, beautiful place” that is “full of life, events, politically active citizens, great places to go out” as well as “a plethora of sites ripe for infiltration.” He notes that “as images of decay had become culturally ubiqituitous in this city” many photographers have focused too hard on “sharp, vibrant, long-exposure photography” that produces stylized and idealized imagery that “look uncomfortably similar to traditional photos of colonial explorers, evoking images of white men sticking flags in the soil.” Detroiters sick of their city being seen as a one-sided wasteland will appreciate the author’s even-handed and open-minded approach to and appreciation of their home – and this is just one of many such examples.