In the 1950s, Malcolm McLean developed a modular design that would simplify the loading and offloading of ships, boxing up goods for easier loading and unloading between trains, trucks and boats The standardization of cargo containers revolutionized the modern shipping industry. Today, though, an increasing number of the world’s 20,000,000+ containers are being adapted to new uses, transformed into homes and offices, schools, shops, stages and more.

Proponents of containerized architecture note that the units are generally inexpensive — for many shipping companies, it is easier to sell off unpacked modules than return them to points of origin. Containers are built to be robust and strong, resistant to weather and fire and able to convey heavy loads around the globe. They are also made to be stacked easily on top of one another, which can be useful in creating multistory cargotecture.

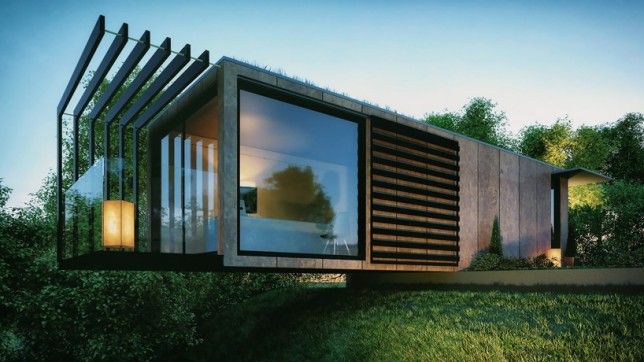

Aesthetically, painted metal containers evoke that ever-popular industrial look a lot of people seek out in converted factories with exposed materials. Container reuse can be sustainable, too, particularly when one considers the energy-intensive process of melting them down for recycling. Some container architecture projects take advantage of the mobile and modular nature of the cargo containers used to build them.

For those inclined toward do-it-yourself approaches, the proliferation of online guides offers a starting point to buying and building container homes. As more individuals and companies engage in creative reuses, standardized methods are evolving, too, for making modifications that meet building codes and streamlining processes like permitting and code compliance, together paving the way for future container-based projects.

Shipping container architecture, however, evokes strong reactions from skeptics as well. “The shipping container is to today’s avant-garde architecture what the pipe railing was to the early International Style,” writes design critic Theodore Grunewald, “an industrial objet trouvé; a totem fetishized more for its aesthetic qualities and poetic and symbolic associations than its practicality.” He cites Dr. Richard Williams, a professor of contemporary visual cultures, whose also has reservations: “They’re great for doing what they were designed to do, which is transporting stuff. A simple technology, they have helped facilitate global trade like no other. But they’re designed for things, not people. Dark, damp and airless, boiling in the summer and freezing in the winter, they’re hopeless living and working spaces.”

There is truth in these criticisms. Without significant modifications for controlling indoor climates, for instance, metal container shells make for poor insulators. In some cases, the answer is to more extensively retrofit them, though of course that adds time, cost and environmental impacts. It is worth keeping in mind that (like any design solution) containers will work (or not work) differently in different places. The standardization of containers and their ability to travel the world doesn’t mean that they provide equal architectural benefits around every port of call.

As with any material or building unit, there are going to be specific project, client and site needs and considerations. Individual containers come in standard sizes, which can be an advantage and a disadvantage depending on the desired program and layout requirements. The world is full of buildings made from unusual materials, including hay bales, tires, soda cans and beer bottles — availability and location play a role in where and how each of these works as well. In places where containers are cheap and the climate is ideal, adaptations can be easier and well worth doing.

A lot of container criticism is also aimed at more pie-in-the-sky ideas, like modular buildings with interchangeable parts. These more ambitious and concept-driven designs, including container skyscrapers and mobile city-to-city apartments, may or may not make it off the drawing board.

On the more practical side, though, ever more companies are evolving repeatable and modular solutions, including materials and methods of insulation, plumbing and electrical wiring specifically designed to work with container structures. Such solutions can make it easier to assemble and outfit cargotecture much more quickly than one might erect a non-prefab alternative. In construction, speed and prefabrication is helpful in reducing energy, time and labor inputs.

Meanwhile, municipal authorities and commercial construction firms recognizing these benefits continue to build large cargo container projects, including emergency shelters as well as group homes, community centers, industrial parks and office complexes. To an extent, the cycle is self-reinforcing as well: as more projects get completed, it becomes easier and more efficient for other container architects and DIY builders to start similar projects of their own.