In Newark, New Jersey, a large and deceptively nondescript building is redefining the Garden State, producing millions of pounds of food per year just outside of Manhattan. This 70,000 square foot facility has the equivalent yield of over 5 million square feet of traditional farmland. Inside, a year-round, closed-loop aeroponics system employs no pesticides and requires 95% less water than field farming. This branch of AeroFarms is not alone — it’s part of a food production revolution with projects ranging from at-home and in-store micro-farms to massive facilities set up in old factories and warehouses around the world.

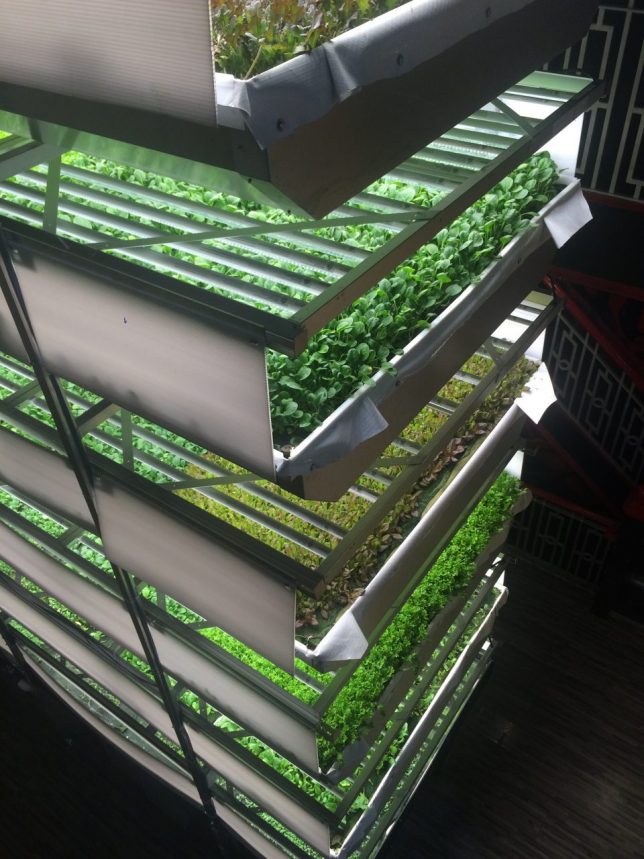

Technically, vertical farming can be done outside, too, by stacking planters in natural sunlight, but indoor vertical farms offer a range of advantages. Inside, there are no seasons and specialized LED lights make it possible to grow plants continuously and cycle through various crops more easily. The controlled environment and standardization of these systems also makes automation easier. In Japan, approaches have gone predictably high-tech, with endeavors like the Vegetable Factory, which is operated entirely by robots.

Spatial containment makes recycling more efficient, mitigates spoilage and reduces the risk of diseases and pests spreading beyond a specific facility. Transportation costs and energy requirements are also reduced for farms that move into old factories and warehouses right in and around cities, putting them closer to consumers. Aeroponics in general also require less material input — mainly mist and air with minimal water and soil — leading to a lighter footprint.

What started in large and independent facilities has begun to spread into mainstream grocery stores and supermarkets, too. A few years back, Target started testing direct retail micro-farms, beginning with leafy greens before moving to tomatoes, peppers and more. Since these kinds of retail spaces are climate-controlled already for the sake of both shoppers and products, less added energy is required to maintain ideal conditions.

In Berlin, a company called INFARM recently partnered with local shops to provide similar in-store services, cutting down on farm-to-table distance right in the heart of a major European metropolis. Meanwhile, in Tokyo, vertical creepers, rice paddies and broccoli fields were integrated into the design of an otherwise Modern-looking office building, brightening up the place while also providing food for the employee cafeteria.

Taking vertical integration a step further, projects like the ReGen Villages aim to incorporate stacked farms directly into residential communities. It may sound impractical or even Utopian, but at its root the idea is relatively traditional: backyard gardens and community gardening are nothing new. Coupled with walkability and density, these kinds of green-centric towns have a lot in common with New Urbanist ideas that go back decades.

Still, it is generally wise to maintain a healthy skepticism when it comes to fresh green architectural trends and technologies and eye-catching renderings. Skyscrapers covered in greenery (or treescrapers), for instance, have proven to be popular but also problematic in practice (catchy conceptual earthscrapers, groundscrapers and sidescrapers, too, for that matter). Sometimes, more practical organic solutions are hiding in plain sight. Take wood, for instance, a historically popular green building material now finding new forms and reaching new heights in tall buildings around the world. Newer is not always better.

Some extreme vertical farming ideas may indeed prove to be far-fetched and unsustainable, but market movements suggest there is a future in these kinds of facilities and approaches. Investors are putting their money where people’s mouths are, buying up disused urban real estate and developing new indoor farming technologies. Already, vertical farming is a $2,000,000,000 industry and experts project it will grow as much as 30% per year over the next decade.

Vertical farms are of course not a complete solution to ongoing threats like climate change and mounting global food crises, but they do show promise — these endeavors are slowly breaking down urban and rural barriers, reconnecting cities with the food sources that sustain them and shortening that critical distance from farm to table.