The word “graffiti” usually conjures images of people with spray cans illegally making murals or jotting down tags using colorful paints. A lot artistic interventions use other tools and materials, though, subverting expectations and working in (literal and legal) gray areas to create works without leaving a conventional trace. Consider, for instance, the massive deep sea monsters, jungle predators and swamp creatures of Russian illustrator Nikita Golubev that lurk in the grimy shadows on the sides and backs of trucks.

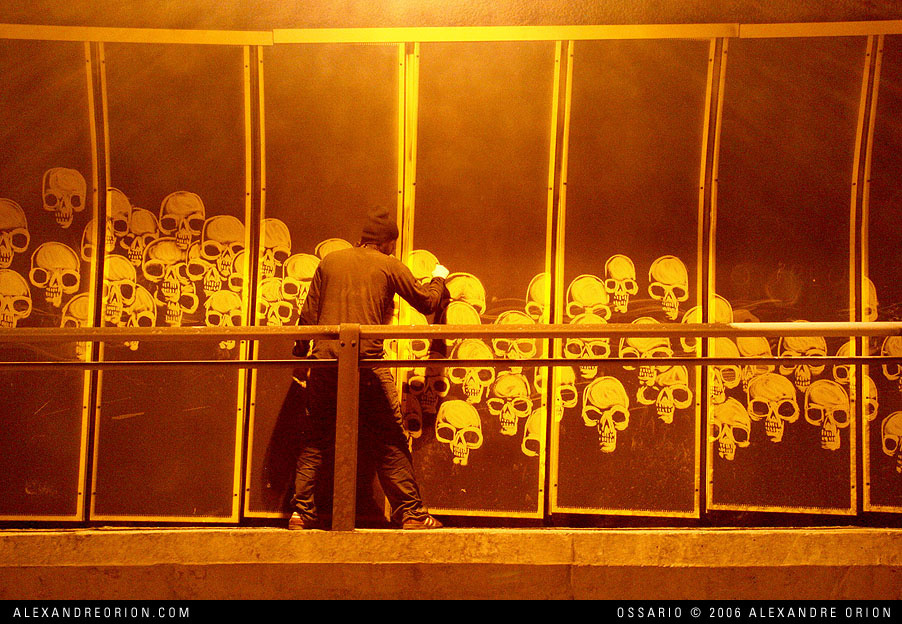

Along similar lines, this series of skulls by artist Orion was made by scrubbing car exhaust from an active tunnel. For those looking to deter street art and artists, subtractive interventions like these can be tricky to pin down. After all, Golubev and Orion are simply cleaning vehicles or public surfaces, albeit very selectively. In many cases, the end result is actually further cleaning — art like this often pushes municipalities to send out teams that then wash off entire areas to make them look consistent again.

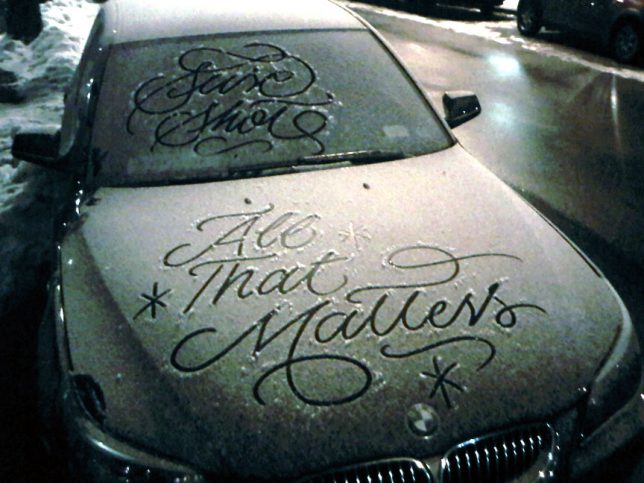

This artistic approach draws different reactions depending on the scale and situation. Take snow calligraphy, for instance — few people seem to mind a nice message traced into the hood of their car. Artist Faust notes that virtually “everyone has an affinity for writing in the snow as a child,” so perhaps it’s also something people feel they can relate to on a more experiential level.

Reverse graffiti not only provokes different response—it also spans a variety of materials and methods and can work with greenery as well as it does with snow or grime. Some moss artists work additively, creating mixtures to apply to surfaces and thus encouraging moss to follow particular grown patterns to produce an specific result. Others, however, actively remove moss to create desired words, patterns and illustrations.

Stefaan de Croock falls into the latter category, using power-washing tools to create cityscapes and other whimsical scenes on surfaces previously covered in layers of moss. As with a lot of reverse graffiti projects, his pieces are generally temporary — the moss simply grows back in to fill the voids over time.

SpY’s work in Besancon, France, combines elements of reverse graffiti and tree sculpting. Turning topiary approaches into a mural-making technique, he shaped vines into a circular work of wall art using an elevated work platform, trimming his way toward a perfect circle.

Light art and projection bombing are even more temporary and generally even less invasive than reverse graffiti. Lighting machines aimed at buildings to create patterns or spell out messages can be targeted and disabled if they persist, but ephemeral light painting like the above work by Lichtfaktor are deployed quickly using glowsticks or other portable devices and have to be captured on camera to work, making them brilliantly elusive.

Meanwhile, if light art is about brief visibility, then hydrophobic spray art is about lasting invisibility. Both are made to be seen and not seen in particular ways, but the latter has a key ingredient that determines when a design or artwork is visible: wetness.

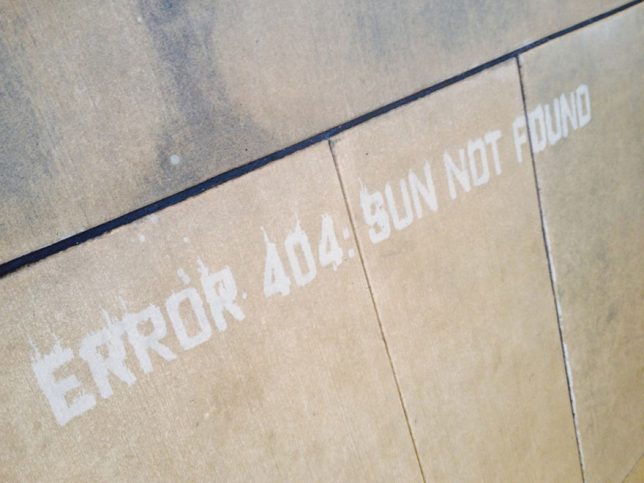

When the hydrophobic NeverWet spray came out, it promised to waterproof everything, but some users found they had mixed results in applying it to things like clothing and touchscreens – it discolored shoes and left a sticky film on devices. Then someone thought to create a stencil and tag sidewalks with the stuff and a new type of visible-when-wet graffiti was born. One can, of course, free-spray with it as well, but stencils help make the outcome more controlled and predictable.

The same basic artistic idea has been applied in other contexts by designers, too — selective hydrophobia can be incorporated into brick pavers or concrete sidewalks, for instance, to create patterns that change with the weather. Clever urbanists might consider ways to integrate useful messages or wayfinding elements into such projects, like arrows pointing to nearest sources of shelter in a storm. Similarly, messages that appear on surfaces that change color with temperature could be used to guide people on particularly hot or cold days.

Practical designs aside, artists continue to experiment outside of traditional material palettes with works that raise questions about visibility and invisibility. There is fun to be found at the intersections of these ideas, embodied in projects like this one by 3D artist Milane Ramsi, who combined different approaches into a single installation — a concrete pillar appears to vanish while simultaneously revealing three-dimensional lettering more reminiscent of conventional graffiti.

Additive or subtractive, vandalism has its grey areas, but what about the seemingly more straightforward removal of graffiti? Here again there are shades of gray. Some artists, like Mathieu Tremblin, paint a surface clean then write over graffiti with their own work — in his case: humorously replacing loose tags with digital-style tag clouds. That, clearly, is of a kind with what was underneath; in places where tagging is illegal, replacement tags are too.

Then there is the saga of the infamous Banksy and the so-called Gray Ghost, an anti-street artist who leaves signature splotches of gray in the wake of his graffiti removals. Some argue the Ghost’s work vandalizes art — others say it is itself art. Legally, like Banksy’s illegal murals, both artists work in a similar space, though in Banksy’s case building owners often go to great lengths to preserve his art, in part for its monetary value.

Exceptions aside, municipal laws are usually clear on painted public art and the goal is generally total graffiti erasure, though it doesn’t always work out that way. This kind of official cleanup usually draws binary responses, viewed by some as a welcome fix and by others as an act of defacement. One award-winning film, however, argues for a third point of view: graffiti removal as the ultimate next step in the progression of modern art. Despite its semi-satirical intent, The Subconscious Art of Graffiti Removal raises provocative questions about what constitutes street artwork in the gray areas of additive and subtractive graffiti.