Before it was abandoned in the wake of the Chernobyl nuclear disaster, Pripyat was a thriving Ukrainian city with a population of nearly 50,000. The relatively sudden exodus of its inhabitants left behind a physical snapshot of the times, preserved by the absence of humans intervention for fear of fallout.

Despite the dangers of returning, urban explorers have been visiting the place for years. Some photographers use cameras mounted on aerial drones to maintain a safer distance. Other in-person visitors less concerned about safety have gone in and looted old buildings. Most, though, go simply to observe, drawn to the deserted city by those mysterious forces that attract people to derelict places — embodied history, transgressive impulses and human curiosity among them.

Such dangerous or hard-to-reach abandoned places can particularly alluring, especially when their stories are compelling. Take Hashima, just one of many Japanese islands but unusually packed with old buildings. A thriving coal-mining city in times past, “Battleship Island” once had the highest population density on planet — until a drop in coal production led to its desertion. In recent years, more and more photos and videos of the place have proliferated thanks to the internet, in turn raising questions about how much to repair, restore or change it in order to make it more accessible for an increasing number of people visiting by boat.

While some architectural artifacts in remote locations like this have been left largely alone by visitors or modified simply to accommodate tourists, others have gone through generations of much more radical change. Off the coast of Great Britain, army and navy sea forts have been turned into everything from private retreats and luxury resorts to pirate radio stations and rogue micro-nations. Here, a combination of factors, including abandonment by the government and somewhat more accessible (yet still aquatic) locations have conspired to make these structures more appealing for different kinds of adaptive reuse.

Preservation, Restoration & Contention

In central locations with more people (and thus opinions) the fate of historical places has often been the subject of controversy. In many cities, preservation of a current state tends to win out. Even such a seemingly neutral position can be contentious, though, particularly when efforts to preserve are partial or seem superficial, as in the case of ‘ghost facades‘ where only thin surfaces are saved.

Rote historicism is a simplistic default that can lead to strange and unexpected results and extreme scenarios, like cities demolishing entire buildings to “preserve” the appearance of historical skylines.

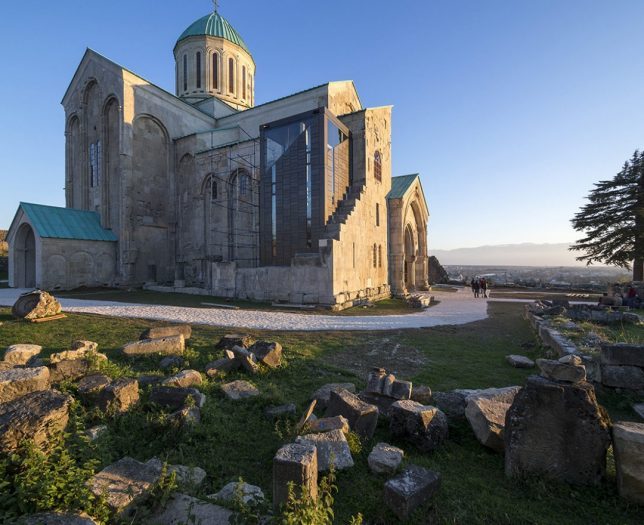

In other cases, restorations are pursued, though choosing a target point of time or period can be fraught — some buildings have been changed substantially over centuries, making it challenging to decide what aspects to restore. Either way, renovations involve modifications, which can quickly divide people who crave a kind of physical authenticity from those who embrace the notion that architecture necessarily changes over time — the situation of Notre Dame after the fire illustrates the point. Supporters of extensions and additions that don’t match the original argue that visible differences will help people in the future understand what is truly old and new, while critics note that most famous old structures have already been damaged, rebuilt and changed for centuries. There is no single solution.

Ruination, Rediscovery & Reclamation

There are people, too, who think that historical ruins should simply be left alone to decay. Along those lines, many building infiltrators and urban explorers in the United States, Europe, Asia and other parts of the world where urbex is popular follow an unwritten code to leave no trace of their presence, allowing subsequent visitors to experience a disused space as they did. There is beauty in glimpsing snapshots of history and watching nature slowly reclaim a structure.

Some abandoned places endure through careful consideration and the avoidance of further damage, but many persist in their current form simply because they are less accessible in the first place — the latter status applies to many underwater towns and archaeological sites as well as underground tunnels, crypts and caverns.

Once rediscovered, though, the fates of such places depend on where they are located and current attitudes toward ruination, preservation and restoration, which continue to change over time, much like the locations in question will do … with or without further human intervention.